After 16 years of BC Liberal reign ended in 2017, all eyes were on the NDP minority government’s efforts to cool British Columbia’s hot housing market.

In 2018, the new government introduced a higher property tax rate for properties over $3 million, dubbed the “school tax,” as the money funds schools.

It also brought in the speculation and vacancy tax, which targets secondary residences and property owned by foreigners. Set at $20 per $1,000 of assessed value, the tax only applies to properties in a number of urban markets.

On Vancouver’s west side, angry homeowners rallied to protest the school tax “tax grab.” The vacancy tax was called “stupid” by former BC Green leader Andrew Weaver.

Despite the outcry from some quarters, the measures proved to be popular among British Columbians of all political stripes.

But did they work?

“We still have a housing crisis,” said Andy Yan, the director of Simon Fraser University’s City Program. “But they did stabilize it.”

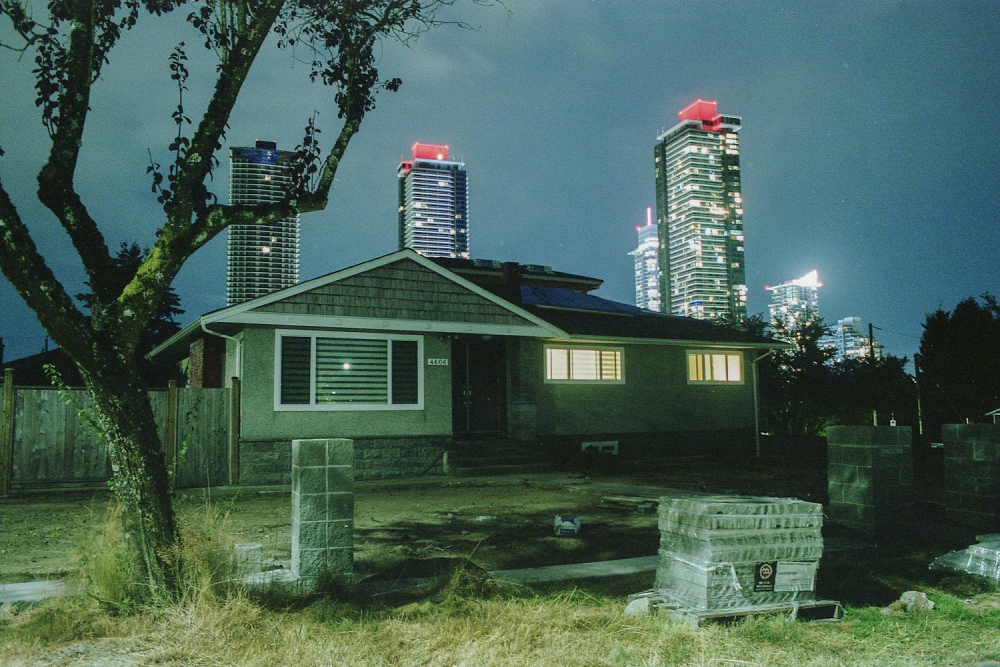

Affordability was a top issue in the 2017 provincial election. In Metro Vancouver, the epicentre of the crisis, the average price of a coveted detached house soared to $1.47 million from $217,400 during the Liberals’ time in government from 2001 to 2016.

But housing isn’t just about houses, NDP Leader John Horgan reminded viewers during this election’s only in-person debate. It exists on a “continuum,” he said.

Yan noted the private housing market can’t serve all needs, and if governments neglect parts of the continuum that need assistance, there will be a “backlog” like we’re seeing right now.

He points to a 2018 count of homeless people in B.C. that found that 18 per cent had formal employment, with another 29 per cent either informally employed or self-employed.

“It shows you the dysfunction of the housing system in B.C.,” said Yan, adding that 47 per cent of unhoused people in the province do some kind of work, and that tent cities are a symptom of this dysfunction.

Federal involvement in affordable housing plummeted in 1993, when Paul Martin’s austere Liberals cancelled all spending on new homes. Until that point, B.C. had partnered with the federal government to build between 1,000 and 1,500 units of social housing a year, up to 2,000 if you include co-op homes.

But after the 1993 cuts most provinces followed the federal lead and abandoned the social housing file. B.C.’s NDP government in the 1990s was a rare exception, funding at least 600 units a year.

When the BC Liberals were elected in 2001, they purchased and renovated some single-room occupancies but did not keep up with the creation of new social housing.

Near the end of their time in power, they rolled out a controversial plan to sell $500 million worth of province-owned social housing to fund the construction of new social housing and the expansion of rental assistance programs.

While the properties were sold to non-profit housing providers, the Liberal government planned to pay them $30 million a year for 35 years, totalling $1 billion, to help with the mortgages. The program was questioned by the auditor general in 2017, who said that the province did not prove how it “provides value for money.”

This was the situation the NDP inherited when it took power in 2017.

Alongside the popular market cooling measures, their government began creating affordable housing again through funding and partnerships.

In the past three years, 3,070 homes for homeless people were built or are underway. This includes the modular supportive housing that has popped up in various cities.

There are also 9,840 homes built or underway for people who make up to $74,000 a year, and another 2,800 for middle-income earners who make up to $99,000. Portions of funding cater to specific groups, such as housing providers that serve Indigenous people or women with children who are at risk of or have experienced violence.

CEO Jill Atkey of the BC Non-Profit Housing Association says there’s no question that these investments are “historic.”

By B.C. standards — and that of other provinces as well as the federal government — the funding is impressive, she said.

The province is “actually outspending by a significant amount any sort of federal investment,” added Atkey, whose organization represents over 800 non-profit housing providers.

However, the housing backlog that Yan spoke of has not yet been cleared.

“The frustrating thing with housing is that you can’t develop a very elastic response,” said Atkey. “So, when a crisis hits, you can’t build housing and fix that housing immediately. It takes time. You got to identify the land, secure your funding sources, and got through municipal approval processes... it’s not possible to turn the corner on the crisis overnight.”

Atkey shared an alarming ratio that speaks to the rapid pace of affordable housing being lost. In B.C., for every unit created that can rent for less than $750, three are destroyed.

But on a national level, that ratio is one affordable unit created for every 15 lost.

“This speaks volumes about our investment,” said Atkey, “but we’re still in a situation where we need stopgaps.”

This election, the NDP is campaigning on continuing its 10-year plan of funding and partnerships for affordable non-market housing.

Elsewhere along the housing spectrum, some tenants are less pleased with the NDP. This is despite the party addressing some problems brought up during the last election.

Under the NDP government, landlords are no longer allowed to increase rent beyond the allowable annual increase by signing a new contract with the same tenant when the old one expires.

Landlords are also no longer able to justify dramatic rent increases if nearby rents soar.

The NDP also introduced new policies for renters who are evicted when their building is redeveloped. The government mandated that the displaced renters get first dibs on the new units, but there is no requirement for landlords to offer them at their previous rents. (The City of Vancouver is currently looking into retaining affordability for new units using its own powers.)

Spokesperson Mazdak Gharibnavaz of the Vancouver Tenants Union says most critically, the party has not implemented “real rent control.”

The NDP did lower annual rent increases to the rate of inflation (previously, it was inflation plus two per cent), but he says that this doesn’t address the problem that once a tenant moves out of a unit, a landlord can raise the rent to whatever they like.

What the union wants is vacancy control, which would tie rents to the units themselves.

While landlords would argue that the current situation allows them to collect rent at fair market rates, Gharibnavaz said that it “financially incentivizes evictions” as a way of dodging rent control.

“Landlords can figure out one reason or another to evict you, and then in between tenancies, jack up the rent,” he said. “This is the number one thing that destabilizes rents and causes them to be sky high.”

The tenants group said that the NDP’s bias toward the interests of landlords was also apparent when COVID-19 arrived. The government banned evictions for non-payment of rent during the pandemic, but only until September, and renters must repay what they owe by July 2021.

The decision alarmed Gharibnavaz.

“I can’t fathom Housing Minister Selina Robinson saying, ‘Yes, this is a good idea. I want people to start getting evicted again. I don’t care if they get infected or if something happens to them.’”

Gharibnavaz said this provides a window into NDP thinking.

“When we talk about who we need to protect during a crisis, that has to be the most vulnerable in society, not people who have a profit motive,” he said. “This is essentially saying that landlording is an industry that needs to come out of this crisis completely untouched. The air travel industry is underwater. Tourism is shutting down.... [For landlords], this is a risk they took getting into the business.”

In the NDP’s platform for renters, the party promises to freeze rents until the end of 2021.

“That’s a good start, but we’ve been asking that for years,” said Gharibnavaz.

It’s not just Horgan’s New Democrats that have taken note that housing is a continuum.

The Greens’ platform addresses everything from co-ops to acquiring old rental buildings to the “financialization of the rental market.”

Even the BC Liberals have taken note, a departure from their focus last election on individual ownership.

In 2017, they pledged to ensure that “dream of homeownership remains within reach for the middle class.” They campaigned on offering loans for down payments and reducing taxes for first-time buyers, homeowners’ principal residences, the purchase of new homes and homeowners looking to add rental suites.

But the BC Liberals have suffered from the appearance that they were too closely entwined with the development industry as housing costs in the province soared during their years in power.

Real estate marketer Bob Rennie, also known as the “condo king,” served as the BC Liberals’ chief fundraiser at one point, and many of the party’s largest donations were received from developers.

As then-party leader Christy Clark downplayed the impact of foreign money on local housing, she met potential East Asian property investors, telling them about being “proud of our record of opening doors to investment.”

The party’s late introduction of a foreign buyers’ tax in 2016 was not enough to secure power in the 2017 election.

This time around, the BC Liberals have a chapter on both homebuyers and renters in the platform — one way of remedying Leader Andrew Wilkinson’s controversial comments in 2019 that renting was a “fun” and “wacky time of life” — including a number of promises to help incentivize and speed up the construction of affordable housing.

It’s very much focused on housing supply as a solution. Wilkinson pushed that further by accusing Horgan in the recent debate of creating a “tight market” that lags behind on creating units for the thousands of people moving to the province each year.

But SFU’s Yan decided to investigate and found that more units in the private market were built during the BC NDP’s term than the Liberals in their final years.

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. data shows that 69,400 houses, condos and rentals were built during the Liberal years of 2015 and 2016, while 81,650 were built during the NDP years of 2018 and 2019.

Overall, there’s a smorgasbord of housing solutions in the party platforms for voters to investigate — everything from revamping tax structures to parking requirements for certain developments — but a smorgasbord is what it’ll take to fix this problem after the federal Liberals dumped the provision of social housing in 1993.

Subsequent governments on all three levels were left confused about housing responsibility. Larger municipalities such as Vancouver and Toronto have tried incentivizing the private market to help out.

As for a successful fix for housing in province, Yan said the government will have to address all needs along the housing continuum: both market and non-market housing, both renters and owners and both lack of affordable supply and unhealthy demand. ![]()

Read more: BC Election 2020, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: