The air, a quiet hum of bird calls and rippling waves, is suddenly full. Like thunder, the clap of a humpback whale breach takes a moment to travel to you, just slightly out of sync with the instant the 30-tonne mammal hits the surface of the sea. If you respond quickly enough, you can see the giant falling back into the churned water. At my dad’s house on Saturna Island, the southernmost of the Gulf Islands, we keep the sliding door open all summer so we can hear the cannon-fire sounds of breaching — and maybe catch a glimpse.

This year Heather, a humpback whale who frequents the waters around Saturna in the summer, returned to the island. A new calf, Neowise, at her side.

Neowise was born somewhere near Hawaii or Mexico this winter. His tail fluke is spotted with white, mirroring his namesake, the comet that hung over the Salish Sea this summer. He is pure energy. While Heather’s back peeks out of the water, Neowise flings himself up and out, breaching over and over. I spent all of June watching them, this mother-son pair passing by my house every day; a feeling of hope in a cruel summer.

I started to think of Heather and her new son as my neighbours. They were the subject of island gossip — via email chains and Facebook posts, conversations at the General Store. And yet, I realized I didn’t know anything about this recent mother. Where is she from? How old is she? How does she fill her days? What dangers to her well-being lurk, and what are the chances we will remain neighbours in years to come?

On a sunny Friday afternoon, the last day of July, I walked down to the water to talk to Lucy Quayle, a master’s student who spent the summer doing marine mammal observation on Saturna. The sky was deceptively blue but the wind beat across Boundary Pass, and Lucy was bundled up in a sweater, watching the water from under a sturdy beach umbrella. I sat down in a folding chair beside her, staring out at the empty surf. Heather and Neowise had moved up to Galiano in the middle of July, and without their constant appearances the days passed with less excitement.

Lucy had originally planned to study the endangered Southern resident killer whales, but on her second day on Saturna she saw Heather and Neowise for the first time and became fascinated. She saw the humpback pair 15 out of the 24 days she worked in June. “It felt like you could see the calf learning different things,” she told me. “Sometimes they’d split up and the calf would be rolling around or flapping a lot, and Heather had already tried to go one direction and then she’d have to come back to try to pick him up and then they’d continue on.” One day, Lucy counted the calf breaching more than 60 times.

It was Lucy who took the photos that identified Neowise as a male, and who has captured the first clear images of his tail fluke, the most distinct part of the whale that is used for identification.

I wanted to find out more about Heather’s history, and Lucy urged me to speak with Tasli Shaw, a naturalist who runs the Humpback Whales of the Salish Sea catalogue, and who gave Neowise his nickname (generally speaking, whoever photographs the whale first is often given the opportunity to name the whale, based on unique markings on their tail fluke or dorsal fin). When I reached out to Tasli, she said: “I am always happy to talk humpbacks!”

And it’s true. She bubbles over with passion for the whales — knows their names, their flukes, their stories. She tells me Heather’s:

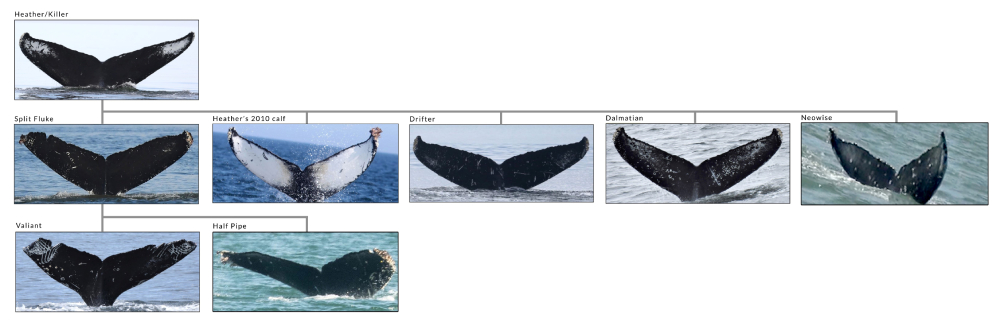

Heather was first spotted near Race Rocks in the early 2000s by Tasli’s colleague Mark Malleson. He took the first photos of Heather and saw that her tail fluke had a little “H” on it, leading him to give her the nickname “Heather.” At the time, Heather was already close to being an adult, and in 2006 she returned with her first known calf, Split Fluke. If that really was her first offspring, Tasli explained to me that Heather would have been about seven-to-12-years-old at the time.

When Split Fluke was spotted in the Salish Sea she had rake marks on her tail, indicating she had been attacked by killer whales on her northbound migration. Heather, it seems, was able to fight off the killer whales and save her calf. In 2017, she became a grandmother for the first time when Split Fluke brought her new calf, Valiant, to the Salish Sea. But Valiant had rake marks as well. “Split Fluke maybe remembered what happened to her when she was a calf and saw Heather fending off the killer whales and Split Fluke managed to protect her baby as well,” Tasli speculated.

Unlike orcas, humpback whales do not travel in family groups. After migrating south later this year, Neowise will leave Heather’s side and they will likely never associate together again. In her calf-less summers, Heather is known to spend her time with another female humpback named Raptor. Last summer, the pair swam from Saturna to the northern tip of Vancouver Island and back. This year, Raptor was spotted in the Salish Sea with a calf as well, meaning she and Heather would have both been pregnant during their trip together. With Neowise born this year, Heather is now a mother of five and a two-time grandmother.

“We can only assume that in historic times, before records were kept, there were whales everywhere, and we only need to talk to our great-grandparents to hear this story,” Ernest Alfred, a traditional leader from the 'Na̱mgis Nation, told me. “Our people have direct connection, specifically with the humpback and the killer whale. Those connections go deep within the land, deep within the ocean, with everything that lives in the entire ecosystem, the air, land, water, everything.”

“That’s an ancestor of ours,” he explained. “The humpback, the killer whale, all of these marine mammals have incredible importance to us and our heritage.”

Gwa’yam is the Kwakwala word for whale, and Ernest told me nations and families wear gwa’yam crests to identify them as descendants. “There’s many, many stories, there’s far too many stories to start rattling off, and there’s not one more that’s more important than the other,” he said. “These are claims made by nations; claims made by specific families who have a story that tells why we wear that particular symbol.”

But, in the early 1900s, commercial whaling off the province’s coast decimated the humpback population, practically extirpating them from this area. When an international moratorium on humpback whale hunting was passed in 1966, the population’s slow recovery began.

Jackie Hildering, co-founder of the Marine Education and Research Society based on northern Vancouver Island, was working as a naturalist on board whale watching boats when the humpbacks started to return. In 2003, MERS observed only seven humpbacks in their study area; last year they recorded 97. “It just wasn’t acceptable to not know who those whales were and what they might be showing us about the ecosystem,” she said.

Like Jackie, Tasli was inspired to start cataloguing the humpbacks when she watched their return. “Around 2013 or so, there was a noticeable influx of humpback whales into the Strait of Georgia, which is where I spend most of my time,” she told me. “And with so much fanaticism around the killer whales, I was perplexed to realize that no one I asked really seemed to know much about the humpback whales that were visiting our waters. At that point only one or two of the humpback whales had nicknames, Heather included, but the rest were a big question mark.”

Since 1997, Tasli and Mark have catalogued 601 individual humpbacks in the Salish Sea, a third of whom are repeat visitors to the area.

Cataloguing the whales is no small feat. Until 2010, Fisheries and Oceans Canada maintained a province-wide Humpback Whale Catalogue. In 2011, these whales, classified as the “North Pacific Population” were down-listed from a “threatened” population to being of “special concern.” Since 2010, the cataloguing effort has been maintained by organizations like MERS, the North Coast Cetacean Society, and Humpback Whales of the Salish Sea. They, and other collaborators, are currently working to update the province-wide catalogue.

Along with collecting their own data, humpback-devotees like Tasli pour over photographs of tail flukes and dorsal fins, trying to identify whales spotted by whale watching boats and photographers on land. “It takes an incredibly large community to study giants,” Jackie told me.

Have you ever stopped to wonder if the chickadee singing in your backyard is the same one you saw yesterday? Questioned if the deer trying to eat your flowers is the young fawn you remember fondly from two years ago? Like toddlers who have yet to learn object permanence, we often fail to realize that the animals around us — from ants to fish to whales — have lives that unfold while we aren’t watching.

The efforts to catalogue these whales push back against our human tendency to see animals as fleetingly random. “If you don’t know who individual animals are, you can’t count them, you can’t learn about interactions, you can’t learn about life history,” Jackie said. And because of how many whales were lost to the whaling industry, there is still so much we don’t know about humpbacks — what their average lifespan is, how often they have calves, and how they socialize.

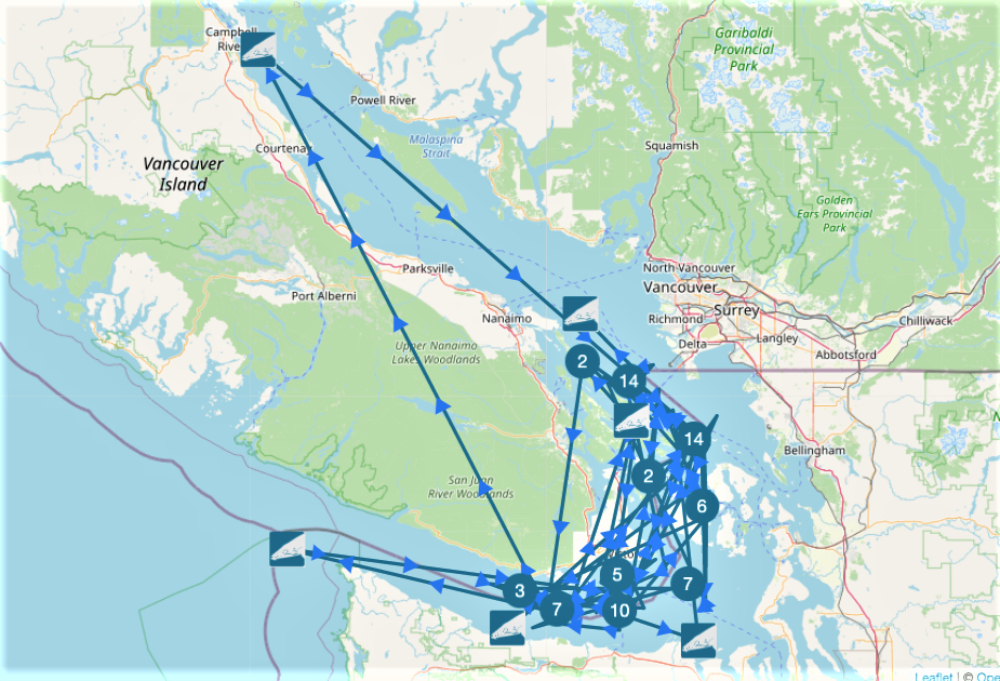

Happywhale, a website where anyone can send in their whale photos to be identified, allows you to search by individual. Type in Heather’s name and you will see a map of where Heather has been spotted.

What stands out when I look at Heather’s map is how small it is; Heather clearly loves these waters. Jackie told me that this kind of attachment to place is common with humpbacks — “These are fishermen and fisherwomen who have preferences for certain places on our coast,” she said.

The co-founder of Happywhale, Ted Cheeseman, explained that his website uses an algorithm to identify whales from their tail flukes, allowing anyone to keep track of the individuals they’ve spotted. “The more people are engaged, the better the scientific value of what they can contribute,” he said. “One of the great frontiers, especially in marine mammal science, is recognizing that there’s so much culture in these animals and there’s individualism in that culture and quite a lot of diversity.”

On July 6, a young humpback was struck by a ferry near Seattle. A video taken by a naturalist on a nearby whale watching boat showed the humpback staggering before disappearing beneath the waves. When I watched the video my heart leapt into my throat; the risks that humpbacks face are much harder to ignore when a neighbour is in danger. Heather and Neowise hadn’t been spotted in a few days, and the thought that Neowise could be wounded or worse pressed on me. Finally, we found out that Neowise was safe. Still, the actual victim had a name and a story. Chip was a young whale, born in 2017. Tasli teamed up with others to work around the clock to identify Chip and learn what they could of his fate.

When Chip was hit there was no blood in the water, no body. There is a misconception that dead whales will always wash up onto shore, their carcasses sending a message of human hubris. But in the vast majority of cases, their bodies sink. For humpbacks, who do not have biosonar like killer whales do and who often move in unpredictable ways, the threat of ship strikes is a constant danger — to both whales and boaters.

Chip has never been seen again, and is presumed to have died.

Another very real risk to the humpbacks is entanglement in fishing gear, which can cause infection and prevent whales from being able to feed or move properly. It is an excruciating way to die.

MERS research, conducted in collaboration with DFO, reveals that approximately 50 per cent of the humpbacks off the coast of B.C. have entanglement scarring. There are currently four known entangled whales somewhere off our coast, and knowing their identities is vital to finding and saving them. “If you’re looking for someone, you have to know what they look like and you have to know where they are more likely to go,” Jackie said.

Heather herself is a survivor — when she and Raptor took their trip to northern Vancouver Island, she was spotted by MERS with fishing gear on her tail fluke. They weren’t able to perform a rescue and Heather disappeared. Luckily she was spotted a few days later, having managed to shed the gear on her own.

“She’s chosen a fairly difficult habitat to exist in in the summer; this urbanized waterway that’s used as a highway for global shipping and recreational boaters and fishing and tourism of all different descriptions,” Tasli told me. “Yet here she is with a couple kids under her belt and two grandkids. She’s quite inspiring.”

Where Heather goes when she’s not in B.C. is still a mystery. Because Happywhale has collected so much data from Hawaii and mainland Mexico but has yet to find Heather, Ted speculated that she might go to the breeding grounds in the islands off of Mexico, where Happywhale doesn’t have many photos. Both Heather’s daughter Split Fluke and grandchild Valiant have been matched to Mexico, and evidence suggests calves return to the breeding grounds where they were born.

Next summer, like those past, we will wait for Heather — and now, perhaps, Neowise — to return.

There is reason to believe we’ll remain neighbours for years to come. “There is a rebound,” Ernest told me. “We’ve seen the whales return to this area because it’s rich, because it’s plentiful.”

“But it’s been suppressed,” he added, reminding me of the human activity that increasingly threatens humpbacks in B.C. waters. With infrastructure projects like the Trans Mountain Expansion project and Roberts Bank Terminal 2 project set to increase shipping traffic in the Salish Sea, I wonder, will Heather live to be a great-grandmother? Will Neowise survive? Or will he disappear to the ocean floor like so many humpbacks?

Like me, Heather and Neowise spend their summers in the Gulf Islands. I know their stories — and worry about how they might end. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: