The shock to Canada’s economy by the coronavirus arrived at a critical moment for the planet. The next six months, warns the International Energy Agency, will be pivotal to avoiding nightmare outcomes on climate change.

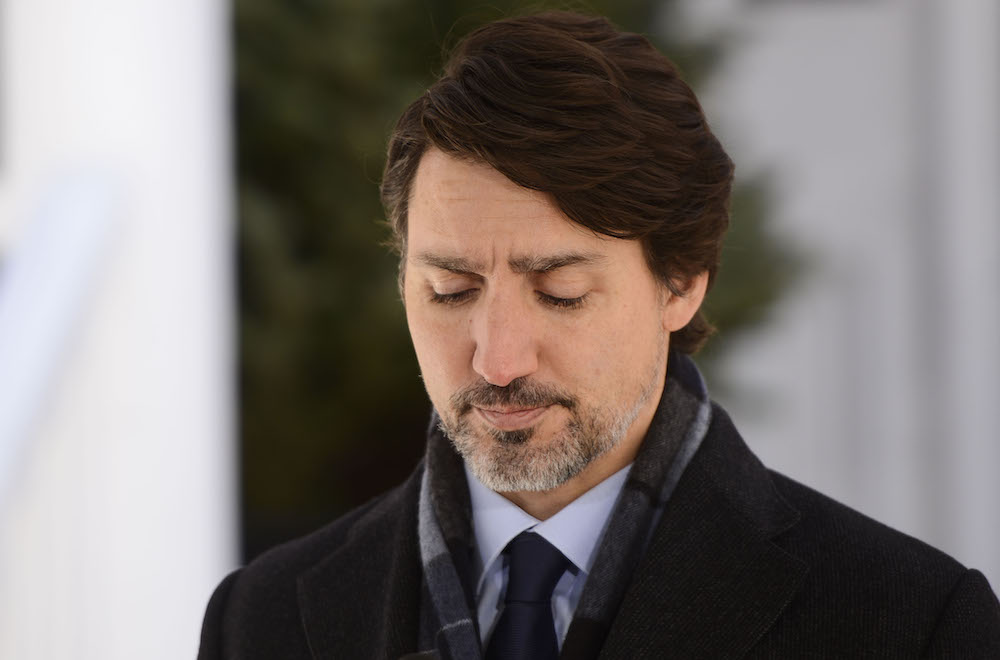

Will the Trudeau government, as it pours billions into a recovery plan still taking shape, shift one of the world’s most emissions-intensive societies towards a greener economy? Climate advocates say that question should be top of mind for Canadians, and they say time is running out for a hopeful answer.

Since late April, the federal government had been asking for advice on how to recover from a lockdown that’s caused millions of job losses while potentially knocking 12 per cent off the country’s GDP. But as a June 19 deadline for public submissions approached, activist groups like 350 Canada argued that “most of the submissions are coming from fossil fuel companies, banks and corporations who only care about protecting their bottom line.”

350 urged its supporters to digitally flood the submissions process. Demand that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau lead an economic recovery guided by the increasingly dire warnings of climate scientists, the group said, as well as the human rights of Indigenous peoples.

“So many people spoke up that the government’s online consultation portal temporarily crashed from the traffic,” 350 wrote in an email to its mailing list shortly after the process closed.

Groups like 350 sense opportunity in the broader political moment. Global protests caused by the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis have heightened public awareness of deep social inequalities at the same time that the Trudeau government has spent $250 billion on emergency coronavirus relief and assigned three cabinet ministers to craft an emissions-reducing recovery.

When climate advocates proposed an economy-shifting Leap Manifesto back in 2016, it was scoffed at by then-NDP Alberta premier Rachel Notley as “naive” and dismissed as “a prescription for economic ruin” in the Globe and Mail.

Four years later, with the European Union moving forward with a proposed green recovery worth $800 billion and U.S. Democratic candidate Joe Biden floating the idea of spending trillions of dollars on a green stimulus targeted in part to communities of colour, the politics of massive government-led investment programs to address climate change and its inequities have shifted profoundly — at least for now.

“Things we were told aren’t possible for a very long time are actually possible once they’re prioritized,” said Amara Possian, a Toronto-based campaigner with 350. “In this moment where the cracks are exposed, it’s clear that our economy can’t meet the needs of people and the planet. And it’s also clear that everything’s on the table, people are ready to dream and to fight and make sure we aren’t going back to a deadly and destructive normal.”

In addition to cutting Canada’s economic dependence on industries that disrupt and destroy planet-stabilizing ecosystems, this type of recovery could mean giving “Indigenous folks more resources to be able to better manage the areas that they’ve already lived in for generations,” said Lindsey Bacigal, a spokesperson for the organization Indigenous Climate Action.

Hundreds of civil society groups support calls by 350 and Indigenous Climate Action for a “Just Recovery” in Canada.

These demands, radical though they may seem to some politicians, are increasingly aligned with mainstream financial realities. The business case for oil, whose price briefly went into the negatives this spring, is at risk of tanking as low-carbon alternatives accelerate. The macroeconomic trend is so apparent that industry outlets such as OilPrice are now predicting 2021 will be “the year of renewable energy” while oilsands giant Suncor explores a future where bitumen is no longer used to produce gasoline and diesel.

Corporate Knights, a Canadian media outlet and research company that describes itself as “the voice of clean capitalism,” calculates that if the federal government spends roughly $10 billion per year over the next decade on green industries, money it could find by closing unproductive corporate tax loopholes, it would catalyze $681 billion in private sector investment and potentially create double the jobs lost in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s the first time in our lives that all the standard operating procedures have been thrown out,” said Toby Heaps, the organization’s CEO and co-founder. “That never happens. There’s a window open, and the question is, are we going to go through it?”

Though the global shift away from fossil fuels is rapidly gaining momentum, oil and gas producers, along with their powerful financial allies, still wield huge political influence in Canada. Trudeau’s efforts to reconcile these two realities — show the world he’s serious about fighting climate change while also protecting an entrenched national industry — have resulted to date in garbled coronavirus relief policies.

Oil and gas producers currently can apply to a $550 million loan fund to help them prevent methane leaks. Yet at the same time, those oil and gas producers’ methane emissions are exempt from the Canadian carbon tax. To access another pool of loans, companies have to disclose data on their climate impacts even as the federal government has no mechanism to enforce it.

“As always,” reports Politico, “there’s a catch.”

Because of his competing priorities, it’s uncertain how committed Trudeau is to a transformative “green recovery.”

In May, the prime minister said “there is a need for clear leadership and clear targets to reach on fighting climate change to draw on global capital.” But a week later the Globe and Mail reported he was seeking recovery advice from the heads of Canada’s big banks, who in addition to being proponents of renewable energy are outspoken defenders of oil and gas expansion.

Heaps worries that favorable economics for green industries won’t alone result in recovery policies that align Canada’s economy with the urgent actions necessary to stabilize global temperature rise. He thinks massive and sustained public pressure is crucial: “If millions of people don’t call for it, I think there’s a big risk we miss this opportunity.” The “Just Recovery” proposal, backed by more than 400 organizations, calls for prioritizing fighting climate change, mending the social safety net and recognizing the rights of Indigenous peoples. Supporters include physicians, disability advocates, labour unions and environmental groups.

“There’s a ton of potential public support right now,” Possian said. “Our job as organizers and activists is to figure out how to activate that. There’s the challenge because of the pandemic of figuring out how to reach people when traditional face-to-face organizing methods aren’t on the table.”

350 is organizing digital rallies at the moment. In the fall there is potential for young school strikers associated with Greta Thunberg to refuse to return to classes. If lockdown restrictions continue to lift there could be large in-person protests.

What activists are demanding makes sense to a range of financiers and economists, researchers in the U.K and the U.S. have found. Earlier this year they surveyed 231 central bank officials and other economic experts and identified coronavirus stimulus policies that could “deliver large economic multipliers, reasonably quickly, and shift our emissions trajectory towards net zero.” Investing $1 million in fossil fuels creates on average 2.65 jobs, according to one study cited in their paper, but more than seven jobs if it’s invested in greener industries.

In Canada’s fossil fuel industry, even if production continues to increase, jobs are projected to decline steeply. As private capital investment in the oil patch fast recedes, bitumen producers are pursuing driverless trucks and other technologies that shrink their workforces.

Climate advocates urge the government, therefore, spend its recovery dollars in ways likely to produce lasting jobs. Aggressive federal investments in energy efficiency — which requires an army of workers across the country to install heat pumps, seal off cracks, improve ventilation and do other things that reduce a building’s energy usage — could put “220,000 Canadians to work over the next 12 months,” according to Corporate Knights.

That in turn could reduce Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions by 22 megatons, which would be comparable to taking every vehicle off the road in B.C.

There are potentially social benefits as well. Research suggests that economic spinoffs are highest when energy efficiency programs, which result in reduced energy bills, are crafted specifically for low- and moderate-income households. “For the working poor and seniors in particular… the stimulus benefits are much better, because those households are more likely to spend the money they save in the local economy,” said Brendan Haley, policy director of the group Efficiency Canada.

Such programs might not be of much use to Indigenous people, however, unless they include federal actions to solve a severe housing crisis in Canada’s North, address the 75 per cent of reserves with contaminated water and provide safe housing for vulnerable Indigenous women who are at much greater risk of going missing or being murdered.

“A lot of Indigenous folks aren’t even at the point of talking about retrofitting or making houses greener because these folks don’t even have access to adequate housing to begin with,” Bacigal said.

This is an example of why First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities need to be part of the recovery talks from the very start, she said. “I don’t think a recovery could be called ‘just’ if it goes forward without adequate representation of Indigenous peoples.”

The pandemic has heightened recognition, even among Canada’s conventional business powerbrokers, that the current system needs to change in order to stave off political and economic upheaval down the road.

In early June, the CEO of Suncor, Mark Little, wrote in Corporate Knights that the “temporary economic lockdown triggered by the 2020 pandemic is giving us a glimpse into a not-too-distant future where the transformation of our energy system could disrupt demand on a similar scale.”

Little and his co-author Laura Kilcrease, head of the provincial research and development corporation Alberta Innovates, linked to a report from the French banking giant BNP Paribas arguing “that the economics of oil for gasoline and diesel vehicles versus wind- and solar-powered [electric vehicles] are now in relentless and irreversible decline.”

Kilcrease thinks Canadians need to take those projections seriously. “Even if you believe the [oilsands] industry is 30, 40 or 50 years off from being no longer needed in the way it is today, that’s really a blink in the eye when you start to think about the transformation of such a large industry,” she said.

Alberta Innovates is studying what would happen if bitumen were used to produce things like carbon fibre, a valuable lightweight material that can be used in electric vehicle manufacturing, instead of gasoline and diesel. Revenues from the oilsands, it predicts, could potentially quadruple. “Just by diverting 852,000 barrels a day into carbon fibre… you’re actually going to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 126 megatons a year, that is ginormous,” she said.

That would be welcome news for the global climate, but it wouldn’t necessarily change the “overwhelming” environmental disruptions faced by people in the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation and other communities adjacent to the industry’s strip mines and toxic tailings ponds. “I feel like anything based on extraction is inherently against Indigenous sovereignty,” Bacigal said.

Difficult questions also arise when thinking about how to transition Canada’s energy supply to 100 per cent fossil-free sources. Expanding the hydropower that already supplies 90 per cent of the country’s electricity can disrupt ecosystems necessary for the survival of Inuit communities. Building wind turbines across the southern prairies and connecting them to an interprovincial clean energy grid, as some green recovery proponents suggest, won’t necessarily replace the stable and well-paid union jobs lost during the phase-out of coal.

“Operating wind facilities doesn’t take a lot of people,” said Brett Dolter, an assistant professor at the University of Regina who studies clean energy. “It’s a different [employment] model and that’s a potential downside of the transition.”

He doesn’t see that as reason alone to abandon the push for a federally-led green recovery, but “you want to be thoughtful in the design.”

Ready to inform that discussion is years of research already conducted in Canada about navigating the trade-offs of a transition away from the fossil fuels. The work includes the federal government’s task force on a just transition for coal workers, the Yellowhead Institute’s analysis of what restoring Indigenous land sovereignty actually looks like in practice, and modelling by Alberta Innovates of a bitumen industry shifting away from road transportation fuels.

The pandemic demonstrated government can quickly intervene in a time of crisis, drawing on science and policy experts to shift graph lines — and also people’s assumptions about what is possible. Apply that lesson to the climate crisis and an outdated economy, say a swelling chorus of voices. But time is running out.

“The choices that we make right now,” said Possian, “are going to shape society for decades to come.” ![]()

Read more: Energy, Politics, Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: