The patchy state of B.C.’s home-care sector is creating a huge potential for the spread of COVD-19 among vulnerable seniors.

That’s the assessment of Matthew Lowe, who has 14 years’ experience in the sector and is the founder of Community Plus Home Health Care & Nursing in Greater Victoria.

“To have all these people running around out there, with no supplies, possibly no training, providing services to our seniors in the middle of a pandemic when we don’t know where this is spreading right now, it’s insane,” Lowe said.

Lowe is not alone. A June report by B.C.’s Office of the Seniors Advocate raised concerns about the performance of the sector long before the pandemic hit.

Some 40,000 people receive home support each year. It’s delivered through the province’s health authorities by nearly 10,000 community health workers, according to that report.

The workers help people, many of them seniors or vulnerable, with daily tasks that require close personal contact — like getting out of bed, taking medicine, bathing, dressing, eating, grooming and using the toilet. Workers visit several homes a day.

Public services are delivered by a mix of health authority staff and contract agencies. Companies that provide similar services to people who pay privately are also used by the health authorities when demand rises.

Lowe said his company pays a living wage and has nurses and caregivers on staff.

But he said some companies doing overflow work for Island Health manage their workers as subcontractors and download responsibility for following requirements like having protective equipment, such as gloves, to them.

“Some of them would take gloves from other providers, some of them would actually buy their own, but a lot of them would just go out there with nothing,” Lowe said.

Some companies in the sector have a long history of cutting corners and hiring with little screening as they’ve been desperate to fill positions, he said. “A lot of them, as uncertified unregistered caregivers, may have never had a hand hygiene education in their life and that should be really scary to a lot of people, especially when you have these people basically hopping across homes across Victoria,” he said.

“What greater opportunity is there to spread an illness like this to our most vulnerable seniors besides a home-support worker? There aren’t a lot of other individuals out there who are going in, providing a highly personal service at close proximity, and doing it across a large region.”

The home-care sector is a special concern on Vancouver Island, where communities like Sidney and Qualicum Beach have among the oldest populations in Canada. But the conditions are similar throughout the province.

A media contact at Island Health declined to answer questions, saying it was better they be handled by senior officials during updates on the COVID-19 pandemic.

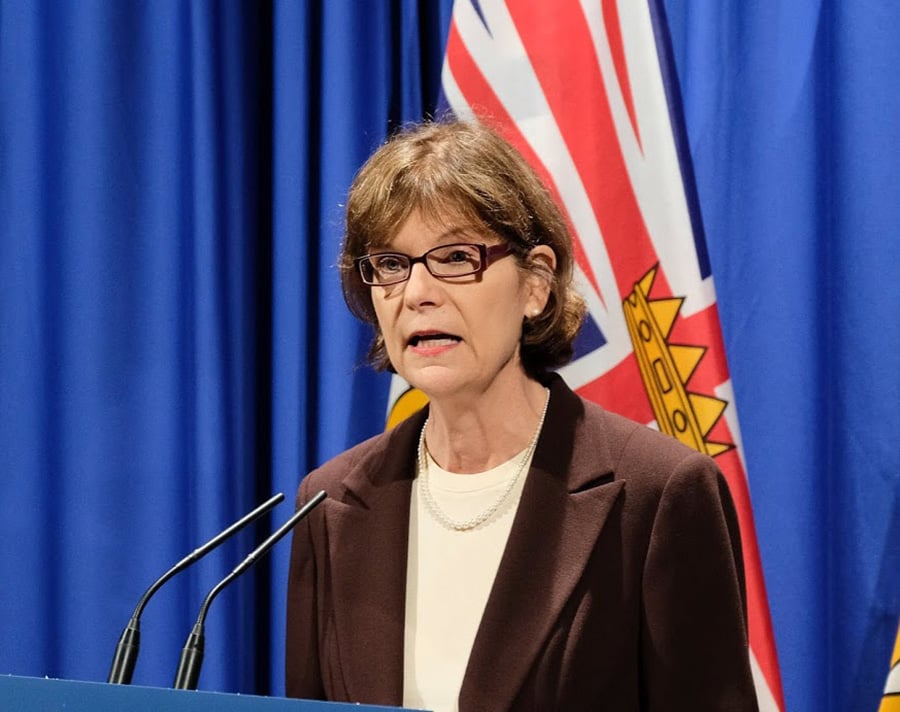

Bonnie Henry, B.C.’s provincial health officer and the lead on the response to the COVID-19 emergency, said home health care is an important part of supporting people in the community and keeping them out of hospitals.

“There are guidelines for home-care nursing in particular when they need to go in and do things in the home, nursing and others,” Henry said. “There are guidelines around personal protective equipment if needed, calling ahead ensuring people in the home aren’t sick, making sure I’m not sick myself, taking measures like hand cleaning and minimizing the people in the room when you go into the room.”

Health Minister Adrian Dix said home-care workers who support seniors and people with disabilities are fundamental to dealing with COVID-19. “Home-care workers are among the most essential people that we have and the work they do is more important now than ever, especially as we’re supporting many seniors at home,” Dix said. “It’s an issue of critical importance.”

The press conference format didn’t allow for followup questions on the measures to ensure home-support workers and companies are following protocols.

Headed into the crisis there were long-standing concerns about the sector. Last June Seniors Advocate Isobel Mackenzie released Home Support: We Can do Better.

It found that over a five-year period complaints to the Patient Care Quality Office about home support and home care had spiked by 62 per cent.

And a survey of clients and family members found 33 per cent rated the quality of their home-support service as average or below average. Fewer than half of respondents believed workers had all the skills required.

Before becoming the seniors advocate Mackenzie worked for 20 years in the home-support sector. In an interview she said she is most worried about the care that is being provided outside the health authorities and that it’s “absolutely true” that some providers cut corners.

“There are a bunch of fault lines that are revealing themselves in health care aide staffing whether it’s in long-term care homes or in the community,” she said. “This is going to be an example of one of the consequences we have of the way we’ve approached most particularly the care aides who are the ones who provide 70 per cent of the direct care in the community and in care homes. There’s no getting around it.”

The sector is coming through a time of transition. Three health authorities — Vancouver Coastal Health, Fraser Health and Island Health — last year announced they would take over delivering home-support services that for decades had been contracted out. The change brings them in line with Northern Health and Interior Health.

While the health authorities have control and oversight of the people who work directly for them, that’s not the case at the agencies that are contracted to handle overflow.

“I’m not sure, I’m not confident, they have masks and gowns and eye protection,” Mackenzie said. “My understanding is some agencies you’re an independent contractor, you actually buy your own gloves. We tell you to do all these things, but basically it’s up to you.”

She said she thought most workers would have gloves since patients would demand it, but that there was no way for officials to be sure.

Mackenzie also pointed out that home support is not licensed and regulated the way long-term care homes are, even among agencies under contract to health authorities, adding to the concern.

“If I compare and contrast, there are very robust outbreak protocols for care homes and what to do,” she said. “We don’t have that same degree of regulation or oversight or whatever we want to call it in our home-support program and I think maybe we need to look at that down the road.”

The number of contacts between various workers and multiple clients increases the chances of spreading infection, Mackenzie said. A typical client gets service twice a day and would have eight or so care workers who regularly visit. Each of those workers would be providing care in multiple homes.

And it’s unknown who else may be visiting those homes, she added. “These homes are not like care homes where you can control and know everybody who’s coming in and out.”

There’s even more risk with privately provided services.

“We don’t know when you’ve hired somebody to go in privately to help your mom,” Mackenzie said. “You don’t know what training they’ve had, you don’t know what [Personal Protective Equipment] they have, you don’t know a whole lot of things and you don’t have the ability to say ‘where else are you working’ and ‘where’d you go on your vacation.’”

And while she stressed that the important thing right now is to look forward and get through the current crisis, she acknowledged the problems with home support are the result of past decisions.

“Chickens are coming home to roost 10 years later or 15 years later around decisions that were made in a completely different labour environment of both long-term care services and home-care services to seniors.”

There’s more demand for services now and fewer people willing to accept the working conditions and rate of pay, Mackenzie said. “The labour market has shifted, and where these were good jobs at one point in time, $20- and $23-an-hour jobs are a dime a dozen now. It’s a different world.”

Mackenzie also pointed out that people want great health care, but nobody wants to pay high taxes to fund it. If home support is low-paid, unregulated work provided by people who can’t afford to take a sick day, it’s because as a society we’ve made that choice.

There are changes under way, Mackenzie said, including restricting workers from providing service both in care homes and in home care.

“They’re working on it,” she said. “There are a lot of moving parts and a lot of players. That’s the other thing that’s becoming apparent, is it’s difficult when you have a lot of players. But they certainly know what has to be done and they are certainly working to make sure it gets done.”

Another option is to assess which home-care services are essential, Mackenzie said. There are people who need help with basic tasks like eating or taking medicines, but something like laundry can be done less often. The sector already makes that kind of adjustment during snow storms or labour shortages, she said, but with the COVID-19 pandemic may have to run that way for even longer.

Lowe said there need to be society-wide changes that allow people to make good decisions. Making sure everyone can take paid sick days is a necessary step, he said, but so is providing a basic income so that everyone can pay their bills. Low-paid workers in the sector might feel pressure to keep working even if they’re sick.

“To give people basic security allows them to actually look beyond themselves and make better choices going forward,” he said. “Right now you have so many people out there who are constrained by poverty and they can’t make good choices because they have no security to know they’re going to have something stable in the future.”

Lowe’s company is committed to paying a living wage, but he knows of many home-support workers who live paycheque to paycheque and have little security.

“They get treated like gig economy workers even though no one is considering them that way. It’s completely insecure employment, it’s not humane. We shouldn’t allow it.”

Mackenzie said for now the focus has to be on getting the message to all health-care workers, wherever they work, to follow safety directives, including around protective equipment, and to stay home if they’re not feeling well. The numbers of cases in B.C. are still relatively low, she added, so there is still some time to prepare and make changes.

“As we look back on all of this, and at some point we will, and we look at what were the biggest challenges and why, I think some of these questions that some of us have been asking are going to be raised again,” she said. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice, Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: