Before I tell you about Lois Milsom and her quest to build townhouses on Vancouver’s prestigious Point Grey Road for a school project, I have to tell you about an important birthday we should commemorate.

British Columbia’s first condominium project turned 50 this year, signalling the beginning of our urban transformation of development, densification, displacement, speculation and globalization.

A story in the Vancouver Sun mentioned this auspicious year, but it didn’t acknowledge the quinquagenarian project in question.

Who is the proud developer? Where is it located? Was there a party?

After all, in Edmonton’s suburb of York, across from a Catholic elementary school, there is a cairn and a plaque at the Brentwood Village townhouses celebrating that project as the first condo built in Alberta and Canada in 1967.

Yes, Edmonton — not Vancouver, despite being home to iconic, glassy waterfront condo towers and Bob Rennie, the property marketer colloquially crowned the “condo king” — has claim to this slice of Canadian housing history.

Considering the great condo-ization of B.C. cities this half-century, surely our province’s first project would have a commemorative marker of some sort.

I turned to Douglas Harris, a professor who specializes in property law at the University of British Columbia. If anyone knew about B.C.’s first condo, it would be him.

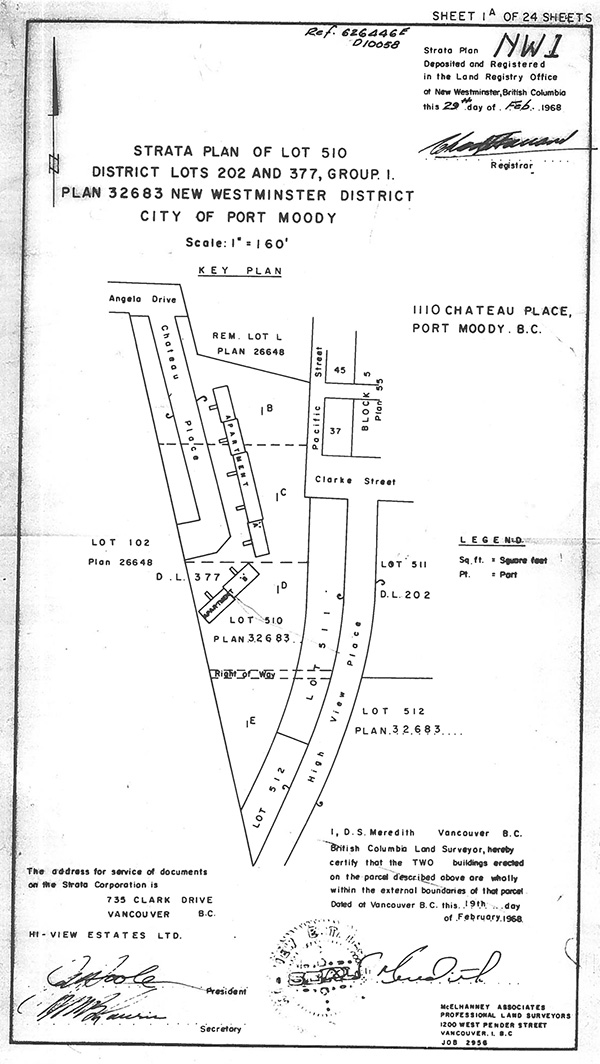

Indeed, Harris showed me the registration for condo number one: Chateau Place in Port Moody. Like Alberta’s first, this was also a townhouse project. Dawson Developments, formed by the late Jack Poole and the late Graham Dawson, both well-known local builders, developed it in 1968, two years after B.C. legislated condos as a new kind of property ownership, changing the development game forever.

I was further intrigued when I found a 2012 article in Vancouver Magazine that cited another big local name who worked on the project: the firm of the late architect Arthur Erickson, the West Coast’s Frank Lloyd Wright.

But when I showed the Port Moody townhouses to Erickson’s nephew Geoffrey, who manages his uncle’s website, he said it “doesn’t look like an Erickson project.”

I couldn’t follow up with any of these giants who left their mark on Vancouver. Arthur Erickson, Jack Poole and Graham Dawson all died in 2009 in May, October and December, respectively.

But then I received an email from another Erickson: Christopher, also a nephew of Arthur, who is Geoffrey’s brother. He suggested that there was a Vancouver condo project before the Port Moody townhouses, and before even the Edmonton townhouses.

Could it be true that Vancouver was home to Canada’s first condos after all? If yes, then Vancouver deserves a plaque at least as nice as Edmonton’s.

But how could it be true if condos were not created as a form of ownership in B.C. until 1966? The project Christopher spoke of was completed in 1965.

“Lois Milsom might be able to answer some questions about Point Grey Townhouses, if you are interested,” Geoffrey Erickson told me.

And that was how I found myself in Milsom’s living room, to see if she might’ve been the first condo developer in Canada.

Mrs. Milsom and the missing middle

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, completed in 1935, is a Pennsylvania house built partly over a waterfall of Bear Run, a tributary in the Appalachian Mountains. Fallingwater has been named one of the best works of American architecture, and it changed Lois Milsom’s life.

“If somebody could build like that, then I want to learn how to build,” she said.

Milsom enrolled at UBC to study architecture in 1956. She was older than the other students, already married with three children. During her time at the school, Paul Merrick was a student and Arthur Erickson was a professor. This was before Erickson would work on projects like Simon Fraser University and the Museum of Anthropology.

In those days, Vancouver’s look wasn’t much different from Vancouver in the 1930s. There was no downtown skyline yet.

On a trip to Denmark, Milson was inspired by a type of building that was rare back home: townhouses. Detached houses dominated residential Vancouver, though there were some tenement-style rental rowhouses in Strathcona and on the south shore of False Creek built early in the century.

Even today, townhouses, a type of “missing middle” housing between low-density houses and high-density towers, are sorely underrepresented.

For her graduation project, Milsom decided she would do something about that. She would build townhouses herself.

“Well, it’s a good idea,” she remembered a mentor telling her, “but it would have to have a location.”

So Milsom kept an eye out. One day she happened upon the perfect property on a prestigious Vancouver street people called the Miracle Mile in the 1960s, and later the Golden Mile and the Road for the Rich.

“I found an old three-storey yellow brick house vacant on a great big piece of land on Point Grey Road,” she said. “Gee, I wonder who owns that! I was driving by that for years and I didn’t pay attention to it.”

That house sat on a 198-foot property, six times the typical 33-foot Vancouver lot.

“It had been vacant for five years,” said Milsom. “Can you imagine? One hundred and ninety-eight feet of waterfront!”

Though it’s been over five decades since then, Milsom still talks about that property in disbelief. “I had to buy it,” she said with a laugh.

Finding a site was the first challenge. Next was convincing the bank to give her a loan. In those days, Milsom says it was “impossible” for a woman to do so in her own name.

“I had a philosophy: never let anybody say no,” she said. “Just the minute someone’s about to say, ‘No, no, no possible way,’ I’d drop something and change the subject and then start over again.”

With that spirit — and her husband by her side for the bank visit — Milsom received the loan. “The very good bank allowed me when no female had ever handled a loan that size on their own signature before. It was a bit groundbreaking.”

Milsom says the bank told her it was the first time a woman in Canada had taken out a six-figure loan without a co-signer.

She purchased the property with the yellow house for $80,000 in 1963, equivalent to about $660,000 today. It turned out it had already been subdivided into six lots, so Milsom kept one, sold the other five, and promised the clients that she would act as the developer and deliver the townhouses to them upon completion. To me, Milsom’s arrangement sounded much like today’s condo presales.

Milsom naturally chose the Erickson/Massey firm to design the project (“I couldn’t think of anyone else I would even consider,” she said), and Hans Haebler, another well-known Vancouver name, to build it.

The next challenge: convincing city hall to let her develop the townhouses.

Staff were not pleased. This wasn’t a multi-family rental development with a single owner. Milsom wanted the townhouses to be separately owned. Again, this was 1963, and there was yet no such thing in Canada as condos.

Staff suggested that Milsom build separate houses with side yards, but she didn’t want to squander the square footage for “little places for garbage cans on the waterfront.” Staff didn’t like the idea of separate owners sharing a driveway, let alone a building.

And so, the process dragged on for over 2.5 years.

In 1965, Milsom decided to speak to each city councillor individually about the project. To one councillor serving his first term, she issued a challenge: “If young councillors like you won’t stand up for a new idea, what hope does the city ever have?”

That councillor was Bob Williams, who would later become an NDP MLA.

“The other city councillors didn’t have a clue, to tell you the truth,” remembered Williams. He had the benefit of being an urban planner, a graduate of UBC. “I thought it was a really smart idea. Why would you waste a waterfront lot? So why don’t we give it a go?”

After talking to the councillors, Milsom presented the project to them officially at city hall on a Wednesday.

“When I walked in, everyone burst out laughing because I had gone to each of them,” she said. “That was when I knew I had it.”

I looked in the Vancouver Sun to see how many times total Milsom pitched the project to council because she couldn’t remember. The paper said it took her five tries.

Townhouses on Point Grey Road

There were rumours among the neighbours that a motel, or perhaps a health centre, was coming to Point Grey Road. But after nine months of construction, a lonely yellow house on the waterfront became many homes.

Milsom moved into one of them, along with the buyers who became her neighbours: an engineer; a woman named Betty Marshall who ran the contemporary New Design Gallery; a woman from Kamloops with two sons who Milsom remembers saying that she “promised the children she’d get a waterfront property;” and Ralph Shaw, the president and later vice-chairman of forestry giant MacMillan Bloedel.

Of the six lots, Shaw bought two of them, making his home the largest of what then became five townhouses at 5,608 square feet.

The other clients had different tastes too, and the homes varied in price and size. One was around 2,500 square feet, another at 2,900 square feet. One had an indoor pool; one had an outdoor pool. Furniture between the clients was also nothing alike; there were pieces in Mexican, Chinese, 17th-century French and contemporary styles. (Milsom notes that one of the clients had an architect friend participate in the design of their home. “It was the poorest design of the lot,” she said.)

The entire project would require 120,000 bricks, exhausting what supply Vancouver had at the time, causing Haebler the builder to truck in 45,000 more from Seattle.

“It’s a pretty exotic location,” said architect Nick Milkovich, who began working for Erickson/Massey three years after the townhouses were completed. “You know Vancouver — the mountains are in the north and the sun is in the south, and those units all captured both. Very thoughtful.”

The year 1966 rolled around, and condos were officially legislated in B.C.’s Strata Property Act. With the completion of the townhouses in 1965, Milsom was ahead of the province by one year and ahead of Canada’s first official condo development in Edmonton by two years.

“[The Point Grey Road project] was a condo project as you’d think today,” said Milkovich. “You build it and sell it.”

Sherry McKay, an associate professor at UBC’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, calls them “brilliant.”

“It’s interesting that you had this kind of density in the ’60s when there was so much discussion about the single-family home,” she said.

In 1966, Vancouver Life magazine hailed the experimental project: “... the importance of the townhouses lies in the possibilities that are opened for future building in Vancouver.” It wasn’t talking about affordability, but new types of creative housing designs it could help encourage. “When this new civilized way of living spreads out from 3271 Point Grey Rd., much of the credit can go to Lois... who was stubborn enough to fight city hall.”

Five decades later, Vancouver’s strategy to increase gentle density in detached-house neighbourhoods is in limbo, halted by debate over a type of residence even less disruptive than townhouses: the duplex.

My guess is that Erickson would’ve been frustrated by this slow progress. He was of the mind that regulatory committees strangled creativity. When the townhouses were completed, Erickson told the press it was the most difficult project he had worked on to date, and by then that included Simon Fraser University. City staff gave him headaches throughout the design process, and in the end, he had to submit to the loathsome requirement of including a garage opening to the street for each home.

Even in the 1960s, Erickson recognized that Vancouver needed more “missing middle” housing types. According to the Stouck biography, he believed that townhouses were better for cities than vertical apartment buildings, which he called “notoriously inadequate,” because townhouses had a better relationship with the city.

Didn’t get an A

By now, you might be wondering: did Milsom get an A for the townhouse project?

In the end, the school denied it as a thesis project. Milsom did not graduate.

“We found her documents,” said McKay of UBC’s architecture school. “She did all her courses, but there’s no actual record of the project — and there wouldn’t be unless she graduated.”

At least Milsom was left with a townhouse to enjoy.

Her family only lived in the townhouse for five years, but Milsom has fond memories there, from parties to simply enjoying the view from the rooftop deck.

“My kids loved it too,” she said. “Once I was over at Shaw’s for a drink before dinner. (It takes a long time to do that.) When I came back to the house, my middle daughter, who’s very social, had about 30 of her friends there! And they were climbing on the railing over the courtyard and they were so shocked when I came back that they practically fell off.”

Over the years, Milsom developed real estate in both B.C. and California. (She saved a newspaper clipping with a headline that singled her out for being a “woman developer.”)

In Vancouver, she was also involved in the arts and politics, as one of the founding members of the legendary reform party TEAM (The Electors’ Action Movement) which helped stop a freeway project that would’ve trampled the inner-city East End on its way downtown.

Milsom and Erickson remained close friends, and Milsom was present when Erickson died — with Erickson’s niece Emily and her husband David — on May 20, 2009.

If you want to look at the townhouses, they’re still there on Point Grey Road today, between house numbers 3267 and 3293. The largest of them is worth $21 million, according to BC Assessment.

Though we cannot call Lois Milsom Canada’s first condo developer, she pulled off a project still considered cutting edge in city struggling to tweak its single-family neighbourhoods.

“It made it easy for me to do anything after that,” Milsom reflected. ![]()

Read more: Municipal Politics, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: