Across North America today, precious urban housing space is languishing right under our noses — or more precisely, under our wheels.

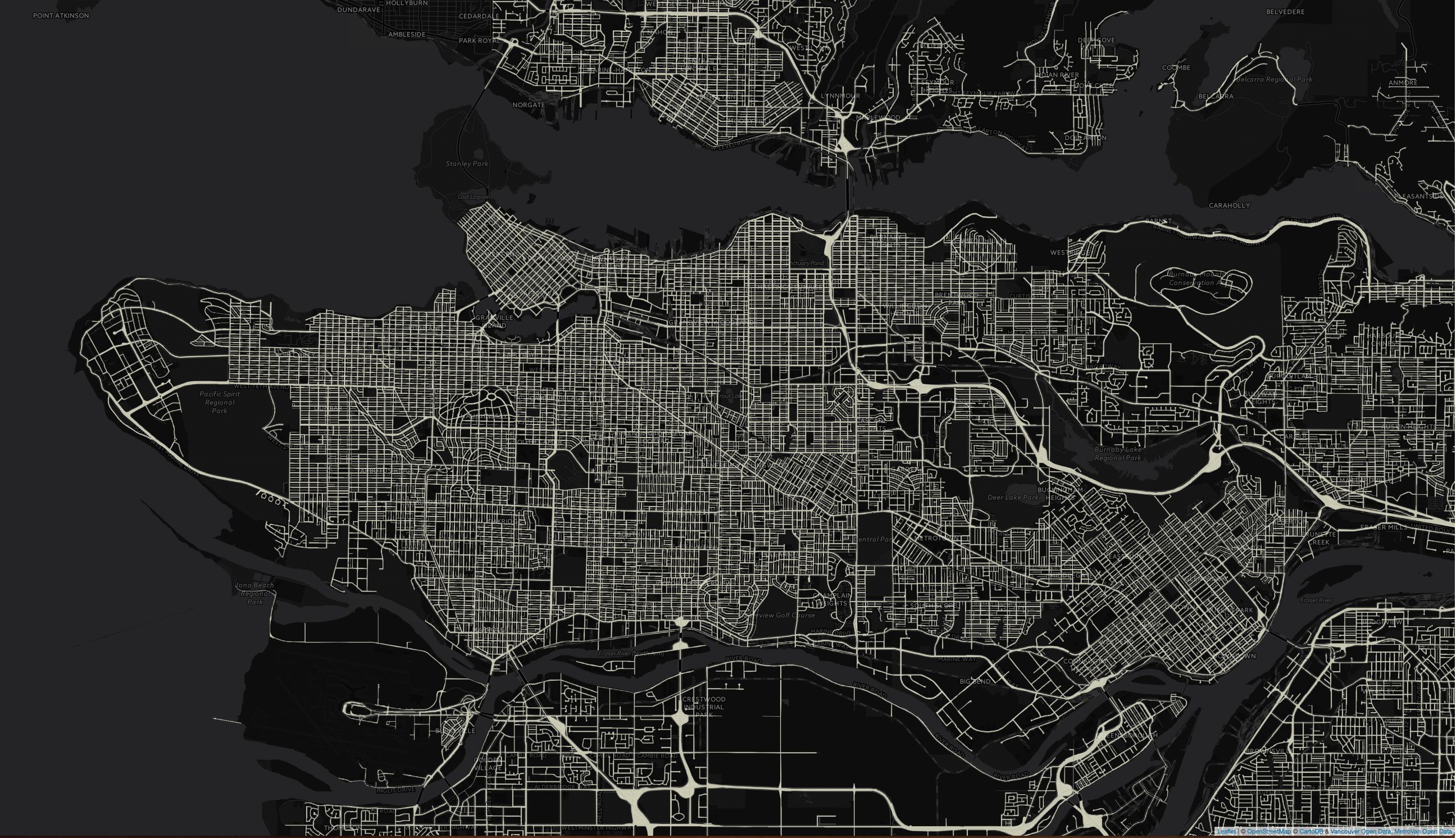

In the City of Vancouver alone, it’s estimated that over 30 per cent of all land — worth an estimated $48 billion — is tied up by our roads, parking lots and alleys. This vast urban “greyfield” constitutes the largest tract of un-built space in many cities, raising exciting questions about how it could be used to make urban density liveable, family friendly, and maybe even more affordable.

Suburbanites and rural dwellers will continue to rely on private vehicles. But in a future world where urban people work from home more, rely on car (and bike) sharing, Uber-like services and beefed up public transit, inner cities will be able to repurpose a lot of precious space.

“The old way of doing things if a place gets too congested is to just build more roads,” says architect James Cheng, of Vancouver’s James KM Cheng Architects. “Or make them wider. But I think the new concept is not to expand the cars, but taking the roads back. What else can we do with them?”

Reclaiming the urban ‘greyfield’

We seldom think about it, but our roads and alleyways occupy enormous tracts of valuable land. Consider: the City of Vancouver has more than 1,400 linear kilometres of roadway, including over 1,000 kilometres of local roads and 650 kilometres of driveable lanes and alleys; a typical street in Vancouver is 66 feet wide, while larger arterials are 80 feet.

Then there’s parking. Across much of North America, new buildings must by law be accompanied by parking spaces. In many suburban municipalities there is currently a requirement for at least two parking spaces for each townhouse, plus visitor parking. The same goes for virtually every other kind of building in our cities. This comes at an astronomical cost to the builder, which is typically passed on, whether the occupants drive or not: each underground parking space adds anywhere from $35,000 to $50,000 to a development’s cost, depending on location and the depth required.

But with fewer private cars on the road (imagine your self-driving shared Tesla picking you up and dropping you off at the mall, then humming off to pick up another passenger), architect and planner Michael Geller says, “the parking requirements of yesteryear will no longer be applicable. We’re starting to see that happen already.

“It’s not a stretch to imagine that a lot of parking lots, especially around shopping centres, churches and institutional buildings, will ultimately be redeveloped with housing and other uses.”

Vancouver, meet Barcelona

In the coming decades we can expect to see under-utilized driving lanes disappear, says Geller, as bicycle lanes are added, sidewalks widened, and more street level activities like cafes and outdoor shop displays appear. In short, inner cities could start to look more like places never designed for cars in the first place. “You just have to look at older European cities to see what our future might be,” he says.

Take Barcelona. L’Eixample was a model, master-planned neighbourhood planned more than a century ago, and is composed of uniform, octagon-shaped six-to-eight storey apartment buildings, where the residential units hug the exterior of land parcels, with courtyards in the middle. At intersections the building corners are cut off to create little retail plazas. The area has had its critics, but compared to many North American cities, this is truly walkable, family-friendly density: it was designed so that 50 per cent of all street space is dedicated to pedestrians, with the rest shared between all other traffic.

“I can envision some neighbourhoods close to transit and city centres being developed with that type of six-to-eight storey buildings,” says Geller, “with some tower buildings mixed in, as an alternative form of densification to the high rises that we’re so accustomed to today.”

Lower-rise alternatives to ‘city of glass’ towers?

Liberating urban space from cars could also make room for building forms more family-friendly than the inverted T of the socially-isolating high-rise tower atop a wider, low-rise podium that’s particularly ubiquitous in Vancouver’s downtown “City of Glass.”

Architect Oliver Lang, of Vancouver’s Lang Wilson Practice in Architecture Culture, points to Singapore for other forms, including a famous development called “The Interlace.”

Built across eight hectares, the development consists of 31 apartment blocks — each identical in length and six storeys high. The blocks are stacked to form a hexagonal pattern, forming eight open, permeable courtyards. Living and communal spaces are interconnected with the natural environment; it is people-dense and close to green space at the same time.

Lang sees Interlace as a sort of missing link between what he calls the North American “dichotomy” of autonomous living, whether it’s in towers or the disconnected suburban single family house.

Gil Kelley, who worked in San Francisco and Portland before becoming Vancouver’s new director of planning, sustainability and urban design, has also visited The Interlace and agrees there are lessons to be learned there.

“I think there are some principles that could be used in Vancouver, [like] the notion of creating projects that have green space and common space on multiple levels and in various ways, sort of rethinking our standard building types here, like the podium and tower,” he says. “Perhaps the most intriguing [thing] are the semi-public, communal gathering spaces.”

Courtyard housing for the missing middle?

Kelley acknowledges that cities like Vancouver currently do a better job of building for low and high incomes than for the middle segment occupied by working families. To help address this “missing middle,” he points to the courtyard housing concept, an old building prototype that dates back to the Romans, and re-appears in places like Barcelona’s l’Eixample, and in more recent times, in 1920 to 1940s-era streetcar neighbourhoods in places like Portland.

A courtyard apartment, generally speaking, consists of multiple housing units collectively oriented towards shared outdoor space, usually with some sense of enclosure. Units have either their own entry, or as many as three units sharing a single common entry. It’s typically medium-rise, high density urban living, but offers the prospect of ample (safer) space for kids, community connection, and room for a family garden patch.

And as space opens up from under-utilized urban parking lots and roads in the future, it’s possible that the courtyard apartment will be making a comeback.

Back in 2007, Portland held an international design competition for courtyard housing, with a goal of promoting courtyard apartments as urban infill — in particular, affordable, higher-density housing for families with children. (The winning design was later adapted and built by a community land trust.)

The appeal of this building form, says Bill Cunningham, a planner at Portland’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, is that it is high-density habitat for families that can provide many of the amenities of single family homes without the astronomical cost. “Private yards [in the city] tend to be almost postage stamp sized, but a courtyard oriented design provides that opportunity to have a larger outdoor space, and that meets some of the aspirations people have for single family houses, like useable outdoor space for kids and gardening.”

For a city like Vancouver, Gil Kelley says, the “transition zones” between transit-area towers and single family homes could offer opportunities to build more courtyard-styled apartments and housing. “What does the medium density look like and what kind of courtyard forms can we build? That’s a whole new territory for architects and urban designers to push into.”

Densifying airspace: ‘It’s almost like the Jetsons’

And when it does come to concentrating future density at transit centres (transit “nodes” in planner speak), there’s more North Americans can be doing beyond building monolithic, spike-in-the-sky towers. All we need to do is look to Asia, says architect James Cheng, who is intimately familiar with the human-dense, public transit-centric, cities like Singapore and Hong Kong.

Cheng points to developments like Beijing’s Linked Hybrid, which at 220,000 sq. m is bigger than New York City’s Grand Central Station. It’s a largely public space where commercial, residential, educational and recreational uses meet and converge on three separate levels — below ground, at grade, and in the sky.

Such tower developments employ “sky bridges” that connect separate high-rise buildings mid-air. “It’s almost like the Jetsons,” Cheng says: with the potential to develop an above-ground city network where you can move around the city without touching the ground or a car.

Super transit nodes in three dimensions

As radical as this air-level community sounds, many cities are already exploring this idea — underground pedestrian networks where you can move around to separate buildings for multiple city blocks without coming up to the street (think Vancouver’s Pacific Centre or Toronto’s 30-kilometre underground PATH walkway system). The innovation, says Cheng, is to move these networks into the air, where instead of darkness, there is light.

Calgary’s Plus 15 does this to a degree already, and many cities already employ sky bridges between towers.

For Canadian cities already committed to building density around public transit stations, adding future density could mean taking better advantage of the air space. This can be achieved by building up around densified transportation supernodes anchored by sky-bridge-connected residential towers, creating new (above ground) room for schools, retail, institutional buildings, and even green spaces/parks.

On the ground, in the meantime, much of the land historically consumed by cars and parking can be greened, to create the kinds of urban spaces people want to frequent. In this three-dimensional North American urban core of the future, the car is not only inconvenient, it’s irrelevant. The best part of this, Cheng says, is that it’s not science fiction — it’s already here.

“The trend really is to look at the communities that have a lot of transit, like Hong Kong, Tokyo, Singapore, and even [cities in] Russia,” he says. “Their subway stations are like three dimensional cities.”

As for the family car, in the city of the future, who’ll need it? ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Housing, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: