If you live in Greater Vancouver and do not yet own property, any dreams of buying a single-family home with a yard probably died long ago.

But even with the old-fashioned single family home out of reach of most, there are still opportunities to find room in our cities for more than lottery winners. Ramping up so-called “gentle density” — infilling unoccupied spaces in a way that doesn’t change an existing neighbourhood’s character — isn’t a complete answer to the current crisis of affordable housing supply, but it’s a good place to start.

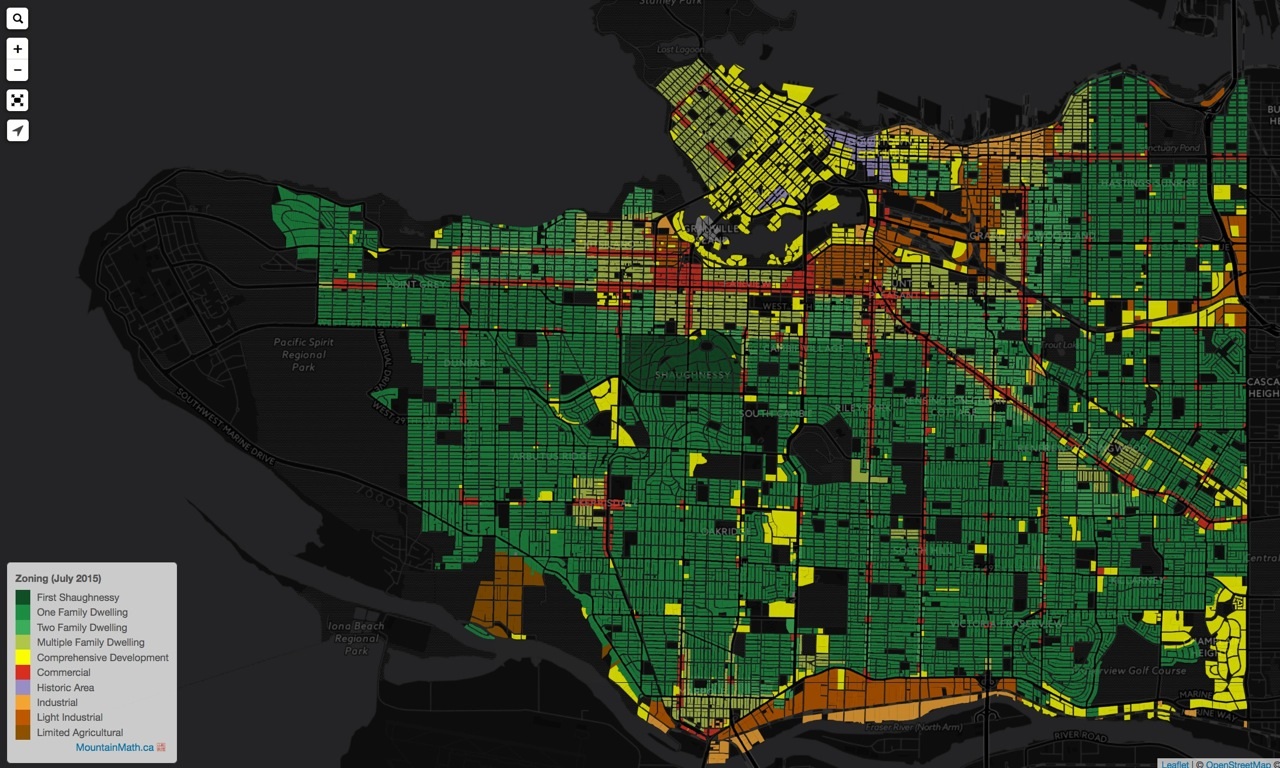

In the city of Vancouver alone, more than half of all zoned land caters to this unattainable dream, zoned ‘RS’ (single family). Yet on a standard single family lot (about 33 x 120 feet in East Vancouver, typically bigger on the West side), you can build more than a single house. In addition to a basement rental suite, if the yard is big enough and backs onto a laneway, you might also build a small separate living unit there.

But that, people in the business say, is just the start of what Vancouver could do with its “single-family” lots. And it can be made even easier and cheaper.

Build cheaper modular laneway units

Geoff Baker, co-founder of Westcoast Outbuildings, builds laneway houses in his North Vancouver plant. The company just launched a new line of “modular laneway houses” that range from 288 to 528 square feet in size, and start at just under $100,000 plus another $40,000 or so in site servicing costs, varying on municipality.

The modular construction, he says, is a key to making laneway housing less expensive. In the business-as-usual approach taken for most laneway houses, 99 per cent of which are built on site, customers incur the cost of any delays in the project, including taxes and other holding costs, mortgages, and lost rental income.

By contrast, modular buildings are assembled under controlled conditions at a facility and often delivered complete to their final site. In Westcoast’s case, the company also stickhandles permitting and other site-specific arrangements that may take time.

“At the same time as all of the site preparation is being done such as the water and sewer lines, hydro, and foundations,” says Baker, “we are building the laneway house in the factory. This parallel construction process [can] cut literally months off a building project.”

But permitting regulations hold laneway housing back, says Baker. Vancouver, for example, requires one to have independent connections to water, sewer and gas from the existing house on the lot — explaining some of those $40,000 in site costs.

Cheaper would be to allow “piggybacking” of services: rather than connecting the laneway house directly to the main service lines in the street, a builder could be allowed to tie in to the services used by the existing house on the lot. Baker says this approach is currently allowed in North Vancouver.

And if Vancouver in particular is serious about more laneway homes, he adds, it should speed up permitting — a process that can take up to eight months even for a small laneway house.

Infills protect heritage for more residents

An old mansion off Vancouver’s Commercial Drive was built for prominent doctor and politician Thomas Jeffs in 1907. After Jeffs’s death, the turreted house was carved up over time into units that provided rental housing for over 80 years.

In 2012, James Evans redeveloped the house with architect Timothy Ankenman, gutting it, moving it to the edge of the lot, and redistributing the interior into seven new units. Moving the historic mansion made room for 13 two-and-a-half storey townhomes on several adjoining lots that had been part of Jeff’s original parcel.

And in exchange for saving the structure, the city relaxed street setbacks and allowed about 30 per cent more unit density than it otherwise would have. (So-called “Heritage Revitalization Agreements” can get even larger density bonuses).

Evans says that getting the city to permit a heritage infill like this one takes about twice as long as for a new a duplex, up to 18 months. Faced with such daunting timelines and complexity of approvals, most owners (and small developers) will rip down an old house if they can, and build something new.

The Jeffs development was a sore spot to some because it necessitated the loss of precious rental housing in a community where “renovictions” have become commonplace. Evans says about 17 people lost their rental homes, but counters that over 50 people are now living on the same footprint, including several families (nine babies have been born there since it opened in spring 2013).

“I wanted to create ‘affordable’ family housing,” Evans says, “and I use quotation marks because there’s no such thing as affordable in this town.” Nonetheless, he says, “I was able to bring out three-bedroom townhomes for $100,000 to $150,000 less than a comparable three-bedroom duplex.”

Replace single-family houses with more duplexes

Right now, single family zoning in Vancouver means just that: it doesn’t allow two principal dwellings on a single lot. (Toronto’s Residential Detached zone category similarly requires a maximum of only one “dwelling unit” per lot, and applies to most of the suburban areas of the city.)

Architect and planner Michael Geller says a simple step to gently fit more people into available space is to allow more single-family homes to be replaced by duplexes.

New Westminster is doing that now: rewriting its Official Community Plan to allow duplexes to be built on lots over a certain size in single-family neighbourhoods. The change could be in place as soon as spring 2017.

While duplexes in places like Greater Vancouver may still not be affordable to the average wage-earner, they provide downsizing options for some, and a cheaper alternative to a single family home.

Geller says cities can go a step further, and make it easier to allow a duplex with a laneway or coach house, and in the lower level of the duplex, have one or two garden or basement suites. “All of a sudden you’ve now created the potential for four to five units on a 120 x 50 foot family lot, which from the street, may not look significantly different from the single family houses next door.”

To let this happen, cities need to change their zoning to allow creative use of what’s called the “floor:space ratio” — the ratio of the building area to the lot size. Instead of one 3,500-square-foot house, rules might instead allow two 1,750 sq.ft. flats, or four dwellings of 900 sq. ft.

Trying out density in neighbourhoods

Some of Vancouver’s suburbs and neighbours — places like Richmond, Surrey, and Seattle — are already fitting as many as four homes on single family lots: generally two townhouses along the street and two along a lane, all with their own street-level surface garages.

A variation is the “stacked townhouse”: two townhouses at grade and two above, each with their own entry from the street. Either configuration can be designed to fit in nicely with a single-family house on either side.

Vancouver is exploring the same idea. In its Norquay neighbourhood, along a diverse stretch of East Vancouver’s Kingsway, the city hopes to achieve more “affordable entry-level home ownership opportunities, particularly for families, while retaining the ability to include rental housing” by allowing stacked townhouses and encouraging multiple small dwellings or duplexes on bigger lots and assembled sites in certain parts of the neighbourhood.

Since zoning changes were approved by council in 2013 and 2016, the city has received 138 development permit applications under the new rules, including 65 two-family dwelling and 14 “multiple dwelling” developments.

A spokesperson for the City said that recent community plans illustrate how the idea is catching on. The latest phase of the plan for the city’s Cambie transit corridor targets areas off that main street for townhouses, row houses, duplexes and triplexes.

The plan could allow for as many as 4,000 townhouses on more than one-fifth of single-family lots in the corridor. Prezoning for townhouses and apartments on over 50 acres in the Marpole neighbourhood near Vancouver Airport has attracted development proposals for 500 new housing units — 300 of them in townhouses.

Geller, a city planner as well as an architect, cautions that Vancouver shouldn’t bulk up every single-family zone for multiple dwellings. Instead it should prioritize zones close to main streets, transit, parks, and community amenities.

Even all of these changes won’t answer the city’s, or Canada’s, diverse housing challenges. But in places where rising populations and need for housing mean fitting more people into the same space, “gentle” density is a start. In a future report, I’ll look at where we could go from there. ![]()

Read more: Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: