Nestled near the heart of downtown Vancouver is a neighbourhood unlike any other in the city.

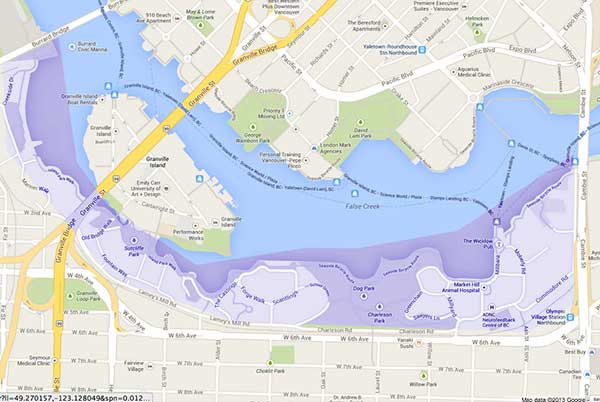

Even a cursory stroll through False Creek South -- a jumbled expanse of townhouses and low-rises bounded by the Cambie and Granville bridges -- reveals surprises: An urban waterfall. Stones oddly embedded in every roadside wall. Donut-shaped enclaves and hidden corridors. A labyrinth of swirling, cobbled streets forever closed to cars. Communal courtyards that lead into other courtyards.

The community might seem eccentrically laid out, but few Vancouverites know what it is that makes False Creek South truly unique. In fact, it's a worldwide case study in urban planning, on land almost entirely leased from the city itself.

"It's kind of a little oasis," says Kathleen McKinnon, president of the False Creek South Neighbourhood Association (FCSNA), "but not just for the people in False Creek. It's an oasis for a lot of people throughout the city.

"There's so much green space -- a waterfall, the seawall, the little boats -- that are enjoyed not only by us, but by a lot of others. We ride our bikes everywhere. When we go for walks, we always meet several people we know."

'An experiment to use fewer cars'

Locals and passers-through alike praise the neighbourhood. Many spend a passing moment in the typically quirkily named Leg-in-Boot Square. Others gather over pints in the Wicklow pub at Stamps Landing or chat as their kids play outside the elementary school that serves co-op members, low-income renters and condo owners alike.

"We were basically an experiment to use fewer cars," says Rider Cooey, one of the False Creek Co-operative's first batch of residents in 1977.

In fact, False Creek South was much more than that: a Trudeau-era experiment in urban social engineering where physical space and consciously contrived demographics were intended to create a new community from scratch, in close harmony with its unique setting.

But while False Creek South has been unique from the outset, today it also epitomizes some of Vancouver's most urgent current crises around affordable housing, rising inequality and bewildering urban change.

The project was built on former industrial land reclaimed by the city. To accommodate a five-year building schedule, the city signed land leases for each phase separately. Now, those 50-year leases are entering their home stretch: the first is set to expire in 2022. That's left the intentionally diverse community looking apprehensively to the next decade.

Indeed, for the one-third of the community who own their units, the looming expire is already causing problems. They have found banks reluctant to finance or renew mortgages on their properties. Other residents worry about whether the city will renew the leases that underlie co-op and rental tenancies as well. And everyone wonders what compromises may have to be made in the unique community arrangement in order to secure its future.

Their fear: will Vancouver's 40-year experiment with a carefully planned, mixed-income, livable neighbourhood be able to maintain its character and diversity in the face of development pressures? And will its long-time residents be able to afford to stay?

'Revolutionary'

Dreamed up in a distant time when creative governments were willing to experiment, False Creek South boasts a very conscious blend of income levels, the largest cluster of co-operative housing in the province and the city's only direct-representation neighbourhood association.

"We represent buildings throughout the Creek, from Cambie all the way to the Granville bridge," explains McKinnon, leaning on her balcony overlooking a vast green lawn shared by low-rise buildings on three sides; on the fourth side is the popular Seawall and waters of False Creek itself. "We're unique in that all the other neighbourhood associations within the city are groups of interested people, sometimes with an axe to grind on one issue or just one area."

What made False Creek South possible was an unusually auspicious conjunction of political stars in the mid-1970s.

Voters in British Columbia ended decades of Social Credit rule in 1972, to sweep the New Democrats under activist leader Dave Barrett to power in Victoria.

The next year a worldwide energy crisis hit, and reducing fossil fuel dependency became an urgent priority. The year 1973 also saw Vancouver send The Electors' Action Movement (TEAM) to city hall; part of mayor Art Phillips' vision for a livable city was to unlock a huge tract of city-owned land downtown on which to try something entirely new.

By 1974, then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau had been three-times elected, and was throwing federal cash at the co-operative housing model and other social experiments across the country (like Dauphin, Manitoba's experiment with a guaranteed minimum income).

In 1975, the Greater Vancouver Regional District unveiled its "Livable Regions Strategy" to boost high-density building, preserve urban green space, and promote public transit.

The model that emerged was a community that deliberately incorporated one-third of its residents in co-operatives, one-third in both subsidized and market rental housing and one-third as condominium owners -- all living together on reclaimed industrial lands.

"It was a different time -- Trudeau's era," said Beryl Wilson, one of the earliest owners of a townhouse on the Seawall and for decades editor of the community's now-defunct weekly newspaper. "It was so revolutionary.

"A lot of people thought it was a ghastly mistake. Some people drove over the Granville Street bridge and said, 'That will be a slum in no time!' Other people thought we were mad. There wasn't anything like this kind of development, and there hasn't been since."

It hasn't all been easy over the years. Businesses originally inserted into the community -- "seeded," as one initial architect phrased it -- didn't all take root. Many struggled for years before eventually moving out. The limited lifespan of many of the buildings gradually became evident, as construction standards were revealed to be woefully inadequate to the humid West Coast climate, and leaks took their toll.

Nonetheless, False Creek South became an urban planning Mecca, attracting city designers from Europe and the U.S. eager to learn from its diversity-rich model -- and from its mistakes.

A new lease on life?

Now, as the community nears 40, its almost 6,000 residents gaze across the Creek to a vastly changed city of glass condominium towers and skyrocketing property values. The land beneath their buildings still belongs to the City of Vancouver. And the simmering question is whether the city will let them keep it, once their leases start to expire, in as little as nine years.

The community has overcome its share of other hurdles already. For years it had to pay for its own transit service. Owners and co-op members alike were hard hit by water leaks that beset many buildings of their era. At times parts of the community lived under tarps, and many owners were forced to re-mortgage their homes to pay their share of the millions of dollars in repair costs. What little federal funding the project still receives will dry up by 2019.

Tomorrow: False Creek South's first tenants assess their 'revolutionary' experiment. Find the series so far here. ![]()

Read more: Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: