[Editor's note: The Tyee Solutions Society's Pieta Woolley has been writing about the reasons why many graduates of the provincial foster care and child protection system become homeless as young adults. As 620,000 B.C. children and teens return to school, she looks at why the "launch" from adolescence to financially-independent adulthood is proving so hard for so many -- not just the most vulnerable -- and some ideas about how to help. Today, Woolley explores what's missing from today's B.C. economy that once helped untrained young people get their start. Find the series so far here.]

"So foster kids are flunking out of school. I guess the world always needs plumbers, eh?"

The person who said this to a reporter heads a national youth organization. Her offhand comment shows how thoroughly the mythology of well-paying, easy-entry jobs persists.

Once, a generous handful of sectors offered employment and family-supporting incomes to the least skilled and those who ditched school early. These days, that's one in five B.C. teens and most of those who graduate from the provincial foster care system.

But times have changed. Over the past 30 years, a perfect storm of social forces, from environmental collapse to labour-replacing technology, health and safety standards, the decline of unions, and global and local competition, has washed away those old standbys.

Wonder why it's so hard for one-fifth of today's young people to find work that supports them? A large part of the answer can be read in the combination of dwindling jobs in, and rising barriers, to these seven industries:

Commercial fishing

Back in the 1980s, British Columbia's fishing industry was like a gold rush. Boats crewed by folks with little formal education could net a $1-million catch in a week, according to B.C. Seafood Alliance executive director, Christina Burridge. Japan's economy was booming, and Japan had an appetite for herring. Safety standards were low. Catch limits were high. And 15,000 people made their living from the coastal fishery.

Nearly all of that has changed. Salmon stocks plummeted. New training standards introduced in 2010 shut those without high literacy out of the industry. Safety standards rose, requiring investments that kept many boats off the water. Efforts to rebuild fish populations have limited fishermen to taking 30 per cent of returning fish instead of 80; this year may see a complete ban on fishing in the Fraser River. Even Japan's taste for imported herring ebbed. Margins for B.C.'s 5,700 remaining fishermen are low.

"Probably the biggest reason for failure [in the fisheries today] is business skills," said Burridge. "Anyone who lacks the education to run a business is going to find it much harder."

Forestry

Jonathan Lok is a relatively young guy, just 38 years old. But in a 20-year career in forestry, he's witnessed big changes. As a teenager without an education, he recalls, he logged in the summers and earned enough to pay his post-secondary tuition. Now the jobs are fewer, and few companies hire young, unproven keeners.

"The margins are so thin," he said. "You can't hire five guys and hope one works out anymore."

Twenty years ago, he said, B.C. forests were abundant in money, people and high-value, old-growth trees. Now, the owner-CEO of Strategic Forest Management says, his employees mainly harvest second-growth timber. It's more equipment-dependent, higher-skill work. Fewer people are needed.

While a few employers are still willing to take a risk, the conditions aren't likely to attract most of today's self-absorbed, self-indulgent "adulescents," as one author calls them. The work is in camp, with no wireless, early mornings, and often, long, cold, hard, wet work.

Manufacturing

B.C.'s manufacturing industry complains that its employers can't find enough people to hire, even at above-average wages. But they're not looking for Lavernes and Shirleys to sit by a conveyor belt, and put the tops on bottles between wisecracks. That popular sitcom was broadcast three decades ago and portrayed an era already past. Today's manufacturers are looking for people with technical skills learned at post-secondary school.

But it's up against stiff competition to hire the qualified. "That big sucking sound is Fort MacMurray," said Peter Jeffrey, the vice president of the Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters Association for B.C. "But then we have this mobility of labour problem. For the [very few] unskilled jobs that do exist, people in Vancouver don't seem to want to move to Prince George or Prince Rupert."

The military

Until the 1980s, you only needed to have completed Grade 8 to enlist in the Canadian Armed Forces. While the official requirement is still only Grade 10, Major Richard Langlois, spokesperson for the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group, noted that the forces receive 40,000 applications per year for just 4,500 positions. As a practical matter, most who are accepted have earned at least their high school diploma.

But Langlois stresses that the military isn't eager to be regarded as the country's employer of last resort. "The CAF remain interested in potential candidates who truly seek to pursue a career in the CAF," he told The Tyee Solutions Society, "rather than potential candidates uncertain of their future and seeking short-term employment."

Mining

City slickers might not realize that B.C. is home to nine metal mines, 10 coal mines, 35 industrial mineral mines, many smaller mines, plus nearly two dozen operations either in construction or in the permitting process. B.C. companies predict they'll need up to 20,000 new miners over the next decade. And as of last year, according to the BC Mining Association, miners earned an average of $98,200 a year.

The in-demand jobs include heavy equipment operators, mechanics, supervisors, mining and quarrying geologists, geochemists and geophysicists, drafting technologists and geological engineers.

The bad news for the unskilled: nearly all those jobs require post-secondary school.

For someone without an education the outlook is much bleaker. A few hundred mine jobs for unskilled labourers are scattered across the province. Average income for a full year of full-time work as a labourer can still reach $52,230. But in reality, that describes only one-quarter of such jobs.

Retail

Union wages once made retail sales work a viable full-time occupation for many. MP Pat Bell put himself through university working at the Woodward's camera counter for $12 an hour in the early 1970s. That's more than many department store workers earn today. Superstore was paying $23 an hour for cashiers back in the 1990s.

But those wage levels have been whittled back by years of de-unionizing.

Safeway and Save on Foods, both of which offered livable starting wages in the past, negotiated different (tiered) wages for new workers starting in 1997. The last unionized Starbucks bit the dust in B.C. in 2007. Zellars employees, formerly represented by United Food and Commercial Workers 1518, lost their contract in a B.C. Labour Relations Board hearing in 2012, when Target took over the lease. Ikea Richmond is working hard to tier its contract with its workers, offering some less than others.

The retail sector still represents the largest occupational group in B.C., but average pay for full-time, full-year work -- something only one in three clerks can hope for -- is only $35,468.

Most clerks, working part-time, earn even less. A job at Sears Personalised Gifts (Things Engraved) advertised on the Work BC website, for example, offers minimum wage -- $10.25 an hour -- and part-time hours. High school graduation is required, eliminating many of the most vulnerable young job candidates.

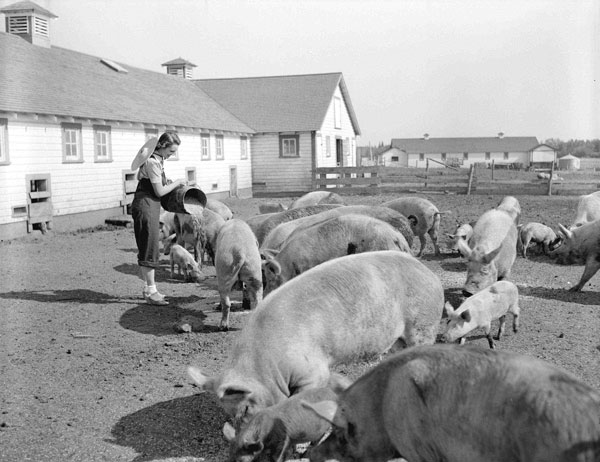

Agriculture

Just a couple of generations ago, farming is what Canadians did if they weren't doing something else. Most people who wanted a career in farming simply started as teenagers, either on their parents' farm or a close relative's, according to Reg Ens, executive director of the B.C. Agriculture Council. They learned on the job, putting in sweat to earn enough money eventually to buy their own parcel of land.

In 1931, one in three Canadians lived on a farm. Today, that number is one in 46, meaning that most young Canadians have little contact with farming, let alone a pathway to working in agriculture. Even for those with a family history in farming, the soaring cost of farmland and equipment has become a prohibitive barrier to entry for many.

Sure, agriculture offers entry-level jobs that require no post-secondary schooling in agriculture: fruit-picking or plant thinning for example. But they won't support a family, according to Reg Ens, executive director of the B.C. Agriculture Council. They're seasonal, and part-time.

To qualify for a career in agriculture, Ens said, some post-secondary school is usually necessary. Even a teenage, part-time assistant herdsmen who wants to keep his hand in dairy will usually need to take a certificate in nutrition and herd management, he noted.

In the past, most people who wanted a career in farming simply started farming as teenagers, either on their parents' farm or a close relative's. They learned on the job, putting in sweat to earn enough money eventually to buy their own parcel of land.

"It used to be enough that if I were a good production person, I could be a farmer," said Ens. "Now, you need to be a good businessperson. 'What crops do I produce? Where do I sell? Do I invest in food safety technology? How much debt do I take on? How do I negotiate my contracts?'"

As with most businesses, Ens said, many fail. No longer can farm labour be considered Canada's national fall-back career.

Tomorrow: When families fail to support children through the transition into adulthood, some experts argue that schools have the potential to step up. Four big ideas. ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: