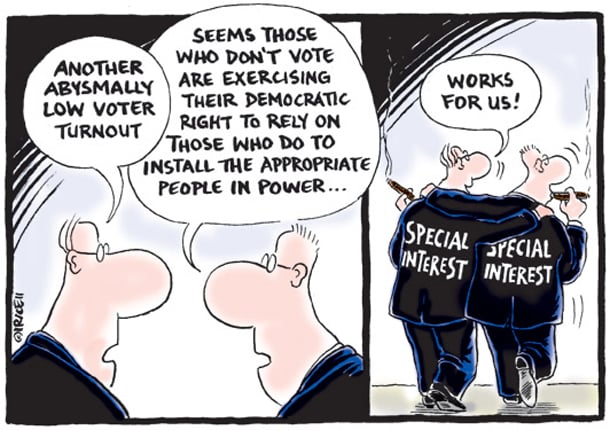

In the last federal election, considered by many commentators to be one of the most significant electoral upsets in recent Canadian history, more people chose not to vote than cast their ballot for any one political party. If Democratic Malaise had run a slate of candidates, it would now have a majority government.

The results are progressively lackluster as you work your way down to the local level of government. In the last B.C. election, only half of registered voters took the time to exercise that right. Last month, a dismal 35 per cent of Vancouver voters decided it was worth the trouble.

Who are these non-voters? Lazy, uninformed, and apathetic, the caricature of this silent plurality is of a class of people who do not participate in the rites of citizenship because they have no interest -- perhaps no respect -- for what it means to be a citizen.

But according to a new study by the Toronto-based think-tank, Samara, people are not born disengaged from the political process -- they are taught to tune out by a political system and government bureaucracy that has in turn tuned them out.

First of its kind

"Disengagement is a lot more complicated than people just not caring," says Alison Loat, co-founder and executive director of Samara. "In fact, it's the opposite: it suggests that people do care, but that the system hasn't been responsive to them."

The footwork for this study was conducted in August and October of this year when Samara researchers identified seven demographic groups who disproportionately view themselves as outsiders to the political system. These are lower-income Canadians, Francophone and English-speaking women living in Quebec, urban Aboriginal people, new Canadians, the less-educated, and those living in rural areas. By putting together a series of focus groups in cities and towns across the country, the think-tank was able to suss out the opinions, values, and attitudes of these characteristically disengaged groups on issues of politics and democracy.

In this respect, says Loat, the study is the first of its kind.

"Most research in the area of democratic participation focuses on elections and on the behavior of voters," she says. "As a result, we have a lot of discussion during the 40 days before and after an election about what did and didn't happen at the ballot box. But we spend no time talking about the 1,200 days in-between elections -- when people experience politics and democracy every single day."

Learned powerlessness

People do not form their views of the political process and establish their trust in the political system at large in the immediate run-up to an election, she says. According to the study, people are driven towards their disillusionment while waiting in line at a provincial employment office or in the middle of a frustrating telephone conversation with a disinterested city employee or while watching the contrived bickering of MPs, MLAs or city councilors on the nightly news.

Frequently failing to distinguish between different levels of government on the one hand and politicians and public servants on the other, these are perceived failures of a monolithic and nebulous "system." According to Loat these minor grievances can build up week after week until election day when an exhausted and demoralized voter simply decides to stay home.

Silver lining

If political disengagement isn't a character flaw, but the result of personal experience, the erosion of political participation in Canadian society is, at least in theory, reversible. This is the "silver lining" identified in the study. By making both political parties and public services more accountable, the Samara report argues, the political system will reap the dividends of higher participation rates.

On the one hand, says Loat, because the participants in the study put so much emphasis on their commonplace interactions with public service, a much higher priority should be placed on the provision of transparent and reliable public service. Correctly or not, she says, because public services and electoral politics are so frequently conflated by potential voters, improving results from the former will increase interest and participation in the latter.

Second, she says, political parties should spend less energy drawing out their respective political bases and opt for more inclusive campaigning strategies.

Not so simple

If only because it identifies a solution to what many political scientists see as the inevitable decline of voter participation across Canada and the rest of the democratic world, Samara's report offers a compelling diagnosis of the problem.

Compelling, say some, but not particularly convincing.

"I wouldn't trust what people say in a focus group," says Fred Cutler, a professor of political science at UBC. "When a human is asked why they did or didn't do something, they tend to come up with a reason."

In other words, while many of the participants in the Samara study consistently blamed their political inactivity on the inefficiency of government bureaucracy or the small-mindedness of politicians, the decision whether or not to participate may be the result of socialized behavior and disposition -- factors much more difficult to articulate or rationalize.

Take a committed voter. He or she is presumably aware that voting is almost guaranteed to have no effect on an electoral outcome, just as signing a petition is unlikely to sway a politician, and just as following closely the day-to-day happening on Parliament Hill is unlikely to effect what takes place there. Instead, Cutler argues, a politically active citizen is (and is likely to always remain) engaged because he or she derives some, often not totally rational, satisfaction from participation.

Likewise, though habitual non-voters may search for some concrete reason why they do not participate in political affairs -- for example, by pointing to all-too-common interaction with a government service that left them frustrated -- that may be because it's much more difficult for a person to explain why he or she simply doesn't care about something.

Generation Meh

Pointing to the gradual decline in political engagement across the democratic world since the mid-1980s, Cutler doesn't buy Samara's argument that this could be reversed with more efficient pubic service or more inclusive political parties.

Instead, he sees a much more profound shift in cultural attitudes from one generation to the next. Perhaps we are now more likely to take our democratic institutions for granted. Perhaps our schools and popular culture no longer espouse the virtues of electoral participation and political literacy as vociferously as they once did. Perhaps we as a society have become more resistant to behavioral socialization and, to put a positive spin on things, we are more likely to assess the value of things for ourselves.

"I wouldn't necessarily call that dire -- I'd call it inevitable," says Cutler. "We should be amazed that as many people still take the time to vote as they do."

Healthy indifference

When we bemoan the decline of Canadian voter turnout, says Cutler, we are referring to a drop from the mid-century average of roughly 75 per cent to the current slump of around 60 per cent.

"We're only talking about 1 in 6 voters who might have voted previously out of a sense of obligation and duty, not voting now," he says. And that is not necessarily a bad thing. While people now seem less inclined to actually vote, there is less evidence to suggest that Canadian society as a whole is less politically informed. Perhaps, says Cutler, we now tend to vote -- or not vote -- for better reasons.

"Half a century ago, a person would often vote in a way that was almost assumed by their ethnic background, their class position, their religion," he says. "Nowadays, particularly among the younger generation, people feel like if they don't understand or if they don't want to invest the time to distinguish between their options on the ballot, then not voting is actually the right thing to do."

Taking the democracy's temperature

If turnout figures are not the most reliable metric by which to measure the health of our democracy, Samara is hoping to develop a working alternative within two years. With a team of 24 academics, the think tank plans to produce a democratic health index, a kind of GDP figure for civil society, that will assess the state of Canadian democracy between election cycles.

"We want it to assess not only how parliament and parties work, but also media and public discourse, citizens and their behavior and perceptions," says Alison Loat.

Loat says she hopes the first index will be ready in 2013. Maybe just in time for the next B.C. election. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: