[Editor's note: This finishes our series built around Patrick Condon's new book Seven Rules for Sustainable Communities: Design Strategies for the Post Carbon World. Today a Tyee exclusive: Condon applies his principles to crafting a sustainable future for BC's Lower Mainland.]

In 2006 the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change declared that scientific evidence was undeniable: climate change was real, climate change was human induced, climate change was already happening, and if global temperatures could not be stabilized, global ecological systems would be critically disrupted for millennia and millions might die.

The governments of every nation on the planet sent their own selected and respected scientific representatives to participate in the IPCC deliberations. A unanimous agreement from every one of the planet's governments on anything is more than unprecedented. It is incredible. You would think this extraordinary agreement would prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that we have history's first true global crisis on our hands. Inexplicably, despite this astonishing unanimity, many citizens and even some elected officials remain sceptical. If you are one of them then nothing I can say will be more persuasive.

If, on the other hand, you are a part of this global consensus, then you likely want to do something about it -- but are unsure what. Fortunately, we who live on this special corner of the planet have more power to attack this problem than almost anyone else. Here is why.

Why Lower Mainland residents can save the planet

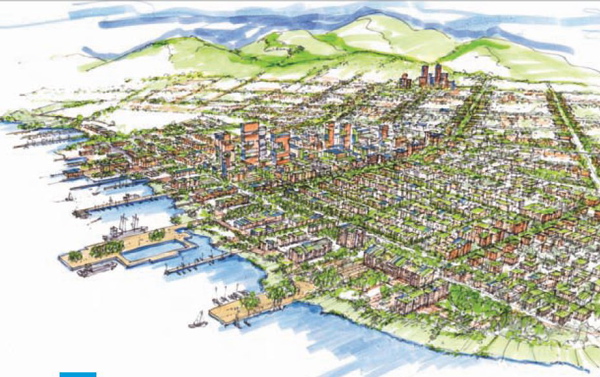

Right now the Lower Mainland of British Columbia leads any other region in both Canada and the United States in reversing the rush to global climate collapse. This is because more people in our region prefer to live in walkable, diverse, jobs rich, dense neighbourhoods, than ever before. And as the distance between people, jobs, recreation, and education shrinks so too does our individual production of greenhouse gases.

The region is now internationally famous for defying what had been thought of as ironclad immutable laws of North American urban development: that people always prefer lower density -- well they don't; that as density increases crime increases -- well it doesn't; that if you add more housing units you can count on more traffic -- well the opposite is true; that people will always drive the car if they have a choice -- well no, not always.

Citizens and officials in our region thus have a unique opportunity: we can to continue to lead North America to a sustainable future. And since Asia, China in particular, is constantly copying North American models for urban development, our positive influence can extend across the globe as well.

What is special about our leadership is that we have accomplished all of this, not primarily through investing in new energy systems or transportation infrastructure, but by the opposite. It came about not through what we did but by what we did not do.

We did not overbuild a freeway system (our region has fewer freeway miles per capita than any other major North American metropolitan region), we did not allow building on our agricultural lands, we did not allow building on our mountain sides, and we did not clear vast portions of our urban landscapes for misguided "urban renewal projects". Instead, for the most part, we built on what we had, gradually adding more and more houses and jobs to our existing urban footprint. As we capitalized on the investments of previous generations -- in transit arterials, in jobs areas, in bridges and serviced residential areas -- we lightened our tax burden while we reduced our average impact on the planet, at least in comparison to the exaggerated demands of the folks in sprawling Houston and Calgary.

The constraint on our land supply and the efficient use of our infrastructure has not been without its costs. Many in our region decry the consequences that they say accrue from our constraints: traffic congestion south of the Fraser and high home costs in Vancouver to name but two. Certainly both of these problems degrade our quality of life, undermine social equity, and impede the economic vigour of our region. Yet congestion and high land prices have also had a positive consequence. Together they created a market for higher density infill housing in our cities, assisted in the gradual distribution of job sites throughout the region, and precipitated the appearance of our now very popular high rise residential lifestyle. Our new higher density residential life style, so attractive to so many, could not have competed if our market had been flooded by low cost lands. Had we undercut the market for density by opening up protected and distant lands for development, and by building more freeways to access these lands, this region would resemble Atlanta by now: a dead downtown, traffic choked shopping malls, and a housing market dominated by still unaffordable homes located very far from services. Would we trade for this?

So where do we go from here? Certainly a sustainable region is one that is sustainable in many ways, social, economic, and ecological; but for the next generation of citizens and their elected officials the opportunity to move to a carbon zero region is paramount. It is also probable that in so doing we will enhance social equity and economic vigour, as evidence indicates that so many of our social and economic pathologies -- from obesity, to transportation expenses that are a crushing burden to middle class families, to the impossible burdens to the corporate and private taxpayer for maintaining an inefficient infrastructure structured around the car -- are consequent to our over-reliance on carbon spewing vehicles, and the overextended urban infrastructure that carbon combustion always spawns. And we are wise to get there by drawing on the four lessons drawn from our past success.

FOUR LESSONS ALREADY PROVEN IN THE LOWER MAINLAND:

Lesson 1. Do more with less. Because we did more with less we now use about half as much carbon per person than the average Calgarian. We can continue to extract many more efficiencies out of the machinery of our region's infrastructure and the land uses this infrastructure serves.

Lesson 2. Become more complete. Many of our past and hopefully our future efficiencies accrue from making "nearness" the rule. Our lives become more convenient as what we need comes closer to us. Our demands for travel are already decreasing as our cities diversify. Our region was the only region in Canada where average commute times to work decreased between 1990 and 2000, largely as a result of new downtown living bringing homes close to jobs. As things come closer our addiction to carbon becomes much easier to kick.

Lesson 3. Make living light on the planet an attractive lifestyle choice. In Vancouver, higher density living was not sold as affordable housing, or as a way to save the planet, but as a way to make your life more complete. People in our region are now flooding to districts that would have been dismissed as "too crowded" only a generation ago. For these new residents, crowds are what make urban life worth living. Every effort should be made to accelerate this urban transformation throughout the region. As the excitement of being in close exchange with other citizens and services becomes more widespread, the benefit is ever increasing material and energy efficiency. To cite only one example of this synergy, district heating systems become economically viable to provide only beyond a certain density threshold. Once this threshold is reached the energy required to heat and cool a building can be cut by over half while replacing carbon sources (natural gas) to renewables (hydro and wind).

Lesson 4. Work with, not against, the structure of the region. Our region composed primarily of relatively low-density streetcar city neighbourhoods. Our success in promoting downtown high rises carries with it the risk of us presuming that high-rise living is the answer to all of our problems. But with many hundreds of underutilized kilometers of former streetcar and interurban corridors in our region and almost a thousand square kilometers of urbanized low density lands, a strategy based on towers, while appropriate for downtown Vancouver seems wrong for most other places.

The legacy of our streetcar city pattern is a dispersed, but not impossibly sprawling, region. It is a pattern that once supported a mode of living that required very little carbon to sustain it, within districts of medium density where ground oriented housing and services predominated. We need to understand this inherent structure and work with it, not against it. To fail to do so will result in a waste of the investments made by previous generations and provoke anguish in the hearts of current residents -- residents who see their communities too radically changed.

We can already see evidence of the organic revival of this form in Vancouver along Main Street, Fourth Avenue and Broadway in Kitsilano, and Dunbar Street. On the other hand we also see a failure to recognize how inappropriate it can be to insert grossly out of scale projects into the fabric of the city in the current proposals for massive high rise projects on all four corners of Cambie and Marine Drive Skytrain station area.

So with this golden opportunity to help save the planet before us, what can be our roadmap? Firstly a caveat: we need to continue what is an incessant and evolving debate about the future of our region, a conversation of unprecedented quality, the likes of which is unknown in most other North American urban regions. So debate is never closed and the answers never definitive. Thus the rules provided below are intended only to energize that debate. Here then we offer seven simple rules for a sustainable region, a proposed roadmap for global leadership merely in the hope of furthering that debate.

SEVEN RULES FOR A SUSTAINABLE REGION:

Rule 1. Restore the Streetcar City. Our regional transportation investments are still driven by 1960s era thinking. These investments have prioritized the long trip over the short trip, with too much money allocated for damaging freeway expansions and for impossibly expensive Skytrain expansions, and not enough to support complete community growth. In order to meet our 2050 targets for carbon reduction we must shift from a region where 80 per cent of all trips are by car to one where 80 per cent of all trips are by carbon zero electrified transit, walking and biking. This is only conceivable if our communities become much more complete.

While this seems daunting, this is already the situation in Copenhagen, a city not unlike ours in extent and in climate. The secret, as Copenhagen makes clear, is to bring what we want closer to us rather than connect it with impossibly expensive and ultimately unsustainable infrastructure.

Rule 2. Design around the five minute walk. Walking is the crucial part of this Streetcar City strategy. Electrified transit that serves complete communities is best understood as a means to extend what is essentially a walk trip. With walking (and its ally biking) at the core of our day to day activity, our energy demands for movement shrink to zero while our health dramatically improves. Putting our immediate needs and frequent transit within a five minute walk is the crucial requirement for this to work.

Rule 3. Provide a diversity of affordable house types. Complete communities are not possible if affordable housing cannot be found. Given that housing is provided as a market commodity in our region ways must be found to even the distribution of affordable housing. The recent legalization of formerly "illegal suites" throughout our region is a giant step in the right direction. Similarly significant is the recent legalization of "lane houses" throughout the City of Vancouver, making Vancouver the first city in North America to do so. The next and even more important step will be to dramatically increase the production of housing units along the regions arterials, a process that will provide affordable entry level housing to many thousands of individuals and families, while at the same time bringing urban amenities and lifestyle quality to the regions often underutilized and parking lot dominated suburban strips.

Rule 4. Preserve and create an interconnected network of transit arterials. In keeping with a vision to humanize and urbanize the regions vast and existing network of arterial streets, it makes perfect sense to favour a transit network over the current "hub and spoke" system of "big pipe" transit systems. Over investment in Skytrain systems sucks the life out of surrounding arterials while putting far too much pressure on certain big pipe movement corridors. The City of Vancouver is already projecting massive increases of traffic and density along the Broadway Corridor out to UBC consequent to an assumed subway line along this route.

The result would be the Vancouver version of Los Angeles' Wilshire Boulevard, with towers marching inexorably across the landscape while corridors to the south remain under-served and urbanistically impoverished. This big pipe thinking has been undercut by recent advances in sustainability theory. Generally speaking, distributed systems, or networks, are far more resilient than concentrated big pipe systems. This is as true for traffic movement systems as it is in the construction of computer networks. In this respect, the most hopeful development in our region is the emergence of the "frequent transit network" strategy as a new and fundamental element of the current regional growth strategy document from the Vancouver Metro regional planning agency.

Rule 5. Make jobs-rich corridors near every home. Given the nature of work in our region, and the dramatic increase in non-manufacturing jobs (financial services, health care, media, education, consulting, etc.) it is sensible to promote an even distribution of those jobs throughout the transportation matrix. This suggests a relaxing of the original "regional town centres" strategy embodied in the 1995 "Livable Region Strategic Plan". This laudable plan assumed that jobs would concentrate in the regional town centers. They did not. On the other hand they did not land in remote parts of the region attached to distant freeway umbilicus like they did in so many other North American urban regions. Largely they are still close to the regions network of transit arterials (albeit often badly designed for transit access). Regional policy can recognize this dispersal as a good thing, if it is incorporated into the frequent transit network strategy currently emerging in the regional plan.

Rule 6. Restore and protect green networks for water and other living things. Streetcar City densities are compatible with bringing natural systems to our doorsteps. We currently spend too much money on roads that perform well as car sewers but perform miserably in most other ways. Simple strategies exist for linking natural systems into the design of street systems, strategies that work with not against nature and save the taxpayer dollar at the same time. In this context there are notable but all too slow indications of progress. The East Clayton project in Surrey and the UniverCity project at SFU Burnaby are

important North American precedents for sustainable streets linked to natural areas and parks. As our region rebuilds the streetcar city form there will be a wealth of new space opened up on existing rights of way, no longer so completely overwhelmed by the car, to continue to retrofit our public realm streets for green functionality.

Rule 7. Start building closed loop energy recycling systems. Walkable Streetcar City neighbourhoods are also easy and cheap to heat and cool. At Streetcar City density it becomes practical to incorporate district heating systems and systems to extract otherwise lost energy from wastewater. Coupled with other advances that are most practical at streetcar city densities (biological digestion of household and sanitary "wastes" for energy, to cite only one more example) it would seem that a zero carbon region might be almost within reach.

Do all of this for the kids.

These seven rules are intended to provoke and extend a conversation in our region about how to preserve the gains we have made in the past, and to accelerate them in the future. Climate change is a crisis. This crisis will increasingly define the lives of everyone on the planet. This author makes no claim to absolute prescience in these matters. My own efforts are motivated not by pedantic arrogance but rather by desperation. It is heartbreaking to anticipate the extreme travails that will be experienced in the not too distant future by my, and by your, children and grandchildren -- and by all of the world's unborn.

The science-based projections of the nearly inevitable outcomes of inaction are horrifying. It is simply too painful to be silent. The good news, the very good news, is that we here in this region can do something about it, and improve our quality of life in the process. Together we are making advances that defy standard assumptions about how cities grow, and what people do and do not want from them; but there is still much to be anxious about. Recent regional transportation efforts, the ill advised "Gateway" freeway building project and funding travails and lack of clear direction for our regional transit agency, Translink, indicate that we may have lost our way.

It is therefore up to a new generation of citizens, professionals, and elected officials to coalesce around a common vision for the future -- a common vision deeply grounded in the pioneering efforts of the previous generation, and in the tangible physical realities of the place where we live. These seven rules, and the "Streetcar City" principle to which they all somehow connect, are my own personal best shot at such a vision. There are many others. Let the debate continue. But let us also start building the sustainable region right away. Let's start Monday. There is no time to lose. ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: