[Editor's note: This is the sixth of eight excerpts from Patrick Condon's new book Seven Rules for Sustainable Communities: Design Strategies for the Post Carbon World. This series, running Wednesdays and Thursdays for four weeks, offers just a sampling of Condon's vital guide for green planning; interested readers are encouraged to seek out the book.]

Where we live is the other side of the jobs/housing relationship discussed earlier. In this chapter, we look more carefully at how the types of houses we live in and their arrangement on the parcel, on the block and in the district influence the sustainability of the region and the per capita production of greenhouse gas in particular.

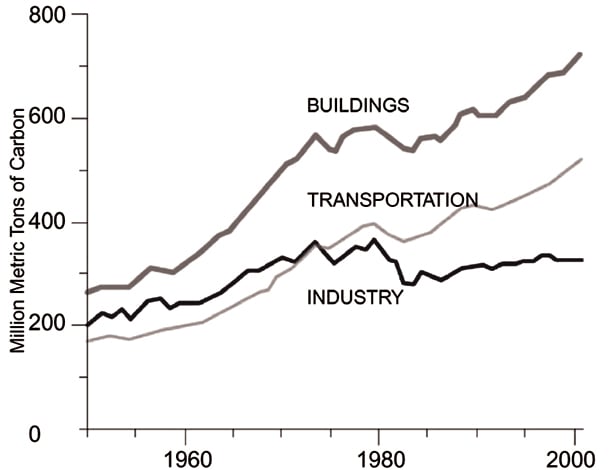

In both the United States and Canada, buildings generate a larger share of GHG consequences than any other sector -- larger than the transportation sector, larger than the industrial sector. However, the relative contribution of buildings to the total regional GHG produced varies from one part of North America to another.

This is due to a few basic factors: (1) the more or less stringent building energy-performance standards in force; (2) the source of energy used for building heating and cooling and (3) the severity of the climate.

In states and provinces where the climate is quite extreme and coal is used to produce electrical energy, and where the fuel for non-electric furnaces is typically oil, GHG production per square foot of built space will be relatively high. In the United States, the state of Ohio fits that bill. Oil-fired heaters and coal-fired electrical generation provide the bulk of the energy used by buildings there.

In milder climates, where electrical energy comes from hydro, electric or nuclear power, and where heating is either from electric or from natural gas, GHG production per square foot of built space will be much lower.

The Canadian West and the U.S. Pacific Northwest fit that bill. Due to the ready availability of hydroelectric power and natural gas, the GHG production per square foot of built space is relatively low. Thus, in Seattle, Portland and Vancouver, transportation accounts for a higher percentage of total metro area GHG than do buildings.

Different regions, different priorities

These basic energy differences will influence how various regions approach the GHG reduction challenge. For some, buildings might take priority; for others, it might be transportation. In either case, the arrangement of buildings on the land, and how one moves from one to the other, will be the crucial starting point for analysis.

Residential land uses typically consume between 70 and 85 per cent of all developed North American metropolitan lands. How these lands are utilized and configured is likely the most crucial physical factor for determining the social, economic and social sustainability of the region. Current policies have worked at cross purposes with basic social, economic and ecological sustainability goals.

The homogeneity of our residential landscapes -- in many cases, fostering a residential monoculture that covers whole municipalities -- has undercut ecological sustainability in two ways.

First, as discussed earlier, zoning and subdivision regulations make it much more difficult to supply affordable housing near work sites. Second, zoning and subdivision regulations ensure that GHG impacts from buildings will be unreasonably high (by favouring building types that are inherently expensive to heat and cool), and in arrangements that gain none of the potential benefits of adjacency to other dwelling units.

Zoning has been used, consciously or unconsciously, as a tool to undercut social sustainability. It does so by enforcing social inequity.

Zoning regulations do one thing well. They ensure that large districts are covered by residential lots of one size and that these lots allow only one tenure type. Neighbourhoods regulated this way are inherently exclusionary and thus defy the most elemental definition of a sustainable society.

Narrow neighbourhoods

Proscriptive zoning policies lead naturally to neighbourhoods occupied by a very narrow demographic band, a narrow range of ages, a narrow range of incomes and a narrow range of family types.

Such monocultural neighbourhoods also undercut economic sustainability; they are difficult, if not impossible, to adapt to changing future circumstances. Most metropolitan areas have dedicated the lion's share of their lands to a housing demographic that is rapidly disappearing: two-parent families with more than two children.

Three- and four-bedroom houses, now increasingly occupied by one or two individuals -- often aging empty nesters with more than one empty bedroom -- dominate many first- and second-ring suburbs. Meanwhile, young singles and couples are likely in search of adequate and affordable places to live in what might be a highly competitive housing market, while all those bedrooms sit empty.

Our regulations ensure this imbalance and, because zoning is so difficult to change once set in place, make it almost impossible to fix.

Given that current policies are counterproductive, it may be reasonable to start over with an opposite set of policies. Where previously we insisted on uniform parcel sizes, perhaps we should insist on a diversity of parcel sizes that would lead inevitably to a diversity of housing types.

Where previously we insisted on one tenure type covering vast areas, perhaps we should insist on multiple tenure types on every block. Where once we insisted that commercial and residential uses be separated, perhaps we should bar single-use subdivisions.

Where once we banned rental units from the neighbourhood, perhaps we should find policy tools that could ensure their presence. The strategies listed below for building and arranging sustainable housing provide a starting point for citizens and officials to assemble such a suite of policy tools.

Build and adapt neighbourhoods for all ages and incomes

In U.S. and Canadian cities, zoning has been used as a tool of separation rather than integration. From the social perspective, zoning by density categories is especially heinous, as this separates families by income and thus by class.

Census dates confirm an almost one-to-one relationship between a zoning designation for a particular district and a narrow band of incomes exhibited by the families living therein. Discriminatory impulses play themselves out in the process of determining new zoning status for adjacent areas, with many homeowners extremely reluctant to see a designation applied nearby that would allow families of lesser means to purchase a home.

Prior to the 1940s, districts typically had more than one house and tenure type and sometimes a wild profusion of variety. Maple Avenue in Cambridge, Mass., exhibits a level of income, tenure and house type variety that was banished from virtually all neighbourhoods built after the Second World War.

On Maple Avenue, you can still find a one-, two- or three-bedroom apartment. You can also find a 16-room house on four floors. The income demographic on the street is tremendously wide and provides residents of all ages and incomes a place to live, residents who can fill the jobs in the district and age in one place should they wish.

But the success of Maple Avenue must not be oversimplified. It is not only that the street contains a variety of tenure types; it is also that the buildings make, for all their differences, a unified but diverse visual ensemble.

Porches and protruding eves abound, horizontal clapboards predominate, floor heights are common from one lot to the next, and each house takes pains to acknowledge the importance of the street architecturally.

Vancouver's policy shift

Successful places must be successful in both the quantitative realm (tenure types, numbers, rents, sizes) and the qualitative (architectural details, massing, materials, sensitivity to historical context).

Policy changes are needed whereby all newly developed or renewed and retrofitted areas would be required to include a wide variety of house types. These policies must go beyond Massachusetts' Chapter 40B law, which requires affordable housing somewhere in town but does not govern where, to urban design policies that are applied at the much finer grain scale of the neighbourhood.

Vancouver provides a good model for adding housing diversity to existing residential districts, and in two different ways: (1) through building new higher density, low-rise buildings that are compatible with lower density neighbours and (2) by learning how to convert existing single-family homes into multiple dwelling structures.

In the 10 years between 1990 and 2000, 40,000 new residents found homes in the city's older single-family and low-rise residential neighbourhoods, a number equal to the number accommodated in downtown towers.

During this period, Vancouver architects and city planners learned that residents do not object to added density so much as they do to the feel and appearance of density. Not wanting to engender unnecessary resistance, architects learned how to design buildings that looked and felt like the low-density buildings next door.

Large facades were broken into pieces scaled to the roof, dormer, window and facade forms of nearby residences. Roof pitches of new buildings were steeply sloped and highly articulated to mitigate four-storey heights. Building fronts were provided with as many individual entrances as possible for the same reason.

The example proves that NIMBY responses are not knee-jerk reactions to density per se, but understandable reactions to disrupting the unified and comforting qualities of many fine single-family home areas.

'Illegal suites'

The second effective strategy for gradually adding density to existing single-family home areas has been through converting single-family homes to structures with multiple dwelling units.

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, because of the way North American cities grew, and given the influence of the baby boom demographic in particular, most U.S. and Canadian metropolitan areas are oversupplied with single-family homes built for large families but now occupied by only one or two people. Vancouver is no exception but has found a way to occupy those empty bedrooms.

Since the 1970s, housing in Vancouver has become increasingly expensive. With rents rising, some homeowners decided to convert part of their homes for rental to capitalize on this demand.

Typically, these "illegal suites," as they are known, were located in the basements of Vancouver's most common house type, the bungalow. The bungalows of Vancouver have a peculiar characteristic. Because of unusually wet soil conditions, the slab elevation of the home is very shallow, leaving the basement floor only two to three feet below grade.

Thus, tens of thousands of basements in Vancouver have full-size windows and a basement floor that can be reached from the outside at grade or with just a few steps down. These rental units were built without the benefit of code inspection, so they varied wildly in their execution.

Area residents, and thus their elected officials and code enforcement officers, knew of this trend. But rather than closing down these units, as might be expected in U.S. cities, the City of Vancouver adopted a characteristically Canadian response to this emerging trend.

Breaking the law

The issue of illegal suites came up for debate in council on many occasions, but for every homeowner who complained, there was a renter or a rental-housing advocate who argued that these units were necessary to avert a housing crisis. Thus no action was taken; but the conversation was prolonged, seemingly indefinitely.

The supply of these units gradually grew until there were tens of thousands. During this same period, the cost of single-family homes more than tripled in real terms. This influenced the behavior of individuals and families seeking not a place to rent but a place to buy.

Since average family income had more or less stagnated during these decades, single-family homes, once affordable to the middle class, were now out of reach -- unless an income stream was available to help support the mortgage costs.

This income stream was the illegal secondary suite. Fully one third of the monthly cost of the mortgage could be met by the rent from the suite, making it at least possible for the schoolteacher, or the merchant, or the bus driver to own a detached home.

Suddenly, the entire market shifted. Real estate agents would show a home paying specific attention to an existing suite or a space suitable for a suite, providing probable rents, and helping potential buyers calculate what effect this money would have on their monthly payments.

In time, reaching well into the 1990s, the vast majority of home buyers were looking for homes where they could also be landlords. During the 1980s and 1990s, proposals to legalize these suites were occasionally floated.

Longtime area residents who owned their homes, and who therefore felt none of the financial pressures that weighed on younger home buyers, usually opposed these proposals. Thus, proposals for legalizing secondary suites died during these decades.

The new majority

It was not until the first decade of the new millennium that a citywide blanket allowance for the creation of new secondary suites in single-family homes passed city council. By this time, well over half of single-family homes in the city had already been converted. Thus, voting homeowners were no longer opposed to this new policy, since they already depended on it.

Vancouver has been changed, for the better, by secondary suites. Tens of thousands of affordable new rental units have been created, and a synergy between middle- and upper-middle-class families and lower-middle-class, blue collar and service sector-employed families has emerged: an economic ecology of the parcel, where neither the landlord nor the tenant could afford to live there without the other.

In time, the creation of suites was legalized, as was the separation of existing single-family homes into two, creating a legal duplex where each side was available for purchase. In some areas, the regulations allow the conversion of single-family bungalow structures into three-unit condominium structures, providing that the original structure is preserved and the architectural quality of additions conforms architecturally to the host structure.

Although certain cities, such as Vancouver, have managed to attain a relatively high degree of diversity, such conditions often arise more from organic and fortuitous circumstances than from a systematic approach to the issue. When consciously planning for diversity in new communities, a robust methodology is required.

Using demographics

One such technique that can be implemented at the project scale is to directly use the income and family type demographics of a specific area to generate the appropriate palette of building and tenure types for a given neighbourhood.

The quantitative portion of this undertaking (income and demographics) can be readily attained through census data. Once obtained, this information can be the major driver in selecting the building and tenure types for a particular neighbourhood development.

In doing so, the project could and would be a physical manifestation of the larger demographic pattern particular to a specific area.

The Pringle Creek Community in Salem, Ore., serves as a case in point. This project, developed by Sustainable Development Inc., is grounded in a rigorous set of guiding principles that integrate green building, energy efficiency and environmental responsibility.

One major goal was to make Pringle Creek "look like Salem," meaning to include all of the types of families that are found in that city. Toward this end, the design teams conducted an in-depth analysis of the demographic patterns of the Salem region.

This required an understanding of the types of household in the region -- single-parent families, extended families, two-children families and so forth -- and their respective average incomes and space needs. Given the direct relationship between spatial requirements and the costs of construction, this information was supplemented by the hard data concerning housing and building.

This hard data included the average price of homes throughout Salem and the square foot costs associated with constructing certain building types. This helped the design team understand the economic, social and construction context within which the project was to be built, methodically bringing together all the elements required to make development decisions in keeping with their housing diversity goal.

With this information in hand, the design team organized the community as a microcosm of the larger Salem context. The number and type of dwellings chosen were directly correlated to the demographic patterns analyzed -- each home calibrated in size and costs to the incomes of each type of household to be accommodated. The result is a mosaic of people and places in homes that they can afford and that suit their family needs.

The housing crisis

Housing in North America has reached a crisis point where homogenous communities discriminate against buyers not by race but by income (which in some areas amounts to the same thing).

From a social equity perspective, it is not an overstatement to suggest that this apparently intentional breach of the principle of fair play and opportunity is a disgrace of major magnitude and must not stand. As a practical matter, it is equally odious.

The radical segregation of our cities and towns by class, often assigning entire towns for exclusive occupation by one income group and another town far distant for everyone of a lower income group, guarantees that our transportation woes will continue indefinitely.

Legislation like Massachusetts Chapter 40B is a big step in the right direction. Upheld many times in the face of constitutional challenges and political assaults, it clears a path for redress.

But much remains to be done. Chapter 40B, and similar narrowly executed policies, have not yet integrated communities in an organic, holistic way.

It helps little in rationalizing our urban landscapes for walking and transit if worker housing continues to be placed in locations that are only serviceable by car. Fortunately, models for suburban and urban retrofit, tools for planning and designing more equitable communities, are emerging.

A better landscape

The United States is expected to add 130 million new residents in the next 30 years. Canada is expected to grow at a similar rate.

Where and how are these people to be housed? With proper local and regional strategies in place, these new families can be the instrument for a vastly more equitable, efficient and low-carbon urban landscape.

This is enough building mass to create thousands of new walkable centres or to be the vehicle for retrofitting presently car-oriented strip commercial corridors.

No new opportunity should be wasted in deploying this growth strategically in an integrated way. There is not a moment to lose.

Next Wednesday: Rule 6 - Create a linked system of natural areas and parks. ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: