Joseph Mairs has been dead nearly a century. This Sunday people will gather beside his grave in Ladysmith cemetery to lay a wreath and send a wake-up call. The social contract hard won by B.C.'s labour movement decades ago, they say, is fast unraveling. Getting it back will take determination and sacrifice - the kind of grit shown by Mairs, who died at the age of 21, imprisoned for his role in the "Big Strike" by Vancouver Island miners between 1912 and 1914.

The memorial event, to be held from 11 a.m. to noon this Sunday, was introduced as an annual program by the Nanaimo, Duncan and District Labour Council last year. The organizer is Alastair Haythornthwaite of the International Association of Machinists.

Haythornthwaite sees large and powerful companies and the government backing away from the unwritten social contract requiring them to safeguard the well-being of workers "on the front line" and society as a whole.

"People in BC are getting in a situation where that contract--formed after World War II when it was agreed to look after members of the military who had gone off to fight--is being broken," said Haythornthwaite.

"To turn that situation around, we need the spirit of self-sacrifice. It comes down to the spirit of self-sacrifice versus the spirit of opportunism where people advance themselves rather than others.

"These people in the strike back before the Great War were up against the most powerful odds. As with the labor movement standing up to business and government today, (coal-mine baron James) Dunsmuir was backed by the provincial government, backed by the federal government. Only through the self-sacrifice of the miners was there any hope to change the situation."

Haythornthwaite said that come wind, rain, snow or sleet, the wreath-laying will take place at the cairn of Joseph Mairs in Ladysmith Cemetery almost 90 years to the day since the young miner died in Oakalla Prison Jan. 20, 1914.

Mile-long funeral procession

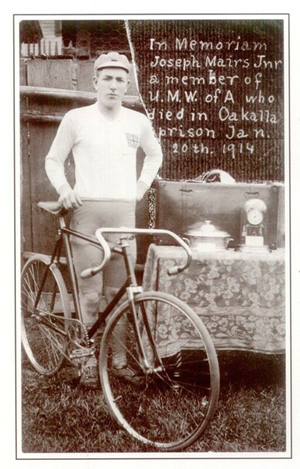

Until now largely overlooked in B.C. labour history, Mairs died from inadequate medical attention in prison less than three months into a 16-month sentence for taking part in what was then legally called "an unlawful assembly" - one of the mass demonstrations being staged against efforts to break the on-going strike. When Mairs was buried, several hundred people attended his mile-long funeral procession and hundreds bought a card showing a photograph of the prize-winning cyclist to raise money for the memorial. The small monument is engraved with the words: "A martyr to a noble cause - the emancipation of his fellow man."

At the time, in the Legislature, a left-wing MLA laid the blame for Mairs' lingering death squarely at the feet of Premier Sir Richard McBride and the province's prison system.

Mairs was born in Scotland and likely came to Canada with his parents sometime between 1908 and 1912. He and his father went to work at the Extension Colliery run by Canadian Collieries (Dunsmuir) Ltd. at Ladysmith, on southern Vancouver Island.

The Dunsmuir part of the company name referred first to Robert Dunsmuir and then to his son James who inherited his father's coal mines on Vancouver Island when Dunsmuir senior died in 1889. The mines made the younger man the richest man in BC but little credit was given to the workers on whose backs the empire was built, and James Dunsmuir is quoted as telling the 1903 Royal Commission on Labour Unrest he'd rather close mines than be told how to deal with the men who worked them.

Asked whether it had occurred to him that corresponding obligations came with enormous wealth, Dunsmuir is cited as replying: "No, sir. Not from my standpoint it doesn't."

Strikers herded into camps

Dunsmuir had sold off most of his operations by early 1910 but the cruelly-repressive regime he helped foster in the mining industry continued in both Canada and the United States. The Extension Colliery and the nearby Union Mine became the flash-point for the Big Miners' Strike in mid-September 1912 when two United Mine Workers of America activists were summarily fired - allegedly for reporting gas in one of the mines.

The miners responded by declaring a one-day "holiday" and demanding that Canadian Collieries recognize the union, already at the centre of a massive battle with the mining industry in the United States.

Instead, the company locked out the workers, precipitating a strike which would not be ended by the miners until August 1914, after the outbreak of World War I and two months after the union withdrew its financial support following the bloody Ludlow Massacre of April 20, 1914 in the United States.

The aptly-named slaughter by the National Guard took place at the mining-strike tent city of Ludlow, 18 miles north of Trinidad, Colorado, starting with machine-gunners opening fire on the canvas encampment. Thirteen people were shot dead in that part of the incident but it did not end there. When night descended, the militia moved in and set fire to the tents, thinking that the occupants had fled. They evidently did not know that two women and 11 children had been hiding beneath a cot and had not escaped with the other strikers. They all died but no charges were ever laid against the guardsmen.

That was three months to the day after Mairs died. By May 1913 the strike on Vancouver Island had spread to the other coal mines, with the mine owners and the government turning to strikebreakers and increasing force to try to keep the mines open.

"Nanaimo and Ladysmith came under what amounted to military occupation for almost a year, with hundreds of residents herded into camps fenced in by barbed wire," reports Haythornthwaite.

"When Canadian Collieries evicted miners and their families from company homes and imported strikebreakers," says an entry to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography by Simon Fraser University labor lecturer Mark Leier, "union miners organized strong picket lines. The province sent in constables, and by August scuffles were breaking out."

Guilty plea a death sentence

According to report, on Aug 13, 1913, the strikers virtually took over Nanaimo. That was too much for the provincial government, who promptly sent in a shipload of militia a day or two later. Mairs was arrested along with 40 miners and others in a further demonstration of civil unrest deemed a riot in the nearby community of Ladysmith Aug. 15, which involved stone-throwing, window-smashing and other resistance and protest action. He and more than 200 strikers from the Nanaimo and Ladysmith area were then held in custody without bail pending trial.

Mairs, who was suffering from a pre-existing internal health condition from lesions from a previous encounter with tuberculosis, chose a speedy trial by judge alone and pleaded guilty in the hope of receiving a short sentence.

Documentation shows though that on Oct. 23, after the rioters had spent more than two months in jail, provincial judge Frederic William Howay sentenced Mairs and 22 others not seen as either leaders or as just having been on the periphery of the Ladysmith riot a further 10 months' jail -- for a total of a year's imprisonment. He also fined them $100 for being involved in the demonstration.

"Mairs was taken to Oakalla Prison Farm, where he was put to work clearing land," says the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. "Described by the warden as a 'good, quiet prisoner', he was transferred to the prison's kitchen on 12 Jan. 1914."

The transfer came too late. Two days later, Mairs complained of severe stomach cramps and was given hot-mustard pills, cod-liver oil and salts by an inmate who served as a medical attendant. The severe medication did not help and Mairs' condition worsened. After a further four days, the visiting prison doctor diagnosed him as having "acute indigestion", in spite of being told that Mairs had had surgery in Glasgow in 1907 or 1908 for a bowel obstruction.

The doctor later testified that Mairs did not complain of being in pain though. He merely prescribed "a stomach medicine" and then the next day administered an enema. Mairs died the day after that, Jan. 20.

"An autopsy revealed that he (had) had tuberculosis of the intestine," says the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. "Obstructed by adhesions and undoubtedly weakened by the mistreatment (in prison), his bowels had ruptured, and Mairs died of peritonitis."

Mairs' decision to plead guilty in court to avoid a long sentence which he feared he would not survive, proved ironical. By a cruel twist of fate, his father, who had also been arrested at the same time, chose to plead guilty and so risk a longer jail term - and was subsequently acquitted and escaped jail. He visited his son in jail after he took ill, just a day or two before Joseph jr. died.

At Oakalla, says Leier, Mairs' death led to a coroner's recommendation to the government to have a fulltime doctor for the prisoners, rather than one who just dropped in every few days. The government implemented that shortly afterwards.

Labour slate for Cowichan schools

Keynote speaker at the Ladysmith memorial wreath-laying Jan. 18 will be Bill Routeley, president of the area's Local 1-80 of the Industrial, Wood and Allied Workers union. Also to speak are Marilyn Bridges, president of the NDDLD; Haythornthwaite's son Gabe as labour School Trustee in the area's School District 79; and Jean Crowder, a labour municipal councillor from North Cowichan.

There will be short speeches and local musician Andrew Ruzsel will perform a song he wrote about the coal strike.

Haythornthwaite said he hoped that candidate Doug Routley will be elected to the local School District board of trustees under the Community Alliance for Public Education (CAPE) banner. CAPE is a labour-led alliance organizing in the Cowichan School District and has already elected Haythornthwaite's 32-year-old son as a trustee.

He said if that happens Routley will join the ranks of those who make their own self-sacrifice for the Labour movement - he's a school janitor and will have to resign his job in order to sit on the board.

Quentin Dodd, a frequent contributor to The Tyee, is a journalist based in Campbell River. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: