On Valentine's Day, 1974, British doctors destroyed a chunk of Derek Wright Hutchinson's hypothalamus without his consent. "I was strapped down and my eyes were taped open," remembers Hutchinson, now aged 60, of the neurosurgery called a hypothalomotomy, first developed in the 1950s to curb aggressive behaviour. Surgeons drilled two holes into his forehead, then sent a wire with an electrical tip deep into his brain. Before destroying the specific target, the surgeon test-stimulated his brain with five to 10 volts of electricity. "They'd say, 'Are you frightened? Angry?' I yelled, 'Stop it, or I'll kill you." But I couldn't move. Then they thermocoagulated my hypothalamus. I felt as if I were in a coffin. I felt heat all over my body as if I were being burned alive. Oh, pal, I can't find the words. I have to find the words."

Hutchinson has gone on to become an activist rallying against the continued use of psychiatric neurosurgeries and a procedure called deep brain stimulation (DBS) done at centres round the globe, including a UBC "limbic surgery" program and a UBC/VGH clinical trial of DBS for depression. (See The New Lobotomy) These invasive procedures have made a comeback as a last resort treatment for depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and anxiety, and in rarer cases eating disorders, addiction, self-mutilation and aggressive behaviour. Some bioethicists, psychiatrists and health research watchdogs have voiced concern about the renaissance of interest in these procedures, particularly now that media reports of the Virginia Tech mass murders have once again spotlighted a link between psychiatric illness and violent behaviour. The National Coalition of People with Psychiatric Histories has said this label is unfounded and that "research shows that people with psychiatric disabilities are far more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violent crime."

'Frankenstein's monster'

With his tattooed forearms and obvious frontal lobe scars, Hutchinson calls himself the "Frankenstein's monster" of experimental psychiatry. Hutchinson has copies of his medical files, and they do read like a nightmare Victorian fairytale. To describe the moments when his brain was being zapped, doctors jotted down: "Felt funny -- felt as if he was dying," "Feels weak and sick," and "Rapid dilation of pupils, pulse up."

This initial electrical stimulation, still done with today's psychosurgeries and DBS procedures, is meant to test whether the targeted brain spot controls emotions and not pathways crucial to motor functions like walking, talking and breathing. At points, Hutchinson would feel profound fear or have vivid flashbacks, like "memories of my grandma shouting and barking at me. It was a nightmare," he says. After that, the right and left sides of the pinpointed area of his hypothalamus were burned for thirty seconds each. The wire was retracted from his brain and two nylon balls were fitted into the skull holes to act as a crude brain cork.

The nylon balls remained, sticking out of Hutchinson's skull for over two years, like shorn "devil horns" until he demanded they be removed. According to his medical files, in 1976 a surgeon replaced them with "two plastic buttons."

Nowadays, sutures or staples are used and some centres have begun using gamma knife technology, making drilling into the skull unnecessary.

Hutchinson stumbled into the mental health system the autumn prior to the surgery. He was living with his wife and three children in Leeds in a council estate, the UK equivalent to government housing. It was the kind of place he'd called home all his life, after growing up the son of a welder who made extra shillings on the side boxing at English fairgrounds. "He was a smashing gentle fella, but me mom was an evil old drunken sod, always crackin' me head and throwing me and me [two] brothers round," says Hutchinson. "Sometimes she'd lock me in the coal shed. I'd sleep in coal sacks to keep warm and go to school lookin' like a Jamaican."

Hutchinson was a rebellious kid and a scrapper at school. His mom pawned him off on various juvenile detention schools, but after scoring 149 on an IQ test, he was sent to an experimental school for smart delinquents called Kneesworth Hall.

Calling the 'cracker wagon'

By 1973, "I was a normal bloke living in a place where if you weren't tough, you went down," says Hutchinson. Like his dad, he was a boxer and welder. His family was "surviving," but he told his doctor he was extremely depressed. The doctor "called for a cracker wagon," and Hutchinson ended up at a psychiatric hospital called High Royds Hospital in West Yorkshire. He was given "all kinds of antipsychotic drugs that would knock out a donkey, then a bunch of ECT [electroconvulsive therapy] which was like a horse kick to the head." The depression got worse and the ECT caused memory blanks.

A surgeon named Dr. Arthur Wall entered Hutchinson's life, recommending an experimental brain surgery. "He said, 'If you don't have this surgery, how would you like to think you'd be responsible for hurting your children?' But I had never threatened the kiddies," says Hutchinson. "I valued them most in my life. And the reality of the situation was that there was nothing wrong with my brain. Why mess around with it?" A December, 1973 letter from Dr. Wall to Dr. John Todd, the consultant psychiatrist at High Royds, states: "I think he would be suitable for an operation on his hypothalamus particularly because, as you say, he has no gross psychiatric abnormality."

Hutchinson said "bollocks" to the surgery. His wife also said no. "So, they went to see my alcoholic mother late at night," says Hutchinson. "She signed the consent form. The sods were going to operate on me no matter what. They were looking for an aggressive lad."

Could it happen now?

By the 1970s, the kind of crude lobotomies done from the1930s to 1950s had disappeared after the introduction of antipsychotic drugs. But a handful of centres around the globe continued to perform psychosurgeries. They targeted specific brain sites using a stereotactic frame bolted to the patient's head and x-ray imaging to pinpoint the brain target, then electrodes replaced scalpels and ice pick-like instruments. Some specialists targeted the hypothalamus and amygdala to treat violent behaviour or sexual deviance. In the UK, a total of 431 psychiatric neurosurgeries were done on citizens between 1974 and 1976 according to research, including at least seven hypothalamotomies done by Dr. Wall.

But psychosurgery didn't hit the public radar until the '70s, when well-established U.S. neurosurgeons funded by The National Institute of Health and the U.S. Department of Justice proposed psychosurgery for prisoners, violent criminals and even pre-emptively on poor African Americans thought to be genetically inferior; a Mississippi-based neurosurgeon was also performing neurosurgeries on aggressive children. Commissions were set up in the U.S., which led to bans in psychiatric hospitals and prisons and World Health Organization protocols.

Since then, Germany and Russia have banned psychosurgeries altogether, but centres in Europe, North America, India and China have continued to perform anterior capsulotomies, limbic leucotomies, subcaudate tractotomies, cingulotomies, all targeting different areas of the brain thought to be involved in psychiatric disorders. Improved brain imaging technologies have made it easier to target specific areas of the brain and informed consent is mandatory now, with the exception of Scotland, which recently allowed for a loophole to treat patients "incapable of consenting." The Canadian Psychiatric Association's set of guidelines, created in 1978 and re-approved in 2003, also includes a clause that "in cases where the ability of the subject to freely give informed consent is questionable, the final decision to recommend treatment should depend upon the deliberations and recommendations of a psychosurgery board."

Slicing the brain

The rationale for these surgeries remains the same as it was way back in the 1930s when Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz proposed that severing pathways between the deep emotional parts of the brain and the frontal cortex (known as the brain's CEO) would interrupt the debilitating thoughts of psychiatric patients.

"The assumption is that these pathways carry the circuits that are causing the disability. The surgery intercepts these brain structures that support a dysfunctional mind," says Dr. Hurwitz, a UBC-based neurologist and psychiatrist. He runs a "limbic surgery" program for severely depressed Canadians who don't improve with pharmaceuticals, psychotherapies and ECT. Since the program started in 2000, with strict patient selection and informed consent protocols, nine people have received a bilateral anterior capsulotomy targeting the internal capsule of the brain, a site now also targeted with some DBS procedures. "Most of these patients have done fantastically well post-op," he says, acknowledging that patients will continue to receive "a sophisticated battery of time-consuming and expensive neuropsychological tests" for a 10-year period to track efficacy rates.

"Depression is a terrible psychic pain, like a toothache of the soul. Our patients say this operation has saved their lives," says Hurwitz. "One patient used to hurt herself. She said, 'Now I don't have to do that anymore.' Only two patients have had problems. One elderly guy has developed Parkinson's. Another female patient has major fatigue. But her family says she's a better mother, she's raising her kids. We have seen no obvious signs of frontal lobe damage. One person showed declines in neuropsychological testing. But I think our results are better than the published results anywhere else."

Published results have varied widely over the decades with earlier reports stating efficacy rates of as much as 70 per cent. More recent studies indicate that one-third of patients will improve after one or two surgeries, with no adverse effects. But other studies have documented cognitive impairments, lowered IQ and memory problems and behavioural and social deficits. Swedish studies have found "frontal lobe dysfunction," including four of eleven capsulotomy patients. Fifty per cent of patients in another study had cognitive deficits and a quarter of patients had "significant adverse events," which can include seizures, fatigue, weight gain, memory problems, addiction, poor impulse control (such as overspending, gambling and hording), disinhibition (talking or acting inappropriately), suicide and even criminal behaviour including theft, pedophilia and sexual assault. Ironically, sometimes post-op behaviour changes magnify a patients' original mood disorder.

Violent secrets

"I felt as if I could have killed someone," says Hutchinson about his wild mood swings and paranoia. Fearing that the doctors would order another surgery or additional ECT, he "didn't dare tell anybody" about his increasingly obsessive violent thoughts, particularly since they were primarily targeted against his doctors. He was released from hospital a week after the surgery.

"That Sunday, I took the kiddies for a walk in the park," he recalls. "Two blokes attacked me and broke my arm. So, later I went after 'em." In the past, Hutchinson might have settled the score with a punching match. Now, he was grabbing a machete, "fully intending to kill 'em." He was ramming the front door when the police showed up and charged him with aggravated burglary. But his doctors helped convince the court to give him a suspended sentence. Hutchinson started binge drinking and experiencing blackouts. After his wife gave birth to twins, he threatened her with a gun. "That wasn't me. I just wasn't myself anymore. I walked out on my family because I knew I was now capable of hurting them," he says.

His memories of the next two decades are spotty, like trying to piece together a vague nightmare. Hutchinson's medical records describe repeated overdoses and hospital stays for additional ECT while he was working as a safety inspector "in aerospace." One entry states that he "complains that since the [surgery] he is like a 'lion without any teeth.'" At some point he also attacked one of his psychiatrists, but no charges were lodged against him.

New beginnings

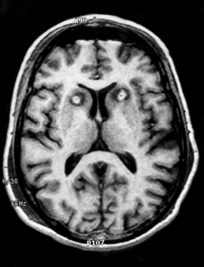

Hutchinson met his current wife, Carol, in a pub, and they married in 1982. "She's had a hell of a time with me," he says of the bouts of depression, impotence, insomnia, extreme fatigue and rage he's experienced since the surgery. He's had eight heart attacks, two strokes, has battled anorexia (the hypothalamus also regulates hunger, blood pressure and hormones) and has tried to kill himself seven times. "Sometimes I forget how to play games with the grandkiddies. Nobody knows why I've survived," he says. "I get a lot of headaches, like an ice pick and hot melting pain." He also has daily flashbacks of the operation and has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. A 1996 MRI of his brain revealed extensive damage. "They said, 'Half of your hypothalamus is gone.' That's when I finally woke up."

Hutchinson, by then grandfather to "a rugby team of kids" (now 17 in total including Carol's grandkids), started campaigning against psychosurgery, ECT and psychiatric drugs by organizing protests, writing newsletters and starting his own one-man operation called "SCALPS: Survivors Campaign Against Lobotomy and Psychosurgery." He's participated in various mental health executive committees and regularly visits psychiatric wards, educating patients on the risks of pharmaceuticals and ECT. "People with mental illnesses are treated like lepers in our society," he says. "There's nothing worse than it -- never a light at the end of the tunnel. It's easy to just go crazy. But I've never been a victim. I can't have this dark cloud of abuse hanging over my grandkids. I won't accept nothing can be done. If I do, the Frankensteins win."

The most striking thing about Hutchinson is that his sense of humour and his smarts have somehow remained intact. I've met two Canadians who have had psychosurgeries to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) as recently as 2003, and neither expressed such a compelling grasp of the abstract neuroethical issues. For example, Hutchinson -- who is adept at using the computer and Internet, despite a typing speed he jokes is "10 words per day" -- e-mailed me with his own list of questions for psychosurgery proponents, such as "Where in the Brain is the 'MIND' located?" And, "How would someone decide which part of the MIND does the illness come from and then how would he localize and then Destroy an 'EMOTION' Such as love, anger, sorrow, grief, etc, etc, etc."

Neurosurgeons I've spoken with admit that they can't see physical abnormalities in a mentally ill patient's brain and that the long-term effects are unpredictable. How or why such invasive procedures might work to curb psychiatric disorders like depression and OCD still remains a mystery. Brain imaging technologies can now show neurological blood flow changes that might reveal specific targets for emotions from sadness to aggression (so-called "brain fingerprints" are already used in criminal courts, or even to indicate predisposition to potential future violence), but we're also learning that the brain is an incredibly complex web of over 100 billion neurons that interconnect intellect, emotions and motor functions.

Inexperienced 'hotshot' neurosurgeons

Ethicists worry that even with strict ethical guidelines, the popularity of psychosurgeries might increase again given the increased number of people diagnosed with mental disorders and new brain imaging techniques. One group in Italy has recently used DBS to treat aggressive mentally handicapped patients.

Dr. Katherine Darton of Mind is concerned the current zeal for tinkering with the brain "may lead inexorably towards increasingly invasive procedures" that carry "serious risks.... Mind is not happy with the continued use of psychosurgery and believes that there should be a rigorous review to determine whether any continued use is justified."

Even proponents are concerned that these surgeries are already being done by inexperienced neurosurgeons without strict patient selection protocols, informed consent and long-term follow-up studies.

"It's worrying that a hotshot surgeon can just go into a person's brain and try something before research has proven efficacy," says Hank Greely, a Stanford-based bioethicist who's concerned that since surgeries don't have to be regulated like drugs or medical devices, there's a greater potential for misuse. "Even then, the questions become, 'Should we use it?' and, 'What is the acceptable price?' Mind control is a loaded term, but these issues are much more complicated with behaviour disorders. There's an allure with the new neuroscientific tools and we should have better accounting and control."

'Anatomy of anger'

Dr. Hurwitz, who trained in Boston in the '70s when these surgeries were still being done to treat aggression, says that it would be "unacceptable" to see a new wave of neurosurgeries to treat violent behaviour, even though he thinks neuroscience has revealed "the anatomy of anger. But, today no thinking person should support this kind of surgery," he says, though he acknowledges that with behaviour control techniques "there can be a slippery slope and the pendulum can swing the other way." For example, the recent Virginia Tech murders. "People will be asking: 'Why didn't psychiatry intervene?' Events like that spotlight the fine balance between an individual's autonomy and society's obligations. We won't always get that balance right. It will always be a grey area."

Hutchinson thinks psychosurgery should be banned outright because he believes that mental disorders are caused by an individual's unique life experiences, not a product of a dysfunctional brain.

He has been nominated for this year's Mind Champion award in England precisely because he is an effective mental health advocate in describing what it's like to go through a psychosurgery and what the problems with such procedures are.

Hutchinson is a keen supporter of psychotherapies, like the "talkin' therapies" he's been doing for six years, which he credits for saving his life. "We must put an end to this immoral, unethical activity being conducted in the name of mental health research," he says. "These doctors are guinea-pigging innocent people. These surgeries should never have been invented. They kill the person and they don't even know they're not the same person anymore."

Related Tyee stories:

- The New Lobotomy?

'Deep brain stimulation' tested at UBC as depression cure. - How Horror Sparks Our Brains

'Mirror neurons' drive the biology of empathy. - Psychedelics Could Treat Addiction Says Vancouver Official

City's drug policy honcho sees 'profound benefits'. A special report.

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: