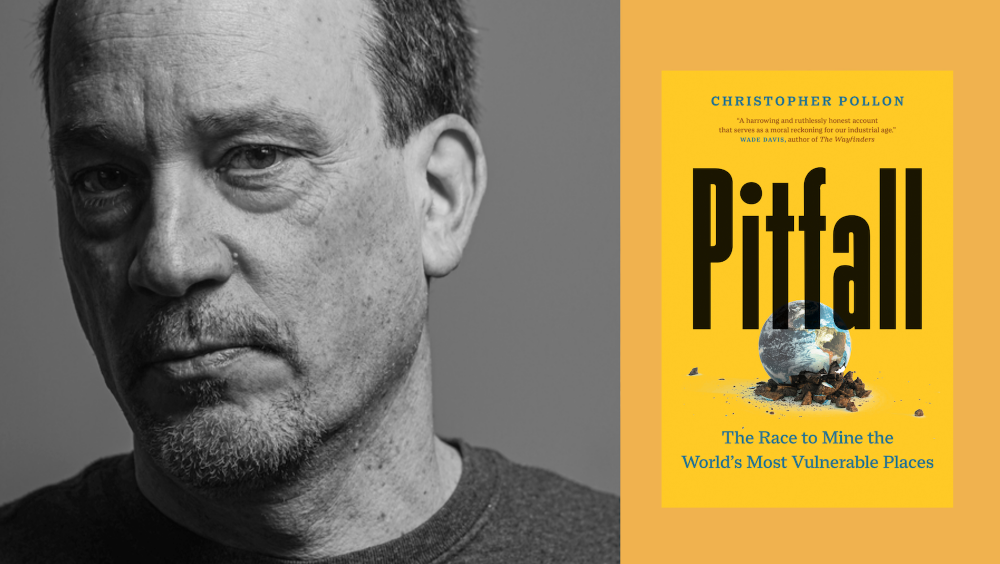

[Editor’s note: This is drawn from 'Pitfall: The Race to Mine the World’s Most Vulnerable Places,' published by Greystone Books in partnership with David Suzuki Institute. It’s an essential exploration of the accelerating mining boom and ways to tame its worst effects on humans and the planet. Read a Tyee interview with author Christopher Pollon and attend a free, live event with the author at 7 p.m., Oct. 12, at Vancouver Central Library.]

In a relatively short time, Canada has morphed from backwater resource colony to global mining colonizer. We are the inventors of the modern junior mining company — a small, nimble corporate vehicle designed to raise high-risk capital. At its best, Canadians scour every corner of the Earth, drilling exploratory holes in the ground on a quest for minerals the world needs; at its worst, zombie companies loot investors and feed popular cynicism about the mining business.

There is something incongruous, at first glance, about the emergence of Canada — a nation of about 40 million known more for being over-apologetic than for a cutthroat approach to resource capitalism — as a global mining power.

For more than 60 years, Canadian-flagged mining companies have found success hiding behind the image of the peacekeeper and honest broker to become the vanguard of a global mining exploration industry. Today Canadian companies dominate mining in Latin America, while controlling immense mineral resources across Africa, North America and Asia, with mining assets in about 100 countries globally.

Canada is also one of three global centres for raising mining capital, in addition to Australia and England. And Canadians have claimed a near monopoly over precious metals in Latin America that continues to this day. By 2007, Canadian mining corporations were leading over 1,500 projects across Latin America, almost all of them for gold and silver.

Several factors made this dominance possible. In 1971, the U.S. ended the gold standard, which previously held the price of an ounce of gold at a constant $35; once this control was lifted, it blew up to $600 per ounce by the end of the decade, making gold mining immensely profitable. Scarcity after two centuries of mining the best Canadian and American gold deposits also sent miners looking further afield. Latin America was where the best action was, and where historical gold and silver districts were already well known — “the real El Dorado,” according to McGill University historian Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert. The result was that “Canadian-based corporations colonized the Latin American precious mining sector.”

This ascendancy could not have occurred without the loosely regulated stock exchanges, based in Toronto and Vancouver, that provide financing for junior-level companies. Toronto rose as a financial mining centre in the early 20th century because it embraced the high-risk mining investment and promotion that Wall Street would not.

Meanwhile, on the notorious wild west Vancouver Stock Exchange, the amount of mining capital traded jumped 10-fold from 1978 to 1987, as Vancouver carved out a niche as the “heap-leaching capital of the world,” in the words of Studnicki-Gizbert.

The billionaire mining mogul Robert Friedland, who made his first fortune uncovering a massive nickel deposit in Newfoundland, attributes Canada’s lasting influence on mining in part to the junior mining exploration company — a small, nimble corporate vehicle designed to prospect for resources, find good deposits and sell them to bigger companies with the wherewithal to develop a mine.

The other factor, Friedland says, was the creation of a venture capital market system capable of financing these little companies, enabling them to go forth into the world. “Canadians invented the junior mining company and led the world with that, the Canadian spirit of being able to conquer anything,” he told a Vancouver mining exploration conference in early 2021. “Canadians have gone virtually everywhere on this planet and made it work.”

Today almost half of the world’s publicly traded mining and exploration corporations fly the flag of Canada. As you read this, there are Canadian companies prospecting for metals in every corner of the planet, including on the deep seabed, and as soon as they are provided with an economical way of doing it, they will scout the surface of asteroids and sub-planetary metallic boulders barrelling around the solar system. The Finns build ships, the Swiss are bankers, and Canadians travel to all corners of the Earth, promoting exploration companies and drilling speculative holes in the ground.

The Canadian government and mining industry like to promote Canada as a mining leader in the world — pointing to the TMX Group, which hosts both the Toronto Stock Exchange (for bigger companies) and the TSX Venture Exchange (for small, early-stage companies, dominated by junior miners). Mining companies on these exchanges have raised $44 billion between 2018 and 2023 alone — over half of the world’s public mining financings, and almost 40 per cent of all the money paid by investors to buy mining stocks globally.

On Mining.com’s 2023 list of the 50 biggest mining companies, seven are Canadian — including Barrick Gold, First Quantum, Teck and Ivanhoe — mostly specializing in copper and precious metals. Barrick Gold is among the biggest: a company that is Canadian in name, but whose corporate structure reveals a truly global enterprise. Beneath its Toronto head office are over 120 “significant subsidiaries, operating mines and projects,” including companies registered in the Cayman Islands, Barbados, Delaware and the tiny British Crown Dependency island of Jersey.

A vast majority of Canadian-based mining companies — 1,048 of 1,208 in 2015 — were smaller junior mining companies, with a stock value of less than $10 million. To put Canada’s role as a mining leader into perspective, by 2014 the cumulative capital value of all shares for about 1,500 mining companies listed on the Toronto exchanges was less than the combined capital value of the world’s two biggest mining companies at the time — BHP and Rio Tinto (neither of which are Canadian).

According to French Canadian author and professor of political philosophy Alain Deneault, Canada has become a “regulatory haven” for small, exploration-stage mining companies.

“The romance of Canada’s universal goodness, partly arising from Canadian peace-keeping operations, begins to unravel as soon as we are confronted with the sorry environmental, social, political, safety and tax record of the extractive industry hosted by Canada,” writes Deneault in Canada: A New Tax Haven; How the Country That Shaped Caribbean Tax Havens Is Becoming One Itself.

“Throughout the world, parliamentary commissions, courts, UN experts, independent observers, specialists in the economy of the South, and experienced journalists have testified to the injustices — and sometimes crimes — committed or massively supported by Canadian mining companies active in countries in the South,” writes Deneault.

There are currently at least 800 junior mining companies headquartered in and around my home city of Vancouver, which, despite its many charms, is not to be mistaken for a global centre of finance. If the odds of an explorer finding a mine are somewhere between one in 500 and one in 1,000, what day-to-day money-making business are these companies in, exactly? No one really knows for sure, and regulators have been slow to find out.

An uncertain number of these companies are “zombies,” says Tony Simon, co-founder of the Venture Capital Markets Association and an activist mining investor. Simon has brought national attention to the “zombie mining companies” of Canada, which are, simply put, companies with no real interest in either mining or paying their bills.

In 2015, Simon identified at least 600 zombie mining companies with “negative working capital” listed on the Toronto stock exchanges, representing exploration assets worth billions of dollars. (By December 2019, that number had dipped to about 400.) He tells me they are kept alive, in spite of negative cash flow, by the for-profit TMX Group that owns the exchanges, which would lose significant fees if the companies were delisted.

Simon adds that the TMX Group has rejected his call for a cull of companies not seriously engaged in mineral exploration. (Reached in spring of 2023, a representative of the Toronto-based TMX Group declined to comment on Simon’s allegations.) Such a purge would go far in eliminating zombies, of which a certain number are what Simon calls “lifestyle companies,” a largely Vancouver phenomenon he describes to me as if setting up a long-winded joke:

“So these guys have formed a company, you get a guy who will sit in a bar and he tells you, ‘I have a [publicly] listed company, ABC, and we’re a wonderful group, we’ve got a property in Africa that’s going to be the next great thing.’ You figure, ‘What the hell?’ and put in five grand. He does that to enough people that he raises $300,000. And he takes the $300,000, pays the listing fees, the rest of it, he maybe makes an announcement: ‘We’re going to do a geophysical study of our African property.’

“So maybe you’re keeping track, you see they’re doing it. Maybe they do part of it, and don’t pay [the workers]. And in the meantime, he’s operating the company out of his apartment in downtown Vancouver, and the company pays the rent, he goes [to the bar] every night, fuckin’ drinks his face off, eats there, and charges it to the company.

“And so, at the end of the year, he has spent $300,000, and what has happened? Nothing. But if you look at his life, pretty damn good. He’s been able to pay his rent and food, chase after chicks, and life is good. And that’s what they do.”

All this might sound harmless, except to the bamboozled investors, but zombie and associated lifestyle companies suck up capital that could be going toward finding new minerals. And it illustrates the reality that the current mining model, built on casino-style speculation of junior mining companies, does not possess the capacity on its own to find and reliably supply the metals we need for the clean energy transition, without inflicting undue harm, including on investors.

I ask Simon how many exploration companies are needed, in his ballpark estimation, to explore all the worthy properties on the face of the Earth. “The answer is, I don’t know, 500? Seven hundred?” he replies.

“But it sure as hell wouldn’t be 14 or 15 hundred. You don’t need ’em!”

Author Christopher Pollon discusses his new book 'Pitfall' at a free event on Oct. 12 at the Vancouver Central Library. ![]()

Read more: Books, Local Economy, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: