It’s great to eat home-cooked meals for a variety of different reasons. They tend to cost less money and be more nutritious. They offer a way to incorporate in-season and local foods — strengthening food systems at a time when supply chains are increasingly fragile.

But when media covers local food and home cooking, lots gets left out.

As my colleague Christopher Cheung wrote in a series earlier this year, local food is more than kale and scapes — it’s fish cakes and kimchi and phyllo, too.

Snobby approaches to what exactly constitutes cooking in this paradigm also besmirch canned and frozen vegetables, prepared aromatics and the use of tools such as food processors and electric pressure cookers — even when these foods and tools help facilitate home cooking for disabled people.

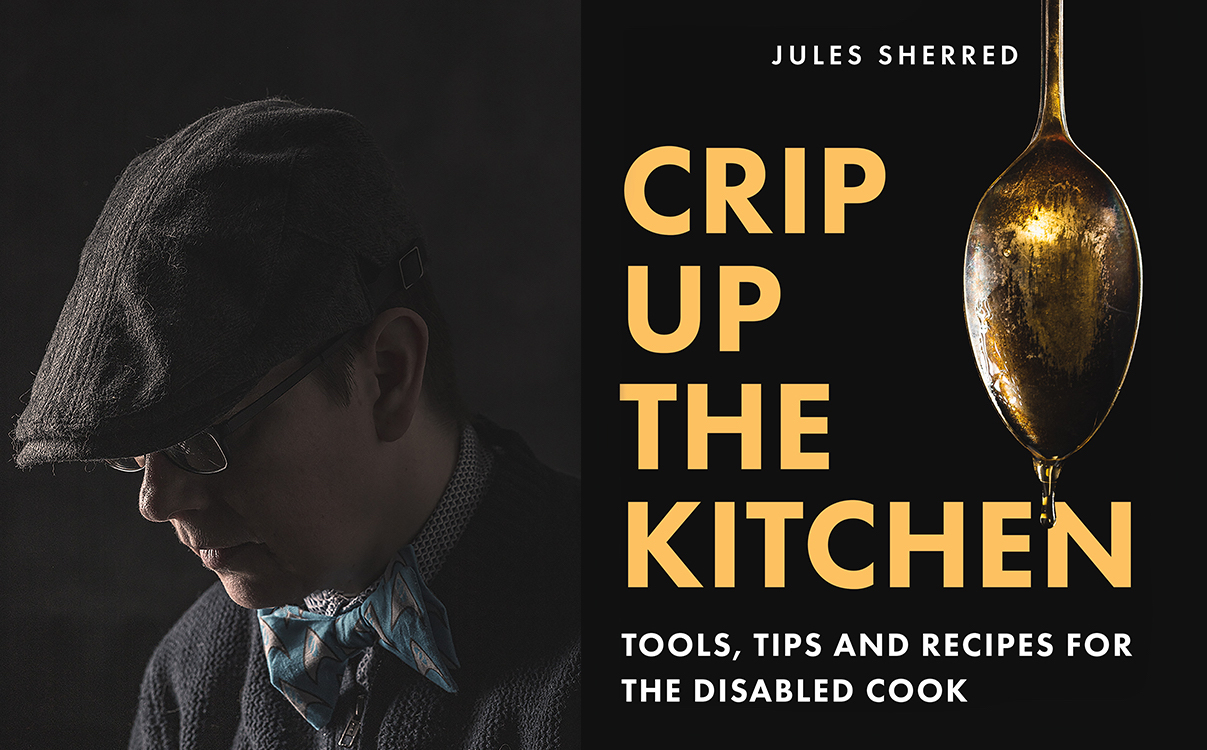

Enter writer and food photographer Jules Sherred’s new book, Crip Up the Kitchen, which aims to make home cooking more accessible and culturally relevant for disabled and neurodivergent cooks and would-be cooks. The book organizes recipes by the level of effort required to make them, recommends tools that help prevent pain and reserve energy and offers a step-by-step guide to pressure canning — one way to take longer-term advantage of batch cooking on days when you’re feeling more up to it.

We caught up with Sherred to ask him about ableism and the kitchen, and how Crip Up the Kitchen opens new possibilities for disabled cooks. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: I think sometimes when cooking is discussed by media, we talk about a Platonic ideal that isn’t broadly achievable or even desirable for many people, for many reasons, including disability. And it’s rolled into moral judgments about health, and “ethical consumption,” and just a whole hornet’s nest of things. Which is what I was thinking about when I was paging through your new book. I thought it could be a good place to start to ask you what drew you to writing it? And what role are you hoping it fulfils in the world of cookbooks?

Jules Sherred: Aside from just the general anger and frustration of able-bodied people pooh-poohing the tools that disabled people need to be able to feed themselves, I was also really fed up with the general idea that we are lazy if we use pre-chopped anything, if we are buying minced garlic, if we are using frozen vegetables. It was all of this crap — ableism paired with diet culture — and I had just had enough.

I’m hoping that just having that message repeated over and over again — that you’re good enough exactly as you are, and whatever you do to be able to feed yourself, congratulations, you’re succeeding and you’re a real cook. This whole idea that you’re only a real cook if you’re doing every single piece from scratch? No. You threw stuff into an Instant Pot and you cooked. Congratulations, you’re a real cook. Bottom line, period, full stop.

What are some of the more common barriers that disabled folks face while cooking? Could you share a couple of examples of how you navigated those barriers while writing this book?

The biggest ones that are most common, regardless of disability, are fatigue, pain and cognitive impairment. Those three are shared amongst a wide group of people.

I have a method in the book that people can tweak for their own needs that is based off Spoon Theory, where you create a chart of tasks that you know that you’re able to do, based off a self-assessment of how much energy you have. What I do personally is I assess my spoon levels in the morning, I pick a task based off that, and then I reassess again after my lunch break. If I still have more gas in the tank, then I add, or if I’m down to one, then I’m done for the day, because I want to have something in reserve for night. And then I reassess at the end of my workday. The goal is to always have at least one spoon left, so that I can do other things, instead of dying at 6 o’clock because I have nothing left.

And then to feed myself: all of my recipes, well, most of them, are batch cooking. Instead of one meal, it’s enough for three or four meals, and then you either pressure jar or you freeze it. I always have two weeks to a month of prepared food in my cupboards. Sometimes it gets dwindled, because life happens, and I get months where I’m more worn out. But as soon as I have the ability to restock everything, I fit in time throughout my week to do another 16 servings of butter chicken and then I’ll jar that, and it’s ready to go.

Even if you don’t have something in reserve — I have a soup recipe that takes five minutes. It’s just opening cans and throwing it into the Instant Pot and blending it and you have some soup. There are tips for easy ways to add protein to it. And you’re fed. It’s all about making sure you’re not pushing beyond what you’re capable of in that exact moment.

That segues really nicely into another question I wanted to ask. So you own six — an impressive six! — electric pressure cookers. Could you talk a bit about what makes things like pressure cookers and electric can openers so useful? And why other disabled folks might want to start keeping an eye out for them on their local buy and sell pages?

The pressure cooker is the big one. And same with bread machines, because you basically dump a bunch of ingredients into it, you set the time and you walk away, and you’re done. You don’t have to think about it, you don’t have to babysit it on a stove. You’ve already expended all this energy, and accumulated pain preparing it. Every single minute counts. An electric can opener, again, there’s no having to worry about having the ability to turn a crank on a can opener.

All those things contribute to expending energy and adding pain. It’s circular: pain feeds fatigue and fatigue feeds pain. Anything you can do to cut that circuit is absolutely necessary. All the tools that I recommend cut that circuit in some way, so that you’re not spending more energy or introducing more pain into the process wherever possible.

I was reducing a strawberry purée on the stove recently, and it was going to take half an hour, and I realized I could pull a chair over to the stove and sit there with a wooden spoon instead of standing. I worked in kitchens for 10 years. I don’t know why it hadn’t occurred to me before.

That reminds me — with a pressure cooker, you don’t have to do it in your kitchen. You can be sitting in your living room, put the pressure cooker on your coffee table and be relaxing, watching something on TV while you are feeding yourself. How awesome is that?

Another thing: prepping at your dining room table or kitchen table, sit down and do it. That’s what our grandparents did. For some reason, we lost that amazing piece of wisdom, which was how kitchens functioned for hundreds of years. And then we decided that aesthetics were more important than function and we stopped using our tables as work tables.

Thinking again about those common criticisms that we often see from chef activists about the North American diet — we eat too much processed food, grocery shop more frequently, prepare and cook things fresh daily. And that all we need to get started doing that is a good knife and a chopping board and a pot and a pan, it’s really simple.

It felt very freeing to see you offer a completely different approach to facilitating the eating of home-cooked meals on a regular basis, which is the batch prepare method and the batch cook method, and using these different tools that we have available to us. And even just freezing things, so we can toss them in. Why do we not see this offered more regularly as a solution? Do you think we need to see a cultural shift in terms of the way media discusses food and cooking?

We need to see a cultural shift. But we also need to remove ableism from it, because it’s also rooted in ableism and diet culture. Somewhere along the line we were told preserving food is wrong. We used to have root cellars. We used to have pantries full of canned goods. We used to freeze stuff once we had the ability to do so. I have to guess it’s somewhat rooted in ableism and maybe a backlash against the fad when microwaves and and instant dinners and stuff came in. And then trying to go back to traditional roots. Not understanding those traditional roots were based in batch cooking and and conserving our foods. We didn’t always have the time to sit down and cook every single night. It was a luxury. And it’s also ableism because you’re lazy if, heaven forbid, you buy an orange that’s peeled in the store. So people who cannot use their hands are able to eat an orange.

So there’s this myth of not understanding the history of food and food systems, combined with ableism. And the fact that the worst thing you can be is disabled. I see it all the time in conversations — “I would rather be dead then have X type of disability,” especially from parents of autistic kids. Your kids hear that, right? Your kids can see that you feel like your child is dead because they’re autistic. No. I’m autistic, and I’m fabulous. Thank you very much. There’s nothing wrong with me. Society is the issue.

That’s why the book is called Crip Up the Kitchen. We need to intentionally make space for disabled voices and people in the kitchen. It’s a call to action to undo ableism in cooking methods.

The other thing that crops up in your book is the mental space that it takes up to meal plan and grocery shop and stock a pantry all while trying to avoid food waste. I think a lot of people find this tricky. And then if someone has disabilities, such as ADHD, there’s an added layer of difficulty. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about how you navigate that in Crip Up the Kitchen.

I have an equipment list for each recipe, so that people know exactly what they need, and they don’t have to guess and figure out that they’re missing something halfway through cooking, walk away to try and find it and then forget what they’re doing. I have a reminder to prepare a mise en place, because that is another thing that saves time. And I have ingredients that are used more than once broken up in the ingredient list. A lot of the time that stuff gets broken up in the method, and people with neurodivergencies see it as a surprise. I have both the metric and the imperial listed so there’s no having to flip through conversion charts. Substitution tips, anything that would affect grocery shopping, is at the top of the recipe.

Anything that is a common block for someone, that leads to them feeling overwhelmed, I’ve built that into the way the recipe is written.

Meal planning is at a month in advance of instead of a week. So it’s like pick eight recipes, figure out what the common ingredients are, spend some time every two weeks chopping — not every single day — and freeze those ingredients. Make sure your pantry is well stocked. And that way, if you find yourself with the energy to cook, it’s just a matter of pulling ingredients from the freezer, non-perishables from the pantry, throwing it into your Instant Pot, and you’re done. It’s that simple. There’s no thought. There’s no planning. There’s definitely a little bit of work needed at the beginning, but once you’ve done that, you’re set. It’s just it’s a much easier system to maintain and navigate.

Do you have a favourite recipe in the book you could share with us?

That would be the Doukhobor borscht. It’s the most spoons, but it’s the one that was the most important for me personally, for my own reclaiming and reconnecting with my culture. It took me six months to develop and the day that I finally cracked it, I cried. All of them have cultural significance for lots of different reasons. But the Doukhobor borscht has the most meaning to me.

Electric Pressure Cooker Doukhobor Borscht

This classic dish is worth every “spoon” it takes to make it. As a bonus, serve it with cubes of aged cheddar cheese or sour cream and a sprig of fresh dill.

PREP: 45 minutes

COOK: 30 minutes

NATURAL RELEASE: 10 minutes

TOTAL: 1 hour, 25 minutes

CUISINE: Doukhobor

HEAT INDEX: None

STORAGE: Freeze, or jar at 11 lb (76 kPa) of pressure for 60 minutes

SERVINGS: 12 x 1 cup (250 mL)

CALORIES PER SERVING: 299 kcal

Gather equipment:

- 2.84 L electric pressure cooker or saucepan

- 5.68 L electric pressure cooker

- Cutting board

- Knife

- Carrot peeler

- Food processor

- Food grater with fine holes

- Measuring cups and spoons

- Can opener

- Stainless steel mixing bowls

- Potato masher

- Tongs

- Slotted ladle

Prepare and Mise en Place Ingredients:

- ½ cup plus two tablespoons (150 mL) unsalted butter, divided into ¼ cup (60 mL), one tablespoon (15 mL), ¼ cup (60 mL) and one tablespoon (15 mL)

- One cup (250 mL) chopped yellow onions, divided into ¾ cup (185 mL) and ¼ cup (60 mL)

- ¾ cup (180 mL) chopped green peppers, divided into three × ¼ cup (60 mL)

- ½ cup (125 mL) finely grated carrots

- 796 mL (28 oz) can crushed tomatoes

- Five cups (1.25 L) shredded cabbage, divided into two cups (500 mL) and three cups (750 mL)

- Six cups (1.5 L) water

- One tablespoon (15 mL) salt

- Four medium russet potatoes, peeled and cut in half

- One small beet, peeled

- ½ cup (125 mL) chopped carrots

- ¼ cup (60 mL) chopped celery

- One cup (236 mL) whipping cream, divided in two

- ¾ cup (185 mL) chopped green onions, divided into ¼ cup (60 mL) and ½ cup (125 mL)

- Two tablespoons (30 mL) fresh chopped dill (or 1 tablespoon dried dill), divided in two

- One cup (250 mL) diced potatoes

- Black pepper (to taste)

Substitution: To make this dish vegetarian, replace the ground beef with the equivalent amount of your favourite ground plant-based product, like Impossible ground “beef,” substitute no-salt-added vegetable broth for the beef broth and omit the Worcestershire sauce. The time under pressure remains the same.

Variation: If you’d rather make hamburger soup, drain the beef after step one to remove some of the fat and do not add the cornstarch-and-water mixture at the end.

INSTRUCTIONS

- Turn the 2.84 L electric pressure cooker on to sauté. If using a saucepan, heat to medium.

- Once it’s hot, add ¼ cup (60 mL) of the butter, ¾ cup (185 mL) of the chopped onions, ¼ cup (60 mL) of the chopped green peppers, and the finely grated carrots. Sauté until the onions are transparent. Do not brown.

- In the same electric pressure cooker or saucepan, add the crushed tomatoes, 1 tablespoon of the butter, and the remaining ¼ cup (60 mL) of chopped onions. Simmer until thick, about 5 minutes. Press cancel.

- Pour the contents into a storage container and set aside. Put the inner pot back into the pressure cooker.

- Turn the three-quart (2.84 L) pressure cooker on to sauté, or the saucepan to medium. When it’s hot, add two cups (500 mL) of the shredded cabbage with ¼ cup (60 mL) of the butter. Sauté until tender. Do not brown. Press cancel when done.

- In the 5.68 L electric pressure cooker, add the water, salt, halved potatoes, beet, chopped carrots, chopped celery and ½ the sauce from step four.

- Place and seal the lid. Set to high pressure for 10 minutes.

- Quick-release the pressure.

- Remove the lid. Remove the potatoes and mash with the remaining 1 tablespoon (15 mL) of butter, ½ cup (120 mL) of the whipping cream, ¼ cup (60 mL) of the chopped green peppers, ¼ cup (60 mL) of the chopped green onions, and one tablespoon (15 mL) of the fresh dill (or ½ tablespoon/7.5 mL dried dill). Set aside.

- In the six-quart (5.68 L) electric pressure cooker, add the diced potatoes and the remaining three cups (750 mL) of shredded cabbage.

- Place and seal the lid. Set to high pressure for five minutes.

- Quick-release the pressure.

- Remove the lid. Add the mashed potatoes from step nine into the electric pressure cooker.

- Place and seal the lid. Set to high pressure for five minutes.

- Natural-release pressure for 10 minutes, then quick-release any remaining pressure.

- Remove the lid. Add the remaining ½ cup (120 mL) of whipping cream, the remainder of the sauce from step four, the sautéed cabbage from step five, the remaining ½ cup (125 mL) of chopped green onions, the remaining ¼ cup (60 mL) of chopped green peppers and the remaining one tablespoon (15 mL) of fresh dill (or ½ tablespoon/7.5 mL dried dill).

- Discard the whole beet. Season to taste with black pepper.

- Let it sit for a few minutes with the electric pressure cooker lid on before serving to allow the flavours to mix. Serve hot.

Recipe by Jules Sherred from Crip Up the Kitchen: Tools, Tips and Recipes for the Disabled Cook, copyright © 2023 by Jules Sherred. Reprinted with permission of TouchWood Editions. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: