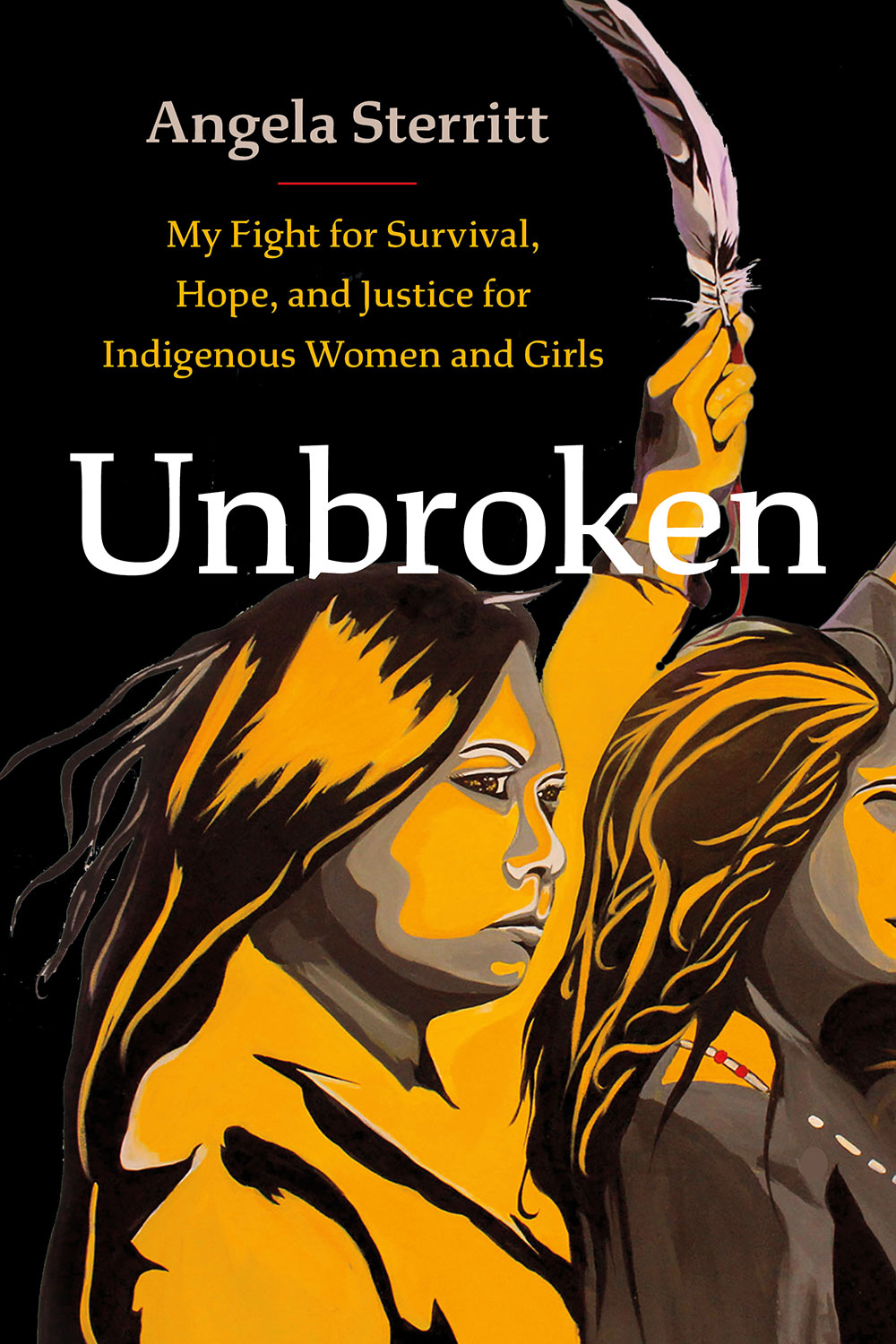

[Editor’s note: ‘Unbroken: My Fight for Survival, Hope and Justice for Indigenous Women and Girls,’ out now from Greystone Books, chronicles Gitxsan journalist Angela Sterritt’s journey of trauma and healing while fighting for recognition and justice for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls and Two-Spirit people, and more broadly, their protection and justice.

It is a personal search, as well as a journalistic one — “searching for answers about my identity and vulnerability took me on a journey where I learned about Indigenous women whose lives often mirrored or shared themes in mine,” Sterritt writes in the preface to the book. In this excerpt, Sterritt shares the history of what is now known as Vancouver, in particular what is now known as Gastown and the Downtown Eastside, up until the point she moves to the neighbourhood as a teenager in the 1990s.]

The land here opens up like a palm from a fist. Coniferous mountains push up from the shore as waves crinkle across the Pacific. Colossal red cedars and western hemlocks hug the slopes of the Ch’ich’iyúy Elxwíkn (“twin sisters”) and other towering mountains. Cedar scents blow through legions of trails that circle the rainforests as lush moss drips from bigleaf maples — the namesake of what now sits smack at the centre of this striking sight. K’emk’emeláy means “place of the maple trees,” or more specifically, of many maple woods or groves of maple woods.

“This was one of the names for Vancouver, where we would harvest trees higher than some skyscrapers,” says Marissa Nahanee, a Skwxwú7mesh cultural leader, who is also a close family friend. The maple wood was used for homes, paddles and tools like bows and arrows, she tells me. Some Skwxwú7mesh people have shared that this is just one name for the coastal city, with most titles describing smaller villages or areas used for gathering wood or plants, fishing or hunting animals for food and clothing. Lek’lek’í was one of the names to describe what is now called Crab Park, near Gastown, the neighbourhood that shaped the beginnings of what is now known as the city of Vancouver.

Where now stands an iconic steam clock and upscale art galleries and furniture shops once grew swaths of devil’s club, huckleberries and salal bushes in an understorey of the rainforest. Frogs hopped in the swamps, while grouse waddled from the woods. Indigenous people thrived on the wealth of the waters too, including the oysters and mussels on the pebbly shores that wrap the land. Before it became one of the most expensive cities in the world, this area was a gathering place used by the Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) and xwməθkwəy’əm (Musqueam) for thousands of years.

The once generous, resource-rich rainforest was cut up and slashed through by the new colonials who came to the coast in the 1800s. Settlers turned the shoreline into a seaport that gave way to logging booms, the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Hastings Mill sawmill, and later to roads leading to businesses like the Globe Saloon, owned then by John “Gassy Jack” Deighton. Until 2022, his statue stood prominently in Maple Tree Square at the junction of Carrall, Powell and Water Streets, the former site of his saloon in the neighbourhood named after him, Gastown.

Deighton, called Gassy Jack for his talkativeness, had two S̄kw̄xwú7mesh wives during his life, one just a girl named Quahail-ya or Wha-halia, 12 years old. According to Skwxwú7mesh oral history, the girl eventually ran away from her much older husband when she was 15. T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss, a S̄kw̄xwú7mesh woman who wrote a poem about Quahail-ya, says her bravery makes her a role model for Indigenous women. Gassy Jack’s statue was defaced by red paint on at least one occasion and was toppled by a crowd of protesters during the Women’s Memorial March in February 2022. Indigenous women have said his former wife Quahail-ya, now long deceased, should have a statue to replace his.

In the early 1900s Gastown stretched from today’s downtown nearly to Main and Hastings. The Downtown Eastside was once the most important retail, political and cultural centre of the city, encompassing Chinatown, Gastown and Strathcona. In the 1950s, though, shops and theatres moved toward Robson and Granville Streets, and as tourist traffic deteriorated, the hotels became rundown. By 1965 the Downtown Eastside started to face a steep decline, shaped by hard drugs and an influx of mentally ill patients released from institutions without being given resources like supportive housing. Its deterioration was amplified by the federal government’s deficit-cutting agenda that put a halt to social housing in the ’90s.

And that’s when I stepped onto the scene.

As a bright, creative and sassy teenager, I didn’t plan to live on the outskirts of the Downtown Eastside. I was ambitious. As a girl, I had dreamed of becoming an artist, a model or a business owner. Looking back at my school records and reliving the instability and trauma, I don’t recall having space to imagine living out any dream I had. I rarely was anywhere for longer than two years. I was sometimes in survival mode as a child. But as a teenager, surviving the circumstances I’d been placed in gave me a better understanding of the world that was sharply divided by privilege and power on one side and disfranchisement and exclusion on the other. My experiences gave me aspirations of achieving something beyond my own success: I wanted to change that world.

Nonetheless, there I was, a teenager living in downtown Vancouver and the Downtown Eastside in an SRO — a term I see now as just a euphemism for “shifty hotel.” SROs line poorer areas in North American cities like Toronto, New York and Vancouver. They are typically rundown residential hotels characterized by small rooms with just enough space for a bed, a chair, and if you are lucky, a sink and a dresser. In the beginning these units in the Downtown Eastside housed itinerant labourers, but with the changes in the neighbourhood, like the Hastings Mill closing down, the buildings shifted to mostly housing low-income people who spent most of their welfare cheques on the rent.

The SROs I lived in were infested with bedbugs, dealers and perverts. They were usually in various stages of disrepair, with sinks that often didn’t work and poor ventilation. Nobody held the slumlords accountable for not fixing the faulty ventilation, lack of running water and broken windows. These places were not set up to safely house vulnerable teens. Creeps would grab me and other young women in the hallways or try to lure us with free beer or weed, or worse, try to break into our rooms at night. Our complaints to the hotel manager were met with eye rolls or, even worse, more lecherous advances from the hotel staff themselves. For me, the unpredictable and unregulated structure of these accommodations was just another part of the street life I’d become accustomed to.

I stayed in one of the “better” SROs, known as the Piccadilly, on Pender Street. It shuttered in 2007 for fire-code violations. It was closer to Granville Street and farther from Main and Hastings, where then, like today, all the street action is — a noisy and frantic scene that includes a kind of open-air drug market where people openly smoke crack with makeshift pipes and shoot opioids. It is a place that I see as one manifestation of deep trauma, where hurt people are in need of mental, emotional and spiritual healing, accessible and safe health care, and proper housing that society is failing to provide them.

As a street kid, I was living with my own trauma and was coping the best way I could. A friend I grew up with recently described the time we spent on the street, when she was 13 and I was 17, in this way: “We were reality averse.” When I told her I wasn’t sure how much I wanted to divulge in my book about our lives then — in particular our coping mechanisms — she told me, “It’s your book, you should do what you want, but if you’re trying to tell your story, drugs were sometimes a part of it.”

It wasn’t so much that we were addicted, but we took whatever we could get our hands on, she explained. Another friend reminded me that we were dealing with a lot of trauma (from constant abuse, assault and abandonment), but we were also teenagers experimenting with life.

Adapted with permission of the publisher from the book Unbroken: My Fight for Survival, Hope and Justice for Indigenous Women and Girls, written by Angela Sterritt and published by Greystone Books in May 2023. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Books, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: