Tracey Lindeman only had about one bearable, relatively pain-free week per month for nearly 24 years.

The Montreal-based journalist is one of an estimated 400 million people assigned female at birth globally who live with endometriosis, a chronic inflammatory condition wherein endometrial-like tissue grows outside the uterus.

The tissue can fuse to organs throughout the body including the ovaries, pancreas, bladder, lungs, bowel and in some very rare cases, the brain. With the errant tissue comes extreme pain, heavy and painful periods, nausea and difficulty getting pregnant. Some suffer collapsed lungs around their menstrual cycles and many, like Lindeman, are prescribed hormonal birth control that hardly helps the pain and can send them into deep depressions.

“A typical month for me was like a week of really terrible premenstrual syndrome, then seven to ten days of bleeding, and then a week to recover,” Lindeman told The Tyee. “So I really only had one good week a month.”

Since her pain began at age 14, the dismissal, denial and silencing Lindeman faced at every step of her search for effective treatment exacerbated her agony. Even as her eventual hysterectomy brought some relief, the fight to get there opened new wounds.

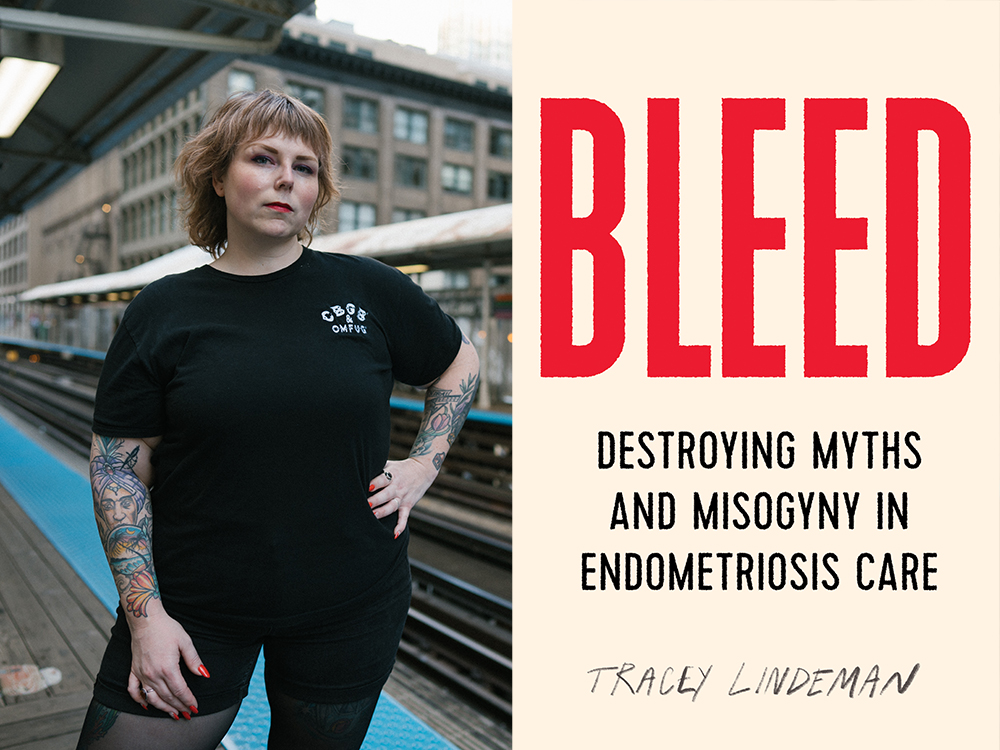

Out today with ECW Press, Lindeman’s first book, Bleed: Destroying Myths and Misogyny in Endometriosis Care, is a salve to the isolation and blame other endometriosis patients face on top of their pain.

Part memoir and part reported non-fiction, Bleed chronicles a diverse array of patients’ fights for relief and their shared struggles against the entrenched medical misogyny, racism and fatphobia detailed in Lindeman’s extensive research.

From gynecology’s roots in the violation of enslaved Black women to funding structures that disincentivize family doctors and OB/GYNs from treating endo, Lindeman argues that every facet of the medical system is working against patients’ goals of a pain-free life.

The Tyee spoke with Lindeman about Bleed and the complicated solace she has found in sharing her story.

The Tyee: How did you begin to find an inroad into this deep and multi-layered topic when you have been living and breathing its pain for so long?

Tracey Lindeman: My story for the longest time just kind of felt like one long tale of pain. And when I finally got in to see that surgeon who agreed to do [an excision and hysterectomy], I had an arc to my story. It wasn't just endless suffering. As a journalist, it was also like, how are people not talking about this thing that affects at least ten per cent of people assigned female at birth? How is this allowed to be considered normal? Millions of people are suffering needlessly for no reason other than misogyny really, that's the story of women, but this is like a really tangible example of that experience.

Endo patients who are receiving the bare minimum of care are still suffering debilitating pain, collapsing lungs, depression and infertility, which you argue is a form of violence. How did you interrogate discrimination against endo patients when it is so normalized and seemingly mundane?

A big part of it was that my understanding of feminism and feminist issues has matured over time. I realized so many of the things that felt so personal, and were so personally harmful to me, were actually little pieces of the system at work. I felt a shift from feeling anger towards myself, or not being able to figure out how to help myself, and more towards anger at the system. It got me thinking I should maybe place the blame where it belongs, instead of internalizing it like I had done for so long and like other endo patients do as well.

One of the major takeaways I had from your book was that fatness and mental illness and "hysteria" stereotypes are all still used to blame and stigmatize people for their own endo diagnosis and suffering. Has the terminology endo patients face changed?

I don't think the idea that women are hysterical is gone at all, I think it's just that we've changed the way that we talk about it to make it seem more insidious, more socially acceptable. And so it gets even more deeply entrenched into our health care, because when the terms constantly change, we have to reorient our understanding of what it really means.

The label is in all the bad advice we get. I’ve been described as depressed, anxious, stressed, told, “you just need to relax. You need to exercise. You need to lose weight.” To be clear, there are benefits to doing all those things, but they don't fix you. And so every time your menstrual cycle comes back around, and [the symptoms] hit you in the face, it's a whole new offense. And when you're a bigger person, it's so easy for doctors to just blame everything on your weight, even when you are there for something that is clearly in need of immediate medical attention.

You detail how racism and psychosocial factors impact how Black people, for example, present clinically with endometriosis. How do you begin to address those differences in treatment and symptoms between people of different races while interrogating the role of white supremacy in endometriosis care?

By recognizing that gynecology exists because of white supremacy. Prior to the establishment of gynecology as a discipline in the mid-1800s, the people that took care of women's health were mostly healers, midwives and often women of colour and immigrant women. Then medical colleges targeted midwifery as a thing they could dominate, because it was one of the most lucrative medical services at the time, because people are having babies all the time. At this point in time doctors are not necessarily well regarded in society. They were still seen as quacks. And so this shift is really wrapped up in the professionalization and institutionalization of medicine. And taking birthing and women's health away from midwives was done by villainizing these women of colour who were performing these services in a white supremacist society.

With so much evidence about the impacts of weight stigma and racism and also what good endometriosis care can look like, why do you think these patterns of poor treatment and neglect and discrimination persist? Is it willful?

I think it's willful in the sense that people aren't doing the work required to think critically about their role in the system. And I think it's more out of laziness and malevolence. Doctors are very busy, but they're not keeping up on the literature or advocacy about endo, so when you get to see them, they kind of rely on these old tropes that have been debunked and disproven since they were in medical school. And the health-care system doesn’t require education on this or for doctors to be trained to treat it. There was a study a couple years ago that showed 60 per cent of general practitioners or family doctors feel uncomfortable treating endometriosis because they don’t know a lot about it. That's a huge problem. But then even many OB/GYNs don't know anything about endo either.

When seeking your hysterectomy, you write that you felt the future potential children you didn’t even want were prioritized over your own goal of a more pain-free life. Did knowing you didn’t want children make those conversations easier? And why is it still so hard for people who want a hysterectomy to treat their endo to get one?

If anything, it made it harder to convince my doctor to actually listen to me when I said, “I want this surgery and I don't want kids and I know I never will.” And she was like, “No, you're gonna change your mind about kids.” She was catastrophizing the outcomes of making that choice for myself. But if I wanted to, I could go next door to a plastic surgeon and have someone take off my face and put a new face on. So how are some people allowed to make those choices and other people aren't?

When you’re being asked if you’re pregnant or could be or are trying at every medical appointment, that's just one little way that paternalism manifests itself. On the flip side, people who do want kids who haven't given up on the idea of having kids with a disease like endometriosis or polycystic ovary syndrome is a horrifyingly tragic circumstance, people who are devastated by that. But that angle is covered a lot in the literature and in endometriosis care in general. And that's why I did lean a lot on my own experience of being child free, because I felt that my perspective had not really been shared much at all in endometriosis talks.

Why are endo patients expected to endure such a high burden of serious side-effects from birth control as the first-line of treatment? The pill can really negatively affect some people as you detail, but I get the sense it’s seen as the cost of doing business for endo patients who don’t ask for a hysterectomy or want to be in —

Terrible abject agony? Yeah, isn't that crazy that we just are like, “Oh, just take this pill, and you'll be totally fine.” Number one, the pill might lessen some people's symptoms, but it doesn't really do as much as doctors like to believe that it does. But also that we're giving children, people whose brains are not developed, a drug that messes up their hormones and their brains. How is this not causing international alarm? I'm not saying that birth control was terrible or that I'm permanently brain damaged because I took birth control. But none of the risks and side effects were really discussed with me. And when I felt them, I was told that it was my own psychology at fault.

I believe that birth control was critical to women's liberation and it's extremely important to have any kind of reproductive control you can have, but the pill has barely changed since the 1950s. Like why haven't they created a birth control pill or IUD or implant or shot that doesn't destroy people's lives?

It sounds like this raises concerns around the informed consent endo patients are afforded.

Specifically in situations like endometriosis, like there's almost no informed consent at all. Unless you ask and you're personally knowledgeable about the terminology, they won’t even explain the surgeries in a way that you understand. Or why a lot of surgeries like ablation, which is basically like the burning of your uterine lining, are recommended when endometriosis is specifically characterized by growth of tissue outside of the uterus. Why does that come before surgical excision, which experts consider the gold standard? How is that informed consent?

What was the most surprising thing you learned in your research? Did anything truly shock you?

Just how much information is actually out there about endo, and yet we treat it like it's this weird, rare, mysterious disease. And that we let doctors and institutions off the hook for being responsible for learning about it. At least 10 per cent of people assigned female at birth have endo and another 10 per cent have polycystic ovary syndrome. A third of people with vaginas have pelvic pain with sex. We've just let our private parts become this mystery to medicine, and because it's vaginas we're somehow okay with it not being talked about.

What would good health care for endo patients look like? And what would have to change in the health-care system to make this happen?

It’s a difficult question to answer because I don't know if people who are currently practising medicine can be reformed. I think it has to happen when people are still young and impressionable. What I want is for all kinds of doctors and all types of health-care practitioners to actually collaborate with their patients, to listen to them. And to understand that living with a chronic disease every day for years of your life is a form of credible knowledge, and that doctors should take this knowledge into consideration when treating people's pain and their suffering.

There is this tendency to believe that women exaggerate pain, like that's a documented thing in research and medicine. So what if you are? You should still get help. It's as simple as that. And we need to educate people about their bodies and not just what the parts are called. So many people start developing endo symptoms when they get their first periods around age 10, 11 or 12, and that's often when you start feeling all the pain. Everyone around me told me that being in agony was normal. I didn't know that it wasn't supposed to be like that for years.

We’ve seen a resurgence of advocacy and awareness about endo and other dismissed conditions be facilitated on social media. But we've also seen that shared community for people slide into slippery "wellness" territory that feels a bit predatory and isn’t always evidence-based. What is the wellness crowd offering people that conventional medicine isn't?

Wellness is a $4 trillion industry right now and I think it is based on people who are in some form of suffering or pain. They prey on the gaps in the medical system that leaves these people feeling so misunderstood, so unheard, so desperate for help.

I’ve certainly bought plenty of wellness products or wellness services to try to make myself feel a little bit better. I felt like I had to do it myself because no one in the medical system was willing to help me. It's so expensive, even in a place with so-called universal health care, to be sick, to have a chronic pain condition. People think that we're just leeching off the system, that chronically ill people are just obsessed with being sick and just need to suck it up. But why do I have to live in agony? Why is this normal? No one should have to live like this.

What do you hope the legacy of this book will be? How has it been received by fellow endo patients?

Yesterday, I got an email from someone who I interviewed for the book. She was talking about how she kept going back to the doctor to ask for a hysterectomy. And the doctor was like, “No way.” She said being interviewed by me for the book made her push back and advocate for herself and she actually was accepted to have the surgery she wants. It's incredible. I'm so honoured to have been able to help even just one person get the help that they want and that they need. So if anything, I just hope that I push patients to not accept bad care, and just push to be heard, to be listened to and to feel like you have a right to be here and you have a right to not be living in pain. ![]()

Read more: Health, Books, Rights + Justice, Gender + Sexuality

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: