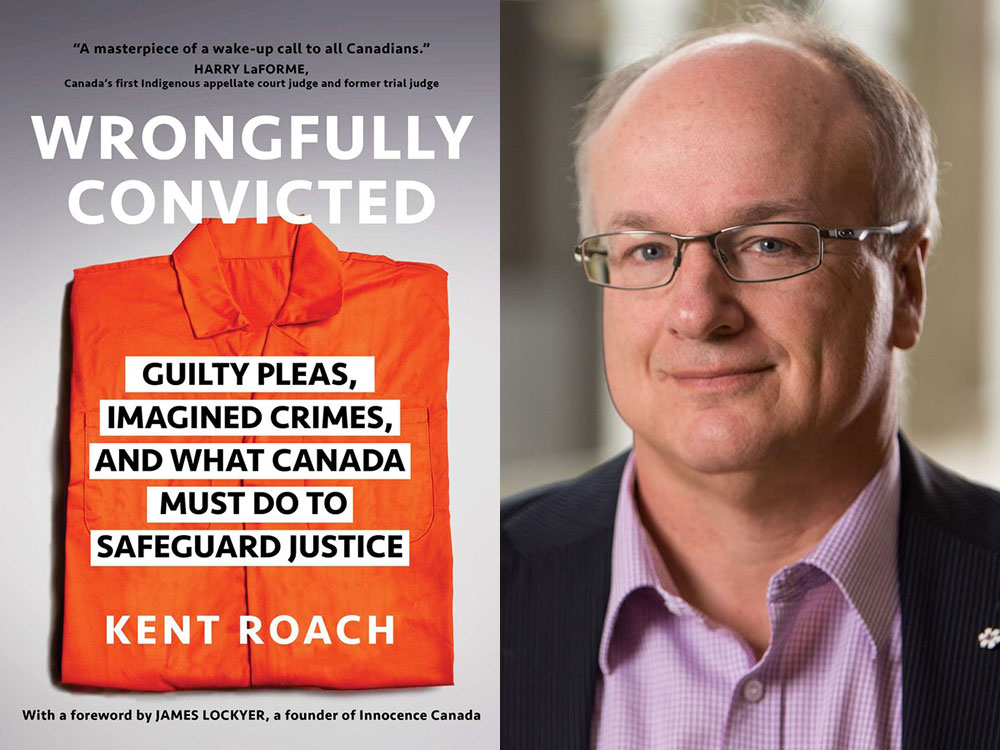

- Wrongfully Convicted: Guilty Pleas, Imagined Crimes and What Canada Has to Do to Safeguard Justice

- Simon & Schuster Canada (2023)

“Correcting a wrongful conviction is like climbing a very high mountain,” Kent Roach writes. “It takes time, funds, support and volunteers who know the path.”

For 35 years, Roach, a professor of law at the University of Toronto, has been studying, teaching and writing about wrongful convictions. On those daunting slopes, he is one of this country’s most experienced climbers, pursuing a path not for the faint-hearted or impatient.

“No system run by humans can be perfect,” Roach acknowledges. But he worries that wrongful convictions get little public attention, owing to a news cycle where stories come and go at warp speed, and investigative reporting struggles to survive.

What Canada needs, Roach has long argued, is an independent commission to look at possible wrongful convictions. Last month, the federal government finally got around to introducing legislation in the House of Commons that would establish just such a tribunal.

Unbalanced scales

After spending 23 years in prison for a murder he did not commit, David Milgaard offered these chilling words, “This could happen to you.”

If it does, know the odds are vastly stacked against you.

Under the present system, when appeals have been exhausted, the wrongfully convicted person has to find lawyers or volunteers to agree to take on an innocence project. Fewer than 20 completed mercy applications are submitted to the federal minister of justice each year. Very few succeed. Only about 20 of these cases have been overturned since 2002.

Correcting or preventing a wrongful conviction costs money. But far more resources are concentrated elsewhere in the system. “The money spent on defence is dwarfed by the money spent on policing, experts and prosecutors,” Roach says. In an adversarial system, this seems patently unfair.

In 2021, the Federation of Law Societies of Canada expressed hope that a permanent independent commission to investigate claims of miscarriages of justice would have adequate funding. Innocence Canada had 92 active cases in 2002. The organization spends half of its time trying to raise money to fund costs for private investigators, travel, forensic testing and experts. They know there are thousands of dubious cases out there, but can only fund the most egregious ones.

Canada’s best known wrongfully convicted persons include Milgaard, Guy Paul Morin, Steven Truscott and Donald Marshall Jr.

Milgaard and Morin were eventually proven innocent by DNA, which established who the real killers were in their cases. Milgaard had to wait 28 years for his exoneration, which finally came in 1997. Although Morin was exonerated by DNA in 1995 for the murder of nine-year-old Christine Jessop, it wasn’t until 2020 that DNA finally revealed that the killer was actually a Jessop family friend, who had committed suicide in 2015. The RCMP maintains a DNA data bank with over 400,000 profiles, but DNA evidence is also subject to interpretation, and therefore human error.

One of the key recommendations that Roach makes in this book is the call for full disclosure from the prosecution. He argues convincingly that defence teams should have better access to police systems of information about crime victims and possible other suspects.

There is, of course, immense public pressure to solve violent crimes, which can lead to coerced witnesses and racist bias. Many Indigenous people have good reason not to co-operate with the police. Some judges are less inclined to believe Indigenous people when they testify. Indigenous people are the most at risk for wrongful convictions, but their cases usually receive little media attention. Often they lack the funds to mount a proper defence.

Nor does the justice system like to admit mistakes, partly because it is so difficult to correct them, and partly because it is so embarrassing. Confirmation bias or tunnel vision of the police has led to wrongful convictions when authorities focused on one suspect to the exclusion of other possible targets.

‘God’s pocket’

A case in point is one with which I had personal experience. Police were ready to believe that 17-year-old Mi’kmaw Donald Marshall Jr. was a killer. They clung to that assumption rather than investigate information that a middle-aged white man, whom Marshall described, had actually stabbed Sandy Seale to death in Sydney, Nova Scotia in 1971.

Marshall had also been slashed during the attack that killed his friend, and had even flagged down the police to ask for help. Despite the fact that just 10 days after Marshall’s conviction the real killer’s companion told the police that Roy Newman Ebsary was the guilty party, Marshall remained in jail for more than a decade. Ebsary was subsequently convicted of Seale’s murder.

The Sydney police so wanted to believe Marshall was the killer that they essentially framed him. They simply told the man who gave them the name of the real killer that the case was closed. Eleven years of the teenager’s life was snatched away unjustly.

It is worth repeating a few of the awful facts. Young witnesses were coerced into saying they had seen Marshall stab Seale. Twelve white men decided his fate in a murder trial that lasted a single day. English was not Marshall’s first language, and he told me that the court experience was so foreign to him that he was not even sure which lawyer was prosecuting him and which was defending him. Convicted in 1971, Marshall spent 11 years in prison before he himself found new evidence that would eventually exonerate him.

Even then, he was blamed for his own wrongful conviction by judges on the Nova Scotia court that overturned his conviction. A landmark 1989 royal commission found that police, judges and even Marshall’s own lawyers had contributed to his wrongful conviction.

How did the innocent teenager see himself through the entire ordeal? “I was a toad in God’s pocket,” he told me.

Built for wins over justice

In Canada, 30 per cent of the prison population is Indigenous, despite accounting for only five per cent of the general population. Of the 83 entries recorded in the Canadian Registry of Wrongful Convictions, 14 people are Indigenous. Roach poses a great and troubling question in his book: “But how many Indigenous men and women have been wrongfully convicted and do not have the support, funds or faith in the system to have gone through the long process of correcting their wrongful convictions?”

It should be remembered that not only is the individual directly involved in a miscarriage of justice greatly harmed, but their family members are as well. Donald Marshall Jr.’s whole community suffered from the stigma of his wrongful conviction, including his father, Donald Marshall Sr., who was Grand Chief of the Mi’kmaw Nation at the time.

One of the most profound points Roach makes in Wrongfully Convicted has to do with the way the system is built. He points out that it concentrates more on winning the case than on seeking justice. “No trial is really about discovering the truth,” he writes, rather it is a contest between the prosecutor and the accused in a purely adversarial system. Acquittals are rare — about three per cent of all cases.

Volunteers who work on innocence projects operate without legal powers or public funding, so convictions are extraordinarily difficult to overturn.

Some innocent people who believe the system is going to crush them anyway plead guilty in order to receive a lesser sentence. Of the 83 people on the innocence list, 15 are false guilty pleas. This disadvantaged group includes women, Indigenous and racialized people, and they all bear a disproportionate burden of this variety of wrongful convictions.

And then there is the category of “imagined” crimes. In the Canadian Registry of Wrongful Convictions, 22 of the 83 names on the list fall into this category. Young children died by accident or unknown causes, but their caregivers were convicted of murdering them. Roach reminds his readers of one infamous case where several infanticides were based on inept and mistaken “expert” testimony by Dr. Charles Smith at the Hospital for Sick Children.

Eight people pled guilty to killing their young children when faced with Smith’s expert testimony, partly because Smith was so self-assured and convincing on the stand. In 2021, the Journal of Forensic Sciences published a controversial study based on 1,000 baby deaths from 2009 to 2019. “Forensic pathologists were more likely to classify the deaths of Black children as homicide, and the deaths of white children as accidental.” Background information offered by police to forensic pathologists, often while they were conducting an autopsy, was also found to be an influence on their conclusions.

In an autopsy done in 1997, Smith determined that a seven-year-old girl had died from multiple stab wounds. Her mother spent two years in pretrial detention, all of it in segregation for her own protection. The child had in fact been killed by a dog, a pit-bull. Smith had clinical but not forensic training, even though he testified in court as a forensic expert. In 2011, Smith lost his license to practice in Ontario.

Fixing the system

Wrongfully Convicted is much more than a compendium of horror stories about how innocent people really do go to prison. It also points out some of the improvements in the system aimed at preventing wrongful convictions that have come from belated justice for wrongfully convicted people. For example, the inquiry into the wrongful conviction of Donald Marshall Jr. created an Indigenous law institute and a program to encourage Mi’kmaw and Black students to attend law school.

The commission concluded that mandatory pre-trial disclosure would have prevented Marshall’s wrongful conviction. The inconsistent statements of witnesses who lied in court would have set off alarm bells, but Marshall’s lawyers did not ask for disclosure. Instead, they told the jury that the prosecution might as well have had cameras set up in Wentworth Park on the night Sandy Seale was murdered.

This lamentable declaration was a reference to the alleged eyewitness testimony of two teenagers, John Practico and Maynard Chant. Both were on probation at the time of the Seale murder, one for selling drugs, and the other for stealing milk bottle money. Both quickly recanted their stories when I knocked on their doors more than a decade after Marshall went to prison based on their lies.

For Kent Roach, and all the others who fought for so long to improve the justice system, there has been a measure of vindication, though it has been slow in coming.

In 2008, the inquiry into David Milgaard’s wrongful conviction recommended an independent commission be created so there would be fewer inquiries needed. Milgaard had spent 23 years in prison, and then had to wait five more years for DNA to exonerate him in 1997, using evidence carefully preserved by an amazing court clerk who believed he was innocent.

Once released, Milgaard spent his days helping other people find exoneration. Like Marshall, Milgaard was 17 when he was sentenced to life in prison. And like Marshall, he steadfastly protested his innocence, even though it negatively affected his possibility of parole.

In 2019, the government of Justin Trudeau committed to replacing the system of ministerial mercy of the crown with an independent commission to “improve access to justice for potentially wrongly convicted people.”

Now, three years later, the Trudeau government has introduced legislation for “Milgaard’s Law.” The bill will finally establish an independent commission to review and decide which criminal cases should be sent back to the justice system.

Justice Minister David Lametti had promised David Milgaard he would “make the system better” when they met in 2019. Both David Milgaard and his mother are now dead.

Though Milgaard didn’t live long enough to see it, his case finally changed the system along the lines recommended by relentless advocates for justice like Roach and the Canadian Registry of Wrongful Convictions which counts him a contributing member. The organization’s symbol is a mountain.

Donald Marshall Jr. also was missing from celebrations of the introduction of the long-anticipated bill in February. He died in 2009. I imagine that if he were still among us, the toad in God’s pocket would have given a big bear hug to Kent Roach. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: