You’re in prison, locked up for a horrible crime you didn’t do.

As long as you maintain your innocence, you’re going to stay behind bars.

But if you confess to a crime you didn’t commit, the Parole Board of Canada will throw the prison doors open.

The demand for confession — even from the innocent — is a problem in Canada and around the world, one that criminal defence lawyer Rachel Barsky and Adam Blanchard explored in a report for the Criminal Defence Advocacy Society.

The report released in the fall, Preventing Parole, says there are more than 50 acknowledged wrongful conviction cases in Canada. Innocence Canada has helped exonerate 23 people since 1993 and is reviewing another 81 cases. It’s operating with limited resources; there are almost certainly more.

For a criminal justice system that handles more than 300,000 cases per year, that’s actually remarkably few wrongful convictions.

Which is no comfort for the people locked up for crimes they didn’t commit. And who are facing immeasurably grimmer lives because the parole board insists that offenders acknowledge their guilt if they want to be released.

From teen to middle-aged behind bars

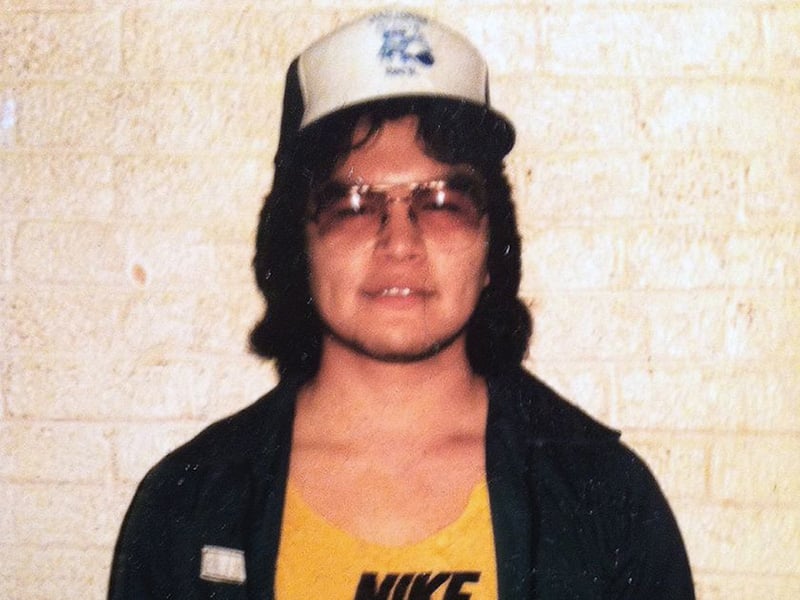

People like Phillip Tallio. When he was 17, Tallio was charged with the first-degree murder of a 22-month-old girl on the Nuxalk Nation reserve beside Bella Coola, B.C.

“No physical evidence implicated Mr. Tallio in the crime,” the report notes. “No direct, or valid circumstantial evidence existed.”

Tallio has always denied killing the child. He pleaded not guilty to first degree murder. But partway through his 1983 jury trial, the teen pleaded guilty to second-degree murder.

Tallio says his lawyers made the decision, and he didn’t understand what was happening, let alone approve the plea. The lawyers probably thought it made sense. Jury trials are risky, and a first-degree murder conviction would mean at least 25 years in prison. A plea to second-degree murder would allow Tallio to be paroled in 10 years.

Except that 35 years later, Tallio is still in prison. Every time he has applied for parole for the last 25 years he has been turned down because he won’t confess to a crime he didn’t commit. (The Vancouver Sun did a powerful series on the case.)

Barsky and Blanchard note that an inmate’s unwillingness to admit guilt has broad repercussions. Those who maintain their innocence are less likely to be approved for escorted day absences — to attend a family member’s funeral, for example. And they are often denied access to Corrections Canada programs because they won’t admit guilt. The failure to complete the programs then becomes another reason they are denied parole.

It’s obviously most unfair for those wrongly convicted.

But does it really serve a purpose to demand that anyone admits guilt as a condition of release?

A family consumed by the parole conundrum

I first became aware of the issue through the case of Derik Lord. In 1990, his friend Darren Huenemann enlisted Lord and David Muir — all high school classmates in Saanich, B.C. — in a plan to kill his mother and grandmother.

They did. The crime was horrific, with the women left dead and covered in blood.

Eventually, all three were convicted of first-degree murder. Lord and Muir, not yet adults, were eligible for parole in 10 years; Huenemann, 18 at the time of the crime, was not eligible for parole for 25 years.

After 10 years, Muir admitted guilt and was released on parole. Lord, who maintains his innocence, has applied for parole at every opportunity since 2002. He remains behind bars.

The evidence against all three leaves little doubt that Lord was guilty.

But it’s still remotely possible he’s innocent. Or he might have lied to his family initially and feels compelled to stay with the story. (His family has been consumed by the effort to prove his innocence.)

“Denial may serve to protect the offender’s family from stress and embarrassment,” the Preventing Parole report notes.

The real question should be whether demanding a confession makes us safer. Will an offender who refuses to admit guilt be more likely to commit other crimes?

No, say Barsky and Blanchard. “Denial is not a major risk factor for violent, sexual or general offending,” their research found.

Predicting the likelihood that someone will re-offend, and identifying the factors that will reduce the risk, is the central role of the parole board.

We could be doing a better job, the report argues. It also recommends that denial of guilt no longer be used as a reason to deny parole or access to programs, among other useful proposals. And it called for a new independent body to review innocence claims, like the U.K.’s Criminal Cases Review Commission.

A system that’s not working

And the report noted that the entire system seemed to lack any formal, evidence-based approach to assessing inmates and preparing them for release. “A recurring theme throughout Preventing Parole has been the lack of consistency amongst inmates’ experiences and treatments.”

Which should alarm us. In 2017, almost 40,000 people were behind bars in Canada, 14,425 in federal custody.

Those federal prisoners cost us an average $115,000 a year. If we can do a better job of preparing people for release we can help them, save money and reduce crime.

We’re not doing well now. Stats on recidivism are hard to find, but one study found more than 40 per cent of released federal inmates were convicted of another offence within 12 months.

Sentencing is supposed to reflect basic principles — expressing our condemnation of the crime; deterring the offender and others from future crimes; and protecting the community by locking up people who pose a current danger (and ideally reduce that risk through programs during their incarceration).

The demand for a confession — especially a false confession — does nothing to achieve those goals. And it leaves people like Tallio trapped in prison because they refuse to lie just to satisfy the parole board.

The report raises much larger questions about our approach to dealing with offenders. It should trigger a policy discussion that goes far beyond the issue of demanding confessions. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: