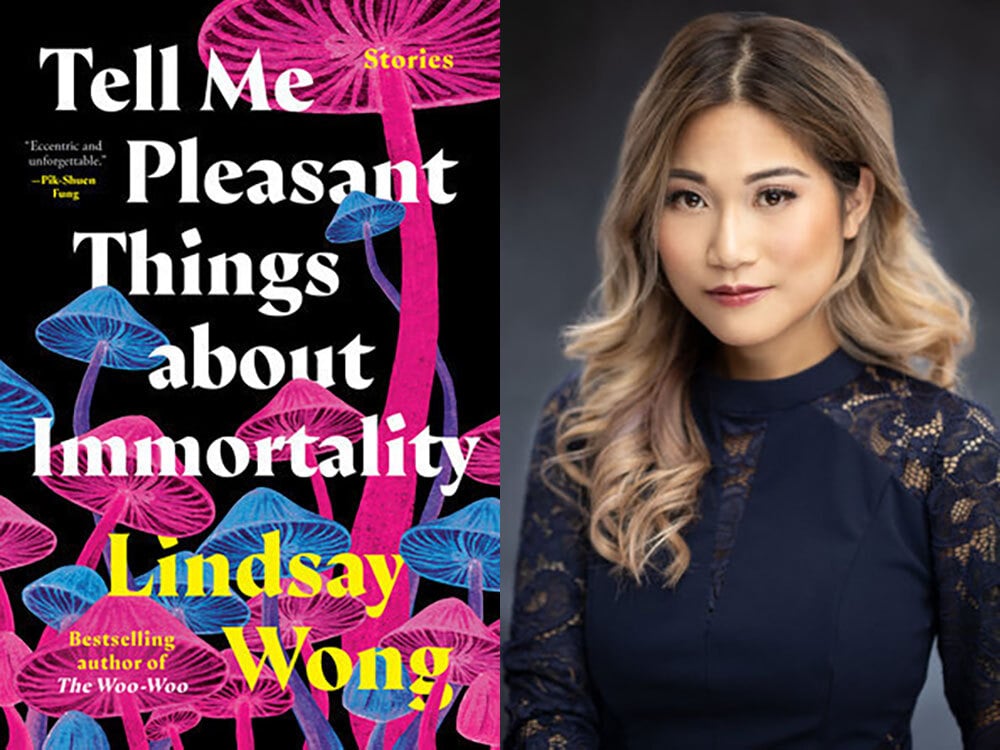

- Tell Me Pleasant Things About Immortality

- Penguin Random House Canada (2023)

Tell Me Pleasant Things About Immortality is a collection of short fiction that embraces some of the most satisfying elements of its genre. Through speculative fiction set in early China and immigrant horror stories set in contemporary Metro Vancouver, author Lindsay Wong surfaces widely felt, underrepresented dimensions of the Chinese experience that shape our lives and how we think about ourselves. She approaches food and sex, body image and self-esteem, and work and loyalty with a clever frankness and a delight in the absurd. The result is a funny, true and subversive collection whose surrealism shocks the muck of everyday life into bright, astonishing relief.

Wong lived in Vancouver and was the Vancouver Public Library’s 2021 writer in residence before moving to Manitoba to take up a position as a creative writing professor at the University of Winnipeg. This is her third book, following a buoyant young adult novel that succeeded her acclaimed 2018 memoir The Woo-Woo: How I Survived Ice Hockey, Drug Raids, Demons and My Crazy Chinese Family.

Wong’s memoir on mental illness and immigrant family dysfunction won the 2019 Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize and was a finalist for the 2018 Hilary Weston Writers' Trust Prize and Canada Reads 2019. Newsweek, CBC Books, the Globe and Mail and Quill and Quire named it one of the best books of 2019. By all accounts, the book was a resounding success. But in 2021, Wong told Michelle Cyca in a Tyee interview that she had a hard time finding a home for it with publishers.

“I had 13 rejections, and mostly it was because it was ‘too dark,’ which was hard to respond to,” Wong told Cyca in The Tyee. “It’s my life, I don’t know what I could do to make it less dark. Sometimes I got ‘too niche,’ which could be a coded thing — not white enough, not mainstream enough. And then, there’s always ‘too weird.’ I always get ‘too weird’ on my writing. What can I say? It happened! Real life is sometimes stranger than fiction.”

In Tell Me Pleasant Things About Immortality, surrealist fiction brushes up with the truth. The influence of the West Coast is felt throughout the collection. We feel the damp claustrophobia of the city in a twisted East Vancouver teen romance that culminates on the shores of Wreck Beach, and the drifting tension of the suburbs in a series of iPhone notes app diary entries by a young gay man working in a Coquitlam jail. In a story whose protagonists congregate in the kitchen of “the third best noodle shop in the Asian food court in Crystal Mall, Burnaby,” we meet a pair of siblings and the ghost of their grandmother, who continues to hover over and berate them, even in death.

Though the stories dance on the edges of campy surrealism, it’s easy to forget these are works of fiction because the characters and their circumstances feel so familiar. They are lonely young people parenting their aging immigrant parents, painfully comparing themselves and their low wages to their wealthy high school friends who are married and working as bankers. They are couples shouldering the weight of their parents’ expectations, escaping to their bedroom to smoke a joint and share a teacup of whiskey.

Wong’s closely observed writing mines the depths of a culture that constantly betrays and contradicts itself, shedding light on the dissonant forces that shape Chinese identity and families. The stories take aim at the relentlessness and brutality at the heart of many immigrant households, speaking to the ways in which poverty, scarcity and desperation shape our most important relationships.

In a scene from “Noodley Delight,” the aforementioned story featuring a trans teenager and their little brother haunted by the ghost of their dead grandmother, the family is getting ready to leave the house for the mall. “I change out of my polka-dotted pyjamas into a soft, flowy skirt,” the narrator says. “Grandmama stalks me down the hallway to my bedroom, gagging at my outfit, her eyes twitching like spazzy Christmas decorations.

‘Boys don’t wear dress,’ she snaps in her wild animal Mandarin. ‘Kyle, get me purse. Ernie, find me walking shoe. The one your mother chose for the funeral are shit.’”

In a context where the world is relentlessly unkind to them, Wong’s characters are hard on each other and harder on themselves. They internalize the racism, queerphobia and model minority projections of their surroundings. They conflate thinness with beauty and fatness with ugliness, all while consumed by a bottomless physical and emotional hunger that sees them betraying themselves and each other. In the Crystal Mall noodle shop, “Me and Ernie sit on stumpy plastic stools and slurp, competing to see who can chomp the loudest. The noodles look like bloated slugs, unholy and unappetizing, just like us.”

The experience of reading the book features successive jolts of recognition, grief and joy. There’s a refreshing canniness to Wong’s writing that challenges readers to think beyond what we assume we know about Chinese experiences and Asian-Canadian literature. She continues a tradition of this work also carried by Chinese-Canadian writers like Evelyn Lau, Jen Sookfong Lee, Madeleine Thien and Nancy Lee, who Wong read when she was growing up.

With humour and brass, Wong pushes against limiting, stereotypical assumptions that can be assigned to work by Chinese authors, by both white and racialized audiences. Her writing refuses the notions that Chinese people must be nice in order to be worthy of care, and that filial piety and a cohesive family unit are the only things worth fighting for. The oft-examined plentitude of unsolvable strife between generations in Chinese-Canadian fiction, for example, is not painted as something to be mourned, but met with a compassionate shrug: “Separated by the 21st century, life and death, not to mention clashing cultures and West Coast slang, could she ever understand?”

The work is magnetic because the pull of love, just out of reach, propels everything. There’s beauty and terror in this. After all, Wong writes, “Unrequited family love is a burden.” ![]()

Read more: Books, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: