Directed by B.C.-based filmmakers Tamo Campos and Jasper Snow Rosen, the documentary film The Klabona Keepers (2022) is named after the sacred waterways which its protagonists are fighting to protect. The film follows a group of Tahltan Elders as they take a stand for the Tl’abane (Klabona), the sacred headwaters of the salmon-bearing Stikine, Skeena and Nass rivers.

While the story of Indigenous grannies stopping resource extraction companies is inspiring in of itself, another noteworthy aspect of this film is its deep commitment to honour and uplift voices of the community. Developed in full collaboration with the Elders, The Klabona Keepers offers a significant example of how media producers can work with community to tell their own stories.

The Iskut community welcomed Campos and Snow Rosen into their lives in 2012. For the past decade, the filmmakers have worked to capture and document their stories to culminate in a remarkable portrait of generational healing, collective resistance and radical hope that offers an exciting contribution to documentary film.

By establishing this film project through longstanding reciprocal relationships, this process challenges dominant traditions of media production which are often problematic because they can be extractive in nature.

Located in northern B.C., the sacred headwaters are one of the largest intact freshwater ecosystems in North America. This stunning region is home to moose, grizzlies, stone sheep, mountain goats, caribou and wolves. However, the abundance of this land has not gone unnoticed by surveyors and developers. Mining companies refer to this area as “the golden triangle” for its generous deposits of gold, copper, gas and coal.

There could be huge corporate profit to be made if the communities were to stand down. “No money in the world will bring back the beauty of the land,” states Elder Rita Louie. “No money.”

This group of matriarch-led Elders make it clear that they are determined to protect this pristine land and water. They want to protect these ancestral hunting grounds for their grandchildren and great-grandchildren’s future and to honour their ancestors’ sacrifices.

“We’re rich with everything — with plants, with animals. That was taught to us by ancestors from years ago, how to survive by the land,” says Elder Bertha Louie.

The Klabona Keepers will resonate among many, especially members of rural communities grappling with conflict surrounding resource extraction and development, Indigenous law and the legacy of residential schools. The film captures the Indigenous-led blockades, standoffs and conflict with law enforcement, multinational companies and industry workers over a span of 15 years. The film skilfully shares perspectives from community members in support of the Klabona Keepers resistance as well as from those who are conflicted and work in the resource extraction industry.

“Most Indigenous people are not against development,” says Peter Jaketsa, a heavy equipment operator at the mining camps. “They know that jobs are needed to have the modern-day comforts that many desire, but there are limits to what we are willing to sacrifice.”

The Klabona Keepers touches upon the complexities of these matters, bringing accessible, politically-engaged storytelling to its audiences through archival and contemporary footage.

Beyond environmentalism, the film offers viewers an explanation of the legal processes that disempower Indigenous people in Canada. It explores how corporations rely on court injunctions to have the upper hand in legal proceedings and the flaws of government and industry-led consultation processes, which have been contentious among many other Indigenous land defense cases in B.C.

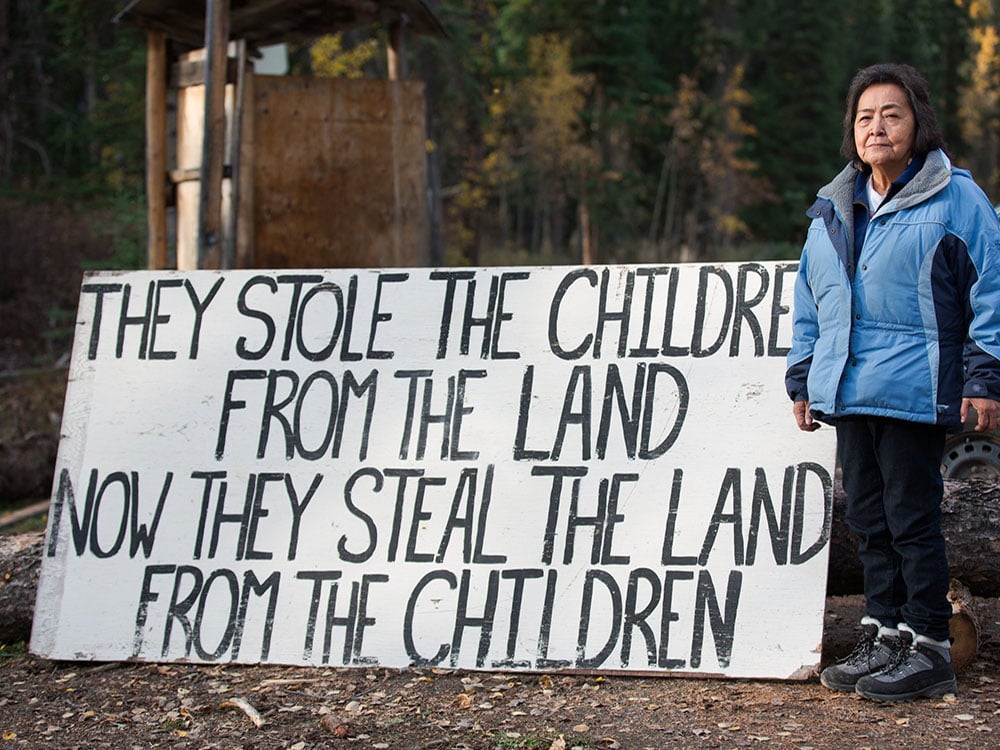

‘They stole the children from the land’

The film reveals motives behind the residential school operation in Iskut: land surveying by the federal government’s Department of Energy, Mines and Resources. Historical documents reveal collaboration between the Catholic Church, the Department of Mines and wealthy business owners working to displace families from the Klabona area.

These issues are interconnected with Canada’s ongoing relationship with the resource extraction industry. “They stole the children from the land, and now they steal the land from the children,” says community member Rhoda Quock.

The significance of Tahltan families now standing up to protect this land is not lost on viewers. One of the most moving parts of the film is watching Quock’s son, Caden, as he grows up with his grandparents at the blockades. Captured on film, Caden takes his first steps as a baby, learns to trap in the winter with his dad, confronts the CEO of Fortune Minerals as a 9-year old kid, and eventually walks the land on his own as a teenager.

“It gave me a lot of confidence to know I could do anything,” he says, speaking to these experiences. “[It] inspired me to protect this for the next generation to come.”

‘It completely changed my idea of what’s possible’

Filmmaker Campos addresses the “privilege… to be trusted with story” as someone from outside the community. While recounting the origins of working on this project, his fourth feature-length film, he shares memories of driving up Highway 37 and visiting Iskut for the first time.

Ten years ago, Campos and Snow Rosen stopped for ice cream at the Iskut gas station where they were invited to the Sacred Headwaters Music Festival. They were some of the only non-Tahltan people in attendance. Somebody spotted their cameras and asked them to come out to film their grandmothers who were trying to kick out a mining company from the headwaters. The filmmakers intended on visiting for three days and ended up spending seven and a half weeks filming videos to share with news outlets and social media.

“That summer, they were taking us out hunting and we were eating off the mountain that was proposed to be turned into an open-pit coal mine,” Campos shares. “We were camping on the mountain they were fighting for and [along with Elders and kids] trying to figure out how to stop this company that’s right there in a dignified and respectful way. It completely changed my idea of what’s possible if this group of grannies and kids were able to beat this company.”

By and for community

Four or five years into their visits to Iskut, Campos and Snow Rosen were asked to tell a deeper story through film based on the footage captured over the years. Campos recounts, “[Elders] started to say ‘You know you always released these really short clips for news, but they never tell the deeper story, and would you guys want to tell the deeper story?’”

“We trust them with this film because they have always taken our leadership,” says Quock. “They return every year and have taken on roles working with our youth.”

Campos and Snow Rosen agreed to take on the film as volunteers if the community helped to write it: “We spent four and a half months just going house-to-house with the Elders, having tea every day and trying to hash out ‘What is the story of the Klabona Keepers?’”

Campos recognizes how the film would’ve looked completely different without the community storyboarding process, weaving together each Elder’s individual perspective.

The Elders believed they really needed to dig into the past and address their own healing journeys. In the film, they speak to the traumatic impacts of residential school that impacted their ability to care for themselves and others. They needed to do healing work before they were able to step up and oppose these companies head on.

In light of the significant hardships each of them have overcome, the Elders’ confidence, bravery and love for the land and their grandchildren is striking. Spiritually and emotionally, this film is about far more than the protection of a remote ecosystem.

As an expression of gratitude for the time shared together, the filmmakers offered The Klabona Keepers as a gift to the Iskut community. The Elders own the film’s intellectual property rights and will retain proceeds earned from film screenings and events. They’ve decided that all funds raised will go towards youth programming within the threatened Klabona area to continue to empower future generations.

Campos and Snow Rosen’s tangible act of solidarity provides one inspiring example of how non-Indigenous people can stand with and support the lead of Indigenous communities on the frontlines. As a story of intergenerational community resistance and determination, The Klabona Keepers offers important lessons to consider the role of collective action in building a just future, together.

‘The Klabona Keepers’ will screen at the 2022 Vancouver International Film Festival on Oct. 3 and 5, with a free 12:30 p.m. screening on Oct. 4 for secondary school teachers to bring their students. Community screenings can also be requested through the filmmakers. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Film, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: