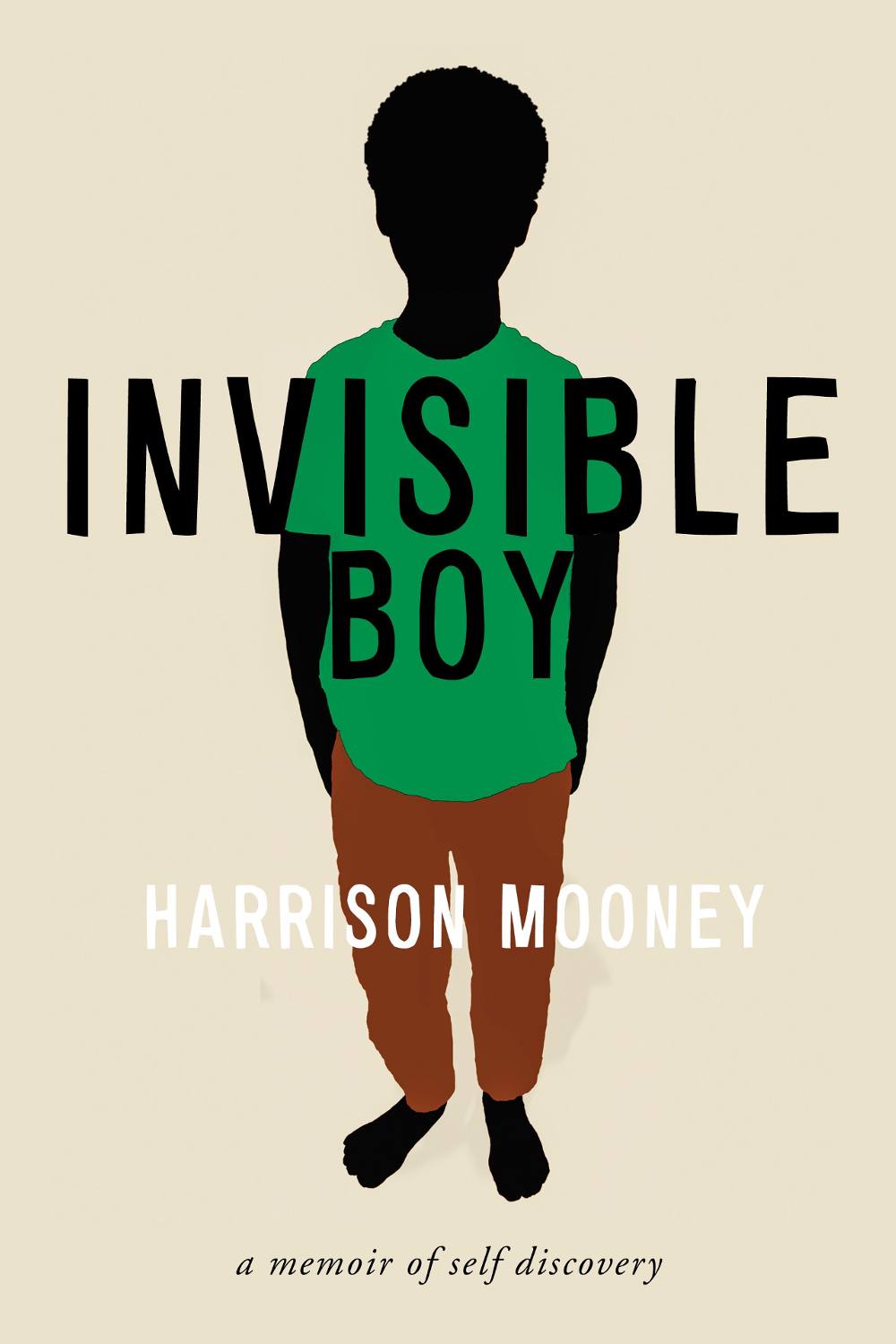

[Editor’s note: Vancouver journalist and author Harrison Mooney launched his first book this week. 'Invisible Boy' is a memoir published in Canada by Patrick Crean Editions, an imprint of HarperCollins. In it, Mooney explores the systemic forces that shaped his upbringing as the only Black adopted child in a white, devoutly Christian family in Abbotsford, B.C. The Tyee ran an interview with the author Tuesday. Today, read an excerpt from 'Invisible Boy.' At this moment in the book, Harrison is a young adult arriving at an adoption agency in Metro Vancouver to learn about his birth parents for the first time.]

The golden nameplate on the door read: BURDEN BEARERS INTERNATIONAL. The T was a miniature cross.

I couldn’t see inside — the glass was frosted — and I thought for a moment that the address I’d scribbled in pen on my palm might be wrong. So I turned away, roaming the zigzagging hall in confusion, past a therapist, a dentist and a hearing clinic, all of which were listed on the second-floor directory. The Hope Adoption Agency was not.

I had one foot in the stairwell when the door behind me opened.

Over here, Harry! Lynn Braidwood shouted, waving. The lady was a little teapot, short and stout, with a striking resemblance to Officer Frost, the Sunday School teacher from Gateway. They had the same silver hair, thin and short in supply, showing scalp — the same pale complexion, the same eggy frame. The two women could have been sisters. She ushered me in and I thought of her lookalike, leading the little boy, James, to his doom.

The little plaque confused me, I said, hanging my coat on the back of the door.

I’ve been meaning to change that, she said, grimacing playfully. We used to be Burden Bearers, back when you were born. But we’ve been Hope for nearly 20 years now.

It’s definitely a better name, I said.

I agree. You’re not a burden. Make yourself at home.

The office was set up like a living room, with multiple, floral-print sofas, arranged around an oval table. A dozen white women sat there, sipping coffee out of Styrofoam cups. Each one of them evoked, for me, my mother, and I thought of how close I had come to just leaving.

I’m so glad you chose to stop by, Lynn Braidwood said. I’m just finishing up with my group. I meet every week with some of the mothers I’ve worked with, women who took in Black babies — like you! I hope you don’t mind, Harry. I told them you were coming today. They’re very excited to meet you and, if you’re comfortable with it, they have some questions.

It felt like an ambush. Lynn Braidwood had invited me to come for 1:30, but according to a schedule I spotted on the wall, her group met every Thursday afternoon from one to two. It was hardly a coincidence that everyone was here; she meant for me to crash her little party.

I was the guest of honour all over again.

I wanted to explode. I didn’t come for show and tell. But Lynn Braidwood had information I needed, and my mother’s phone number besides. Anything I said would make it back home before I did. I had no choice but to put up a good performance.

I’m fine with that, I told her, smiling, lying through my teeth, and I know we go way back, but please, try to call me Harrison.

She nodded, stepping aside, as the 12 disciples rose to meet me, wide-eyed, overeager, and the questions started coming, fast and furious. Are you happy? Do you feel loved? Do you feel like your birth mother made the right decision? Do you feel like we made the right decision to adopt? What’s it like being Black with white parents? They crowded me, awaiting my response, desperate to be told that all is well within my soul.

It wasn’t, though — especially surrounded by these women. I saw at once their need to solve their children, to decode them. I saw that not one knew how to bridge the gap of race that kept them from connecting with their kids, that had them flailing at a stranger, seeking clues and validation. They couldn’t see beyond the skin; they couldn’t make it cease to matter; they couldn’t close the ever-growing distance it created. Neither could they shake the sense that, somewhere, they’d gone wrong — that something seemed to undercut the love they claimed to have for their adopted sons and daughters.

It was clear that these people were completely ill-equipped to raise Black babies. They seemed to think that I could fix it for them. I was reminded of that movie, The Truman Show, where the actor Jim Carrey discovers that his world has been constructed to entrap him, to exploit him in his ignorance, and that his reality is false, and designed, above all else, to keep him from seeing himself as a product, consumed by the masses without his consent.

I was so upset, I nearly spoke my mind.

What the Hell are you doing here? I almost said. Why lean on me when you could ask your own children? What stands in your way? What are you afraid to talk about? If Blackness so confounds you, just admit it. Let them know that you are lost. You think you can continue to avoid a touchy subject? You think your child believes that you are colour blind? Oh please. Your silence shouts the truth and drowns you out. The world is already teaching us all sorts of things about race and racism. If you haven’t learned the language, you are losing, you have failed.

You enshrine our inferiority. Even now, your feelings take priority over mine. You allow us to be mocked. We wake up every morning and the sky itself is looking down, disgusted. We look up to you; you look down at your feet. Don’t look down, you cowards, look closer, come closer. Tell me I am worthy of love every day, or in your silence, you have said: you are unworthy. You leave me to be beaten senseless by a world that hates me, and you raise me as though I should hate myself too. It is a vile way to treat a child you were given.

But I could never say these things to my own mother, let alone 12 of her. I wanted every one of them to like me. I knew that it would happen if I sought to reassure them.

Of course I’m happy, I began, and more than that, I’m grateful — for the opportunities I’ve been given, for being rescued from darkness and placed on the path that God has prepared for me. I received nothing but love from my adopted family, and all the advantages they could afford. My education has been paid in full. I start graduate school in the fall. I’m the boy who made good. Look at me go: diploma in hand, a bright future ahead. The world is my oyster. I’m thriving.

I saw their eyes brighten. Relief washed over the whole group. One by one, they praised me for my eloquence and thanked me for my willingness to speak so candidly. They all left with smiles on their faces, and again I felt like a clown — a classier clown, mind you, like a standup comedian or something. I stood by the sofa, ashamed, as the room emptied out.

Satisfied, Lynn Braidwood led me into her office.

Now there are two ways we can do this, she said. There’s the hard way, where you go through the government and submit some paperwork, and that paperwork is sent to your birth parents, and then it’s sent to me, the intermediary, to give to you, and we go back and forth for months or years until everything is hunky-dory. It takes forever.

Oh, I said.

Or we can do it the easy way: I give you their names, and you can probably find them on Facebook.

Let’s do that, I said.

Excellent, Lynn Braidwood said. Then you can have this now.

She handed me a document. BIRTH FAMILY HISTORY, it said, underlined. Scanning the sheet, I stopped at the second subheading — Racial and Ethnic Origins.

Mother was born in Ghana, Africa and is of Negroid racial background and Afrikkan nationality. The birth father is a Caucasian whose parents were born in the Ukraine and are of German national origin.

Maybe I’ll read this later, I said. Their names aren’t on it anywhere, and that’s really all I’m after today.

Right, she said. Your birth father’s name is Cory Klein. He lives in Langley. And your birth mother, Tee, lives in Seattle, last I checked. She bounces around, though. I never quite know where she is.

What’s her full name?

Hold on, it’s a real mouthful, Lynn Braidwood said, rifling through her papers. Ah, here we go. Her name is Trinika Arthur-Asamoah.

My heart sank. It was the Blackest name I’d ever heard. Again, I wished I hadn’t come. I thought of Prophet K; I thought of Courage; I thought of the girl that I saw, sometimes, at Trinity. I hid from these people, consumed by self-hatred, afraid they would see my discomfort with Blackness. How could I let my own birth mother see it? How could I account for the limits of my language, or my lack of experience with life outside of whiteness? She would be dismayed to find I was not much of a Black man at all.

I logged on to Facebook that night, and I searched for my birth mother, hoping to hit a dead end. I entered two letters — the T and the R — and the rest filled in for me. The internet already knew there was something between us.

I sent her a friend request and a short message:

Hi Trinika, it’s Harrison. By all accounts, I’m your son! It’s taken me a long time to get to the point where I’m ready to meet you, but I think I’m there now, so here I am. At your earliest convenience, I’d love to reconnect and go from there.

Three days passed before my request was accepted. I checked for a new message and saw the chat bubble beside Trinika’s name. She was writing something. I waited, but the icon disappeared, and I was relieved to have to wait a little longer. Why rush?

I clicked around, scanning my birth mother’s Friends list, and that’s when I located Cory. That was easy. ADD FRIEND.

I copied and pasted the very same message.

He messaged me back right away.

I am very happy that you finally made contact with me.

You are right. You are my son. And although we have never met, we have never stopped thinking about you, and how life is for you. I know that you may have a lot of questions, which I would be happy to answer, but know this: You were given up for adoption purely out of love and, to date, it is the hardest thing I ever did. I think that when you hear the circumstances you will understand.

In my youthful careless days, when I decided to ink up my back, your name was the first thing that was permanently placed on my body. You since changed your name. Thanks for that. Now I need to have another baby and name him Jordan, just so the tattoo has some significance. (Joke.)

Your brothers and sisters know all about you and have been patiently waiting for you to come see them. When people ask me how many kids I have, I will occasionally say four. Tarana, my seven-year-old, is always there to correct me by saying: You forgot Jordan again, Dad. You have five kids.

We would love to have you over for a bbq anytime. We are available as early as tomorrow night.

Wait, I thought, did he just call me Jordan?

I reread the message. My birth father used the name twice. But it wasn’t my name. Jordan is the guy I used to work with at the House of James. My name, I seethed, in my rearranged bedroom, is Harrison.

The following night, at his house, I tried to tell him.

Excerpt from 'Invisible Boy: A Memoir of Self-Discovery' by Harrison Mooney. © 2022. Published in Canada by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved. ![]()

Read more: Books, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: