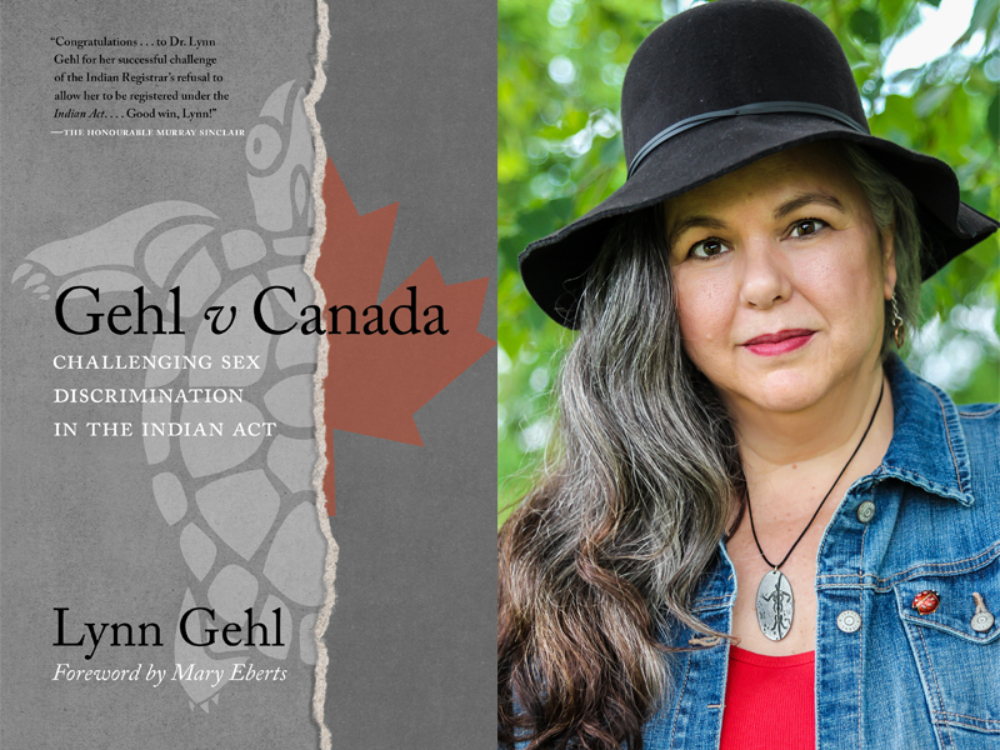

[Editor’s note: In 2017, Lynn Gehl, who is Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe, won an important case at the federal Court of Appeal about gender and Indian status. The ruling in the case determined that Gehl could in fact be registered under the Indian Act. The following excerpt from ‘Gehl v Canada’ documents an earlier period of Gehl’s years-long battle, in which she tells the story of her fight, the barriers she faces, and the ways in which patriarchal colonial culture attempted to separate generations of women in her family from their rightful cultural identities and heritage. ‘Gehl v Canada,’ now out with the University of Regina Press, offers an insider’s analysis of the many ways in which the Indian Act and the courts have disenfranchised Indigenous peoples, in particular, Indigenous women. This essay has been condensed; the full essay can be read in Gehl’s groundbreaking book, ‘Gehl v Canada.’ For more information about Gehl and her work, visit her website.]

How would you answer the question “What is your cultural identity?”

There are many people living in Canada today who struggle with issues of identity in terms of their culture, ethnicity, minority status, sexuality and race. Many people have relocated to Canada against their will, while others, for many reasons, made a conscious choice. These dislocated and relocated people at some point in their lives, if not all their lives, will wrestle with their identity and their sense of belonging. However, for many Aboriginal women and their children this is not a question of belonging and being but rather a question of law. The oppression of Aboriginal women and their descendants is of a particular nature as their cultural identities are entangled with legislation.

In Canada, the federal Indian Act determines who is and who is not an Indian. Legislation titled the Indian Act was first formalized in 1876. It was early in 1869 when “patrilineage was imposed” on Aboriginal peoples and “Indianness” was defined as applying to any person whose “father or husband was a registered Indian.” Eventually, in 1951, the Indian Act underwent one of its infamous amendments, known as section 12(1)b. Here the Indian Act dictated that Indian women who married non-Status men were no longer Indian. The goal of the Indian Act was one of assimilation and of civilizing the so-called savages — a national agenda. Ironically, what this type of policy did was subjugate women to the status of “chattel of their husbands.” It stripped women of their rights socially, politically and economically and made them dependent people. By European standards, this was the proper location for women on the social evolutionary scale.

The struggle to have the gender inequalities removed from the Indian Act, which continues today, has been a difficult process. The paternalism is so well entrenched in Aboriginal communities that women have been struggling internally as well as externally to have their rights acknowledged. The oppressed have often proven to be the oppressor.

One of the first women to speak out publicly about section 12(1)b was Mary Two-Axe Earley in the 1960s. Legally, the first women to argue against the sex discrimination set out in 12(1)b were Jeannette Corbiere Lavell and Yvonne Bédard. In 1973 the Supreme Court of Canada determined that the Indian Act was exempt from the Canadian Bill of Rights. Part of the problem in the fight to remove the discrimination was the lack of unity and support the women had from the National Indian Brotherhood (now called the Assembly of First Nations). The NIB feared changes to the Indian Act would jeopardize the federal government’s legal responsibility to Status Indians. In 1977 Sandra Lovelace Nicholas took her complaint against 12(1)b to the UN Human Rights Committee, where in 1981 she was not successful. In 1979, the Tobique Women’s Group of New Brunswick organized a grassroots march from Oka, Quebec, to Parliament Hill in Ottawa, the country’s capital, to raise awareness of Aboriginal human rights specific to Indian women.

In 1985 the Indian Act was amended to conform to the equality provisions of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. [... But] much of the sex discrimination still exists in the act.

I, my family, and many other First Nations people continue to be excluded from registration as Indians. Aboriginal peoples who wish to pursue registration as Status Indians with the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development must have extensive knowledge of their family history and great determination, as well as awareness of the continued discrimination against women and their descendants perpetuated by section 6 of the current Indian Act.

[...]

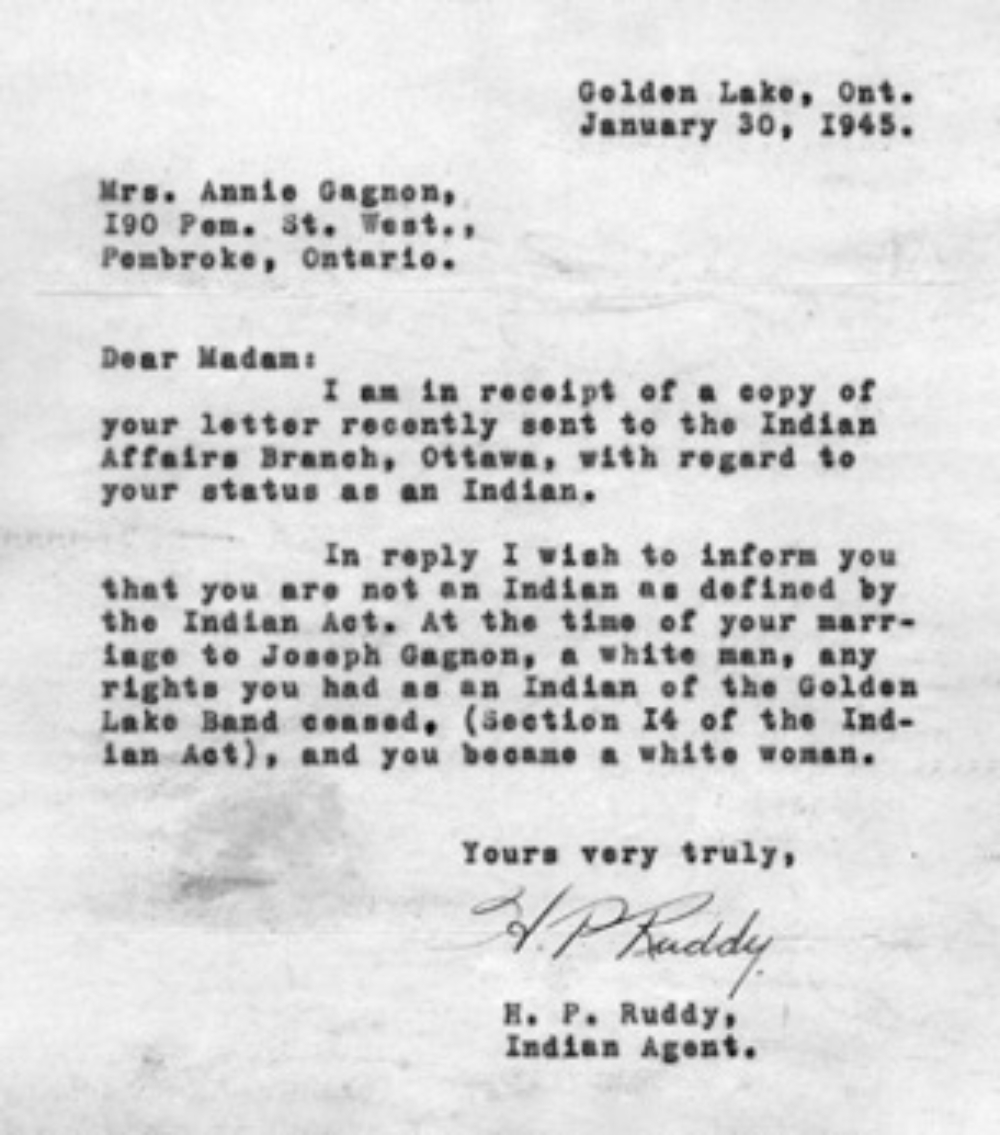

On Jan. 2, 1945, my great-grandmother wrote a letter to Ottawa. She explained that she was having some difficulty with her nationality and was wondering if the government could help in any way. “I would like to know if I am counted as an Indian. Please let me know soon.” Four weeks later, she received a reply.

Prior to the implementation of Bill C-31, the Indian Act discriminated against Indian women by revoking an Indian woman’s status upon her marriage to a non-Indian man. However, an Indian man was allowed to retain his status and pass it to his non-Native wife. This inequity prevented Indian women from passing Indian status on to their children (in their own right), while permitting Indian men to do so. This is how my great-grandmother lost her status, and as a result, so did my kokomis. Of particular interest is that my great-grandmother’s husband was also a Native person through his mother (my great-great-grandmother [Angeline]), [but] not his father. [... B]ecause of the male lineage criteria he too was deemed a “white” person.

My kokomis, Viola, was born and raised on the reserve. In 1927, at the age of 16, she and her parents were escorted off the reservation of Golden Lake by the RCMP. They lost their home along with most of its contents and, from what my kokomis tells me, they were given nothing to start their new lives as “free” people.

[...]

[... W]hen my father was born Viola recorded her racial origin as French despite the fact that both of her parents, Annie and Joseph, were Native. [...] I was told that [she] gave birth to my father where she was born, on the reserve of Golden Lake, where she felt most at home. He was born of unknown paternity. The midwife who attended my kokomis was my father’s great-aunt Maggie, and she is who he spent his early years with. His life on the reserve came to an end, just as his mother’s had before him, when his Aunt Maggie was also escorted off by the RCMP.

When one considers the legacy of the oppressive legislation, the effects of residential schools, and poverty, it should not be difficult to understand the deleterious effects on Indian women and their children materially, culturally and psychologically. These effects leave people lacking confidence and self-esteem, making them vulnerable to illiteracy, hostility, alcohol and suicide. For example, in 1992 Health and Welfare Canada reported that the suicide rate among registered Indians was at least three times the Canadian average. This reality is a scenario all too familiar for Native peoples. For me, this also proved to be the legacy of the Indian Act. My father died suddenly in 1988. I know that it was the direct result of the oppressive nature of the Indian Act and the forced assimilation process. A few years later, I proved his eligibility for registration; however, I was too late. I am sure he would have given his other little finger to have his identity affirmed through Indian status registration.

When Bill C-31 came into effect, I was aware that its major changes involved reinstating women previously enfranchised because of whom they had married. My kokomis, Viola, and her mother, Annie, would regain their status. I was also aware that Annie’s husband, Joseph, was entitled through his mother, Angeline. This was where the challenge presented itself. In order for me to have my father entitled, I had to prove that both of his grandparents were entitled. That is, I had to prove that both Annie and Joseph were entitled to be registered with Indian Affairs so that status could be passed to my kokomis, Viola, in such a manner that she, in her own right, could pass it to my father; otherwise, he would be affected by what is known as the second-generation cut-off rule, which results in the loss of Indian status after two successive generations of parenting by non-Indians as defined by the Indian Act.

I started by spending many hours with my kokomis learning my family history via the Oral Tradition. Without this opportunity I would not have been successful, and for this I am eternally grateful. It was difficult, though, because she was very bitter and often sad about her life on the reserve. She remembered our family history well. She told me about her mother, Annie, and her father, Joseph. I was most interested in finding more information about Joseph’s mother, Angeline. My kokomis did not know much about Angeline, although she did repeatedly say that “Angeline was a Black Indian from the Lake of Two Mountains who adopted two French boys whose mothers were unwed.”

After the family history lesson, I constructed a family tree and began the formidable task of searching for the documents to prove my ancestral link to a past Band member. This proof is required to fulfill the Indian Affairs registrar’s demand that “the applicant connect the ancestor to an existing band as the basis of his [sic] entitlement regardless of the date of evidence.”

I sent away to the Office of the Registrar General for birth certificates of my father, my kokomis, and myself. I also sent away for the marriage certificate of Annie and Joseph as well as the death certificate of Angeline. As discussed previously, the registrar general holds the records of deaths, marriages and births for 70 years, 80 years, and 95 years, respectively, after which time the records are microfilmed and then held at the Archives of Ontario.

When I first entered the archives library, I was overwhelmed — not surprising when one considers that I am visually impaired. The library essentially consists of numerous filing cabinets stuffed with microfilm. Archivists on staff can assist in your research, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Needless to say, I was discouraged, especially when I read an outline that was prepared by the archives to explain various Aboriginal sources. It explained the difficulty with Native surnames and how they vary widely in records written by people who did not speak the Native languages. An additional blow was an Archives of Ontario cautionary note that read, “Aboriginal ancestors more than three generations away from you may be hard to document and therefore very difficult to claim status from.” I had an enormous task ahead of me with having to research back five or possibly six generations to Angeline’s male family members.

[...]

When I would find birth, marriage, death or census records that I felt might have significance, I would photocopy them; I would then take them home and construct and reconstruct my extended family tree in an attempt to look for clues as to where I could find Angeline’s male family members. It became such a difficult task that occasionally I would stop for weeks or even months at a time.

At one point I had stopped for a period of several months when I once again began to act on my desire to be a registered Indian. This turned out to be the day that I found what I needed. It appeared that Angeline was at the home of the birth of her brother’s child. The date of the birth was Aug. 20, 1882. For unknown reasons, the child’s birth registration was delayed until Dec. 1934, 52 years later. It seems his mother was missing and, since Angeline was present at the time of his birth, she was the only person qualified to sign the declaration. This declaration of delayed birth stated her brother’s name as the father and herself as the child’s aunt. This document was the patrilineal link that tied the two surnames together — Angeline’s married name and her brother’s — which could connect her to a Band member. I knew that what I held in my hand was the necessary document, and I quickly sent all the documents and required affidavits along with several applications to Indian Affairs.

By this time I was familiar with section 6 of the Indian Act. I was certain my great-grandmother, my great-grandfather, my kokomis, and my father would all be reinstated or registered. I was uncertain about myself because I did not know how my father’s unknown paternity would be interpreted.

[...]

Indian Affairs applied section 6 to my family in the following manner: Angeline was reinstated as 6(1) status; her son, Annie’s husband, was registered as 6(2) status. Annie was reinstated as 6(1). My kokomis [Viola], the child of a 6(1) parent and a 6(2) parent, was registered as a 6(1). My father’s combination of parents was applied as 6(1) plus [non-Status] and registered as a 6(2). The registrar, when applying section 6, assumed a negative presumption for my father’s unknown paternity as being a non-Status or non-Indian person. This means that he cannot confer status to me in his own right, because a 6(2) plus NS (my mother is a non-Status person) equals NS.

All previous registered Indians in the Indian Register as of April 16, 1985, were granted 6(1) entitlement. This was also the situation when reinstating women who had lost status through marriage; “however, their children are entitled to registration only under section 6(2)” of the Indian Act. “In contrast, the children of Indian men who married non-Indian women, whose registration before 1985 was continued under section 6(1), are able to pass on status if they marry non-Indians.”

Alternatively stated, the new rules of section 6 were being applied retroactively to Indian women and their children, creating an inequity, because 6(1) registration permits a person to pass on status to their children in their own right, yet 6(2) does not.

[...]

I was denied registration [on Feb. 13, 1995]. With this denial it became evident to me that if my female ancestors had been male, I would be entitled to Indian status today. Had they been male, they would never have lost status registration and they could then pass it to me. Since all previous entitlement continues, I would be a 6(1) in my own right and I could therefore pass status on to my children. In this way the present-day Indian Act continues with the theme of discrimination on the basis of sex. Furthermore, the Indian Act continues to violate section 15 of the charter. Section 15(1) provides that all individuals are equal before and under the law.

[...]

I submitted a letter of protest on March 16, 1995, and on Feb. 4, 1997, I received a letter from the registrar concluding that my name had correctly been omitted from the Indian Register. I filed an appeal claiming discrimination on the basis of sex and marital status. Indian Affairs denied my appeal in April 1998.

I am now content with my identity, partly because of my new understanding of these huge issues and partly because I realized, during the process, that legislation cannot tell me who I am. It is as a matter of principle that I continue to appeal to the appropriate court as outlined in section 14.3 of the Indian Act.

In conclusion, I would like to suggest a very simple, fair, logical, and equitable remedy to eliminate the continuum of discrimination within the Indian Act. All children, and their descendants, born prior to 1985 to an Indian man or an Indian woman regardless of who they married should be entitled to registration under 6(1). The new rules of entitlement should then, and only then, be applied to all births equally after 1985. This would resolve the continued inequities in the current Indian Act between men and women and would then bring it into accord with the charter. This would also resolve the issue of unknown paternity before 1985, as unknown paternity is also being interpreted in an unequal manner.

The biggest challenge in having my family members reinstated or registered was the registrar’s demand that I connect my ancestors to an existing Band member as the basis of my family’s entitlement. I found two official documents in which Angeline was recognized and recorded as an Indian: her death certificate and her marriage certificate. This was not enough. I had to further my search until I could prove a link. This is grossly unfair and an unreasonable request when one considers that “there are countless historical records of Indians who never belonged to a band.” Angeline was an Indian, regardless.

[Proving] Aboriginal ancestry, in particular, being able to prove a link to an existing Band member, is [also] an enormous task. Individuals require time, money, stamina and great determination to fulfill the registrar’s requirements. Many [Indigenous] peoples are poor or unemployed as a result of the forced assimilation process. When the Indian Act was amended, assistance in the form of guidance from genealogical researchers should have been made available to the non-Status communities to help them in their quest for their identity as well as registration.

Finally, Sharon Donna McIvor argues that the Indian Act, with its paternalism and colonial ideologies, has created a “fictitious body” of Indians. What McIvor implies by this is that the Indian Act is a legal construction based on Eurocentric notions of what defines an Indian, excluding many Aboriginal Peoples from that definition in the process.

I will never see myself as a Canadian first, but rather as a First Nations person. My ideas of who I am and who my ancestors were will always extend beyond national policies and boundaries of control and assimilation. Neither identity nor human behaviour can be constructed through rigid definitions such as the Indian Act. My identity as an Aboriginal person was partially achieved through political struggle and the need to realize the potential of my genetic memory. I feel this way despite the fact that I am not a legal Indian.

Excerpted from ‘Gehl v Canada: Challenging Sex Discrimination in the Indian Act’ by Lynn Gehl. Copyright 2021 Lynn Gehl. Published by University of Regina Press. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: