[Editor’s note: This year marks Trina Moyles’s sixth season as a boreal lookout in northwestern Alberta. It is “by far,” she tells The Tyee, “one of the most intense fire seasons I’ve experienced.” Parts of northern Alberta have been parched by drought since mid-May, and June rains were lighter than normal. Most lookouts, Moyles says, have spent a record number of days on “high and extreme” hazard. Which means long shifts in their towers scanning the horizon. “It’s been an exhausting season,” Moyles writes. “Imagine spending 11 hours in a small Plexiglas dome 100 feet up in the air in 40-degree heat — day after day and staying vigilant for wildfires.” Some colleagues with two decades of seasons under their belts say they’ve never seen one like this. “I’ve been grateful for a supportive community of lookouts, firefighters, radio dispatchers and pilots,” Moyles adds. “Anyone who's worked in wildfire knows there’s a strong sense of community. We look out for one another, no matter how distant our towers may be, working together to endure a difficult fire season."]

In early April 2016, I drove to the Hinton Training Centre, a government facility, to attend an eight-day mandatory lookout observer training course. The campus consisted of an administration building and two residential buildings including dorms, a mess hall and a recreation room. There was a building with five flights of stairs for firefighters to launch themselves off and rappel down and a 40-foot practice fire tower nearby.

In the student residence, the military-style dorm rooms held two single beds, two drawers, two desks and two lamps. I’d be bunking with a detection aid, a tower support person from the High Level district. Lining the hallway walls were a series of black-and-white photographs of forestry personnel taken over the last century: rangers, foresters, firefighters, pilots and lookouts. One of the photographs, dating back to the 1950s, portrayed a group of lookouts gathered around a large compass device, the Osborne Fire Finder, which was used to locate the bearings on the smoke from wildfires.

I looked into the faces of these men and wondered: Where were all the women? Later, I’d learn that the first female lookout wasn’t hired until the early 1970s; apparently, she’d applied for the position using a man’s name. Much had changed in forestry over the past 50 years, however, with more women stepping into roles that had been traditionally held by men: rangers, firefighters, helicopter pilots, air-attack officers and so on. Recently, I was surprised to learn, more than half of Alberta’s lookouts were women.

The following morning, the cafeteria was crawling with firefighters: young, athletic men and women — although mostly men — dressed in the standard mustard-yellow-and-green Alberta government uniform. The rangers, men and women in their late 30s and 40s, wore sand-coloured shirts and slurped coffee at their own tables. The radio dispatchers sat at a table by the window — all women, I noticed, who appeared to be in their early to mid-20s, and who looked, on the surface, a lot like me. I began to wonder if I had applied for the right job. Maybe I’d be better suited for a summer working the radios. At another table sat the dozer bosses, who were responsible for clearing the bush down to mineral soil to prevent the spread of larger, more volatile wildfires. They had a harder look to them, with grizzled cheeks and paunchy bellies. They wore blue jeans and truckers’ hats and loitered around the entrances sucking on cigarettes. I figured that the attendees dressed in plain clothes, who didn’t look as though they belonged to any particular group, must be here for the training to become lookout observers.

There were only a handful of us. We were a motley mix of candidates, about a 50-50 split between men and women, and a wide range of ages, from mid-20s to mid-60s, including a couple of forestry students, a musician, another writer, a biologist, a photographer, a retired teacher and a former trapper. We were a pack of quirky, introverted nature enthusiasts, each of us thrilled to have landed one of the few openings. Of the 127 fire towers in the province, only 10 had required new lookouts for the 2016 season, which, I’d learn, wasn’t at all uncommon. The majority of lookouts tended to migrate back, summer after summer, to their towers. Many were what they called “lifers,” operating on a seasonal lifestyle, building second lives and homes at the towers.

“It takes at least five years to make a good lookout,” one of the managers told us on the first day of training. “What we teach you here this week, you’ll have to apply at your own tower.”

No two towers were exactly the same, he said. There were towers situated atop mountains, like Jack Kerouac’s refuge on Mount Desolation, a single-room structure in which the lookout both lived and worked, looking out the windows for smoke. Other alpine lookouts were two-storey structures with a cabin on the main floor and a ladder or stairs that led up to the cupola. There were 40-foot towers, 60-foot towers, 80-foot towers and 100-foot towers — and even a few rare 120-foot towers. There were towers in the foothills, overlooking the southern wild grasslands; towers surrounded by deciduous forest; towers that peered into the fields of farmers and ranchers, and ones hunkered down next to oil well sites and gas plants. There were towers next door to military aerial operations, and ones you could reach only by helicopter. Towers that would only ever see fires caused by lightning, and settlement towers, which rubbed up against the edges of communities where humans usually caused fires. Some towers were so far north that they sat on the Canadian Shield. The farther north you travelled, the more the black spruce shrank down to stubble.

I would be going to one of the last true “wilderness” towers, inaccessible by road, a tower overlooking an expanse of forest.

Over the next week, we sat through lectures on weather, fire behaviour and occupational health and safety. We studied photographs of smokes and false smokes — phenomena such as road dust and pollen clouds that look deceptively like smoke.

The trainer flipped through slides. “Smoke, or false smoke?” he asked.

My eye zeroed in on the column of black smoke rising from the stand of pine and spruce. “Smoke,” I said confidently.

“Look again,” he said, and I immediately noticed the black cylinder beneath the smoke column. An industrial flare stack.

There were a thousand ways to be fooled from the fire tower, particularly from 40 kilometres away. Even a tuft of cumulus cloud, rising behind a distant ridge, could look like a puff of white smoke. Sunlight falling on a distant cutline, or a stand of white birch or aspen. Fog draping over the sharp teeth of the spruce, or columns of moisture rising after a violent storm. A ribbon of black diesel coughing out of the exhaust pipe of an old tractor and staining the sky.

“It’s not necessarily about just looking and seeing out there,” said one of the managers. “It’s more about knowing where, when, and how to see.”

Before training began, I wondered if the government trainers would bring up the disappearance of Stephanie Stewart, now a decade-old unsolved mystery. I was curious if my fellow trainees were even aware that a lookout had gone missing, that she’d never been found. The story lingered in the back of my mind. It was a reminder of a risk, a reality: I was signing myself up to live alone in the woods. I would be vulnerable.

“One of our lookouts was murdered in 2006,” the head manager said solemnly on day one.

My eyes widened. I felt my colleagues stiffen and suck in their breaths. That word — murder. My body felt cold, the kind of damp cold that sinks into your bones. The RCMP had recently reclassified Stephanie’s case from “missing” to “homicide.” There had initially been rumours of a bear attack, or speculation that she’d wandered alone into the woods, but they’d quickly ruled out those possibilities. Very little information had been published in the media after the disappearance, but apparently the RCMP had enough evidence to be certain of foul play. I respected the trainers for addressing the event directly, though it only fuelled the fear I already felt. The memory of my own trauma reverberated in my body. I wondered whether symptoms of my latent PTSD would emerge at the tower.

On the third day, we practised locating and mapping wildfires using the Osborne Fire Finder, the same device that the group of lookouts had gathered around in the photograph dating back to the 1950s. The fire finder was a large, heavy compass etched with bearings from 0 to 359 and set up facing true north. A rifle scope, a telescopic sight, was attached to it. When it was my turn, I swung it around, focusing on the mock smoke through the crosshairs, and then looked down to record the corresponding compass bearing — 56 degrees and 10 minutes. The mock fire was 10 kilometres away.

I then rushed over to the cross-shot map, a map with a network of large circles indicating fire towers, and pulled a piece of string from the centre of the map — the location of my fire tower — along the compass bearing to a distance of 10 kilometres. The next step was to call my hypothetical tower neighbour. “What’s your bearing on the smoke?” I asked through the hand-held radio device. “Two two-five degrees,” came the response. On the map, using a second piece of string from the neighbouring fire tower, I triangulated our bearings and pinpointed an exact location. There. X marks the spot.

It’s a fact that a compass, a map, pushpins and two pieces of string have been the trusty tools used to detect wildfires for over a century in Alberta. Of course, there are other methods: helicopter patrols, fixed-wing aircraft patrols, 310 calls from citizens who spot fires along roads and highways and train tracks. But nothing can replace a set of seasoned eyes able to differentiate between a real smoke and a false one. The most experienced lookouts in the province can estimate the location of a wildfire — sometimes burning 50, even 60 kilometres away — within hundreds of metres from where it burns. It’s not a matter of seeing so much as knowing the forest and features around the 40-kilometre radius that was each lookout’s responsibility.

We’d have to know every road, every cutline through the bush, every set of rail tracks, every farmhouse, every lake, every ridgeline. Some of these features we’d be able to see from the tower with the naked eye, or through binoculars, but others would be blind to us, hidden behind hills and dense forest.

“You’ll learn to keep extra vigilant on long weekends for campfires,” they told us. “And on windy days, watch for permits jumping into the bush.” This last bit referred to a farmer’s brush pile fire accidentally blowing into the forest.

There were dozens of scientific names for clouds that would help us understand the weather and risk for fire hazard in the forest. Cirrostratus, altostratus, altocumulus, cumulonimbus — I couldn’t keep track of them all. The cumulonimbus, or thunderhead, was one to stay alert for. A ranger flipped through photographs showing the progression of thunderstorm development, the first image showing a mere whisper of cloud. The barely visible cloud grew steadily into a dark tower, its head becoming a monstrous, angry, mutant cauliflower. These were the kinds of clouds that would shoot lightning strikes capable of starting fires.

Lightning caused fewer than 50 per cent of the wildfires in Alberta, but where these fires ignited, I learned, they burned the largest areas of forest in the province. The tower I would be going to — in less than a month — was considered a lightning tower because the surrounding area was mostly uninhabited by people. Fires in my territory were much more likely to be caused by natural phenomena than by humans.

“Don’t climb your tower if there’s a storm cell within 12 kilometres,” said one of the rangers. They assured us that the towers had lightning grounding systems, underground systems to absorb the shock of a strike, but only if we were tucked safely in our cupolas, or cabins. Recently in the United States a woman had died when lightning struck her tower while she was climbing the steel ladder.

Over the course of the training, the instructors grilled many don’ts into us.

Don’t climb the tower if there’s more than 90-kilometre-per-hour winds.

Don’t expect your food to show up exactly when scheduled.

Don’t leave your garbage outside, because it could attract bears.

Don’t drink unfiltered rainwater without boiling it.

Don’t say anyone’s name over the radio, for security reasons.

Don’t go for a walk without your radio and bear spray, and without telling a neighbour of your whereabouts.

Don’t expect minor issues to be resolved at the drop of a hat.

And whatever you do, do not go out there to find yourself.

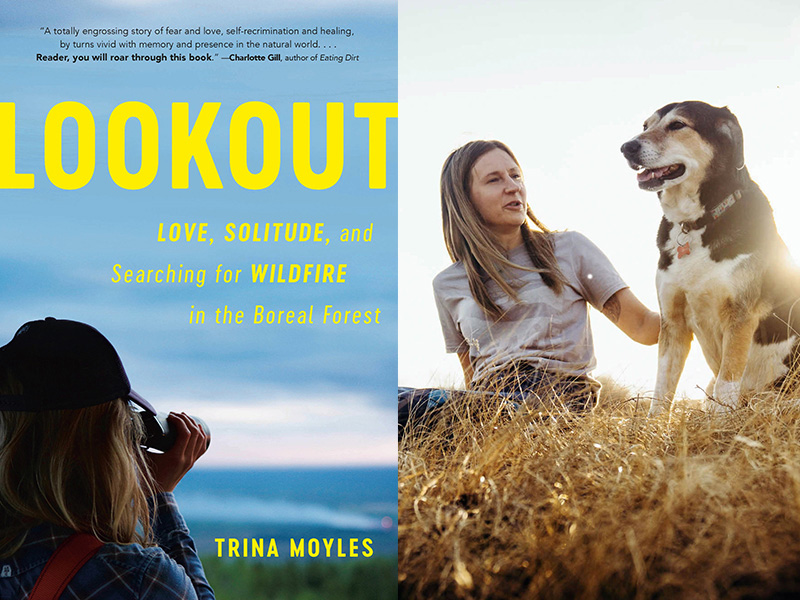

Excerpted from 'Lookout: Love, Solitude and Searching for Wildfire in the Boreal Forest' by Trina Moyles. Copyright © 2021 Trina Moyles. Published by Random House Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: