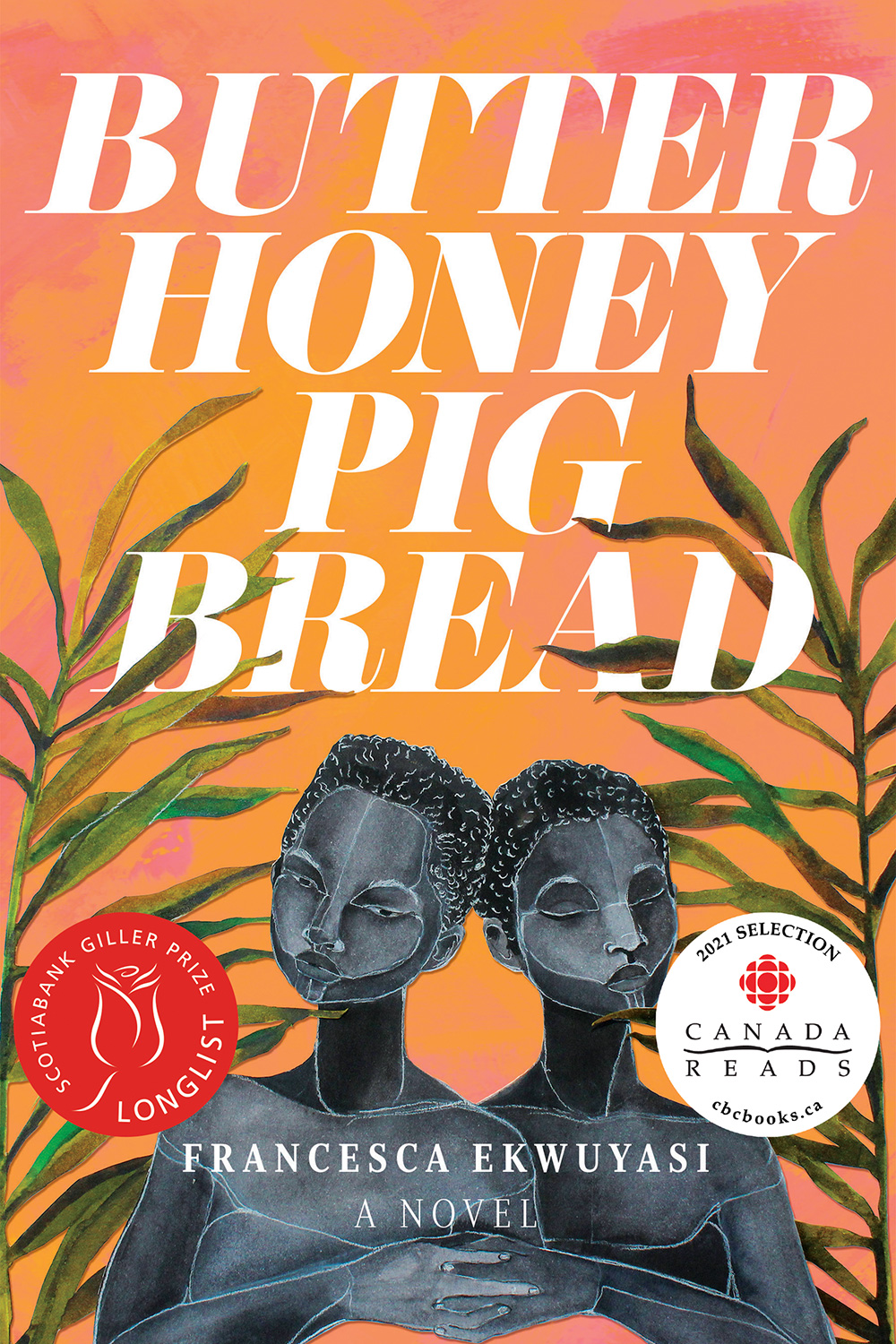

Francesca Ekwuyasi’s Butter Honey Pig Bread is the story of a fractured family: twins Taiye and Kehinde, who grew distant after a traumatic incident, and their troubled, dreamy mother Kambirinachi. Taiye, a queer chef living in Halifax, distracts herself with sex and partying to avoid confronting her guilt over the “bad thing” that happened to her sister. Kehinde, in Montreal, blossoms as an artist, falls in love and marries. After years of separation, both sisters return home to Lagos, reunited with their mother.

Ekwuyasi has a lot in common with her characters: like Kehinde, she is an artist and an avid reader; like Taiye, she’s queer and very into delicious food. And the sisters’ journey resembles her own. She grew up in Lagos before leaving for university in upstate New York.

“It was horrible at first,” she said, “because I arrived in January, and I didn’t understand layering as a way to keep warm, so I just wore regular clothes and a big coat.”

Since then, she’s figured out how to dress for severe winters. It’s necessary for her life in Halifax, a city which she renders in loving and precise detail in Butter Honey Pig Bread.

Butter Honey Pig Bread was published by Arsenal Pulp Press in September 2020. It’s shortlisted for Canada Reads 2021, championed by chef and author Roger Mooking.

“It took me a long time to write, and as a result there are a lot of genuine elements of my personality in that book,” Ekwuyasi said, explaining how her love of food made it onto the pages. “I loved [watching] Nigella Lawson. That’s actually how I knew I was gay — I was like, ‘Oh, I guess I really love flan!’ but what I actually loved was Nigella talking to the flan like it’s her lover.”

Beyond sexy desserts, Ekwuyasi’s bookshelves and her novel have even more in common. In this recent interview, Ekwuyasi talks about twins, trauma and why she believes queer smut is legit lit.

You grew up in Lagos — are there books that reflect your experience of the city?

A book I read when I was 15, called Everything Good Will Come, by Sefi Atta. It’s a coming-of-age novel, so it starts in the past, the time my parents and aunties knew, and then moved into my present. It was set on Lagos Island, where I lived, so as a teenager I felt like, “I know this!”

Also Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus and Americanah showed a life in Lagos that I was familiar with in some ways. Especially Americanah, which showed that intense desire that so many Nigerians have to leave and go to America, the land of promise. It really showed this thing I knew deeply in my own body, from my family, who had that same desire to escape.

Another book about Lagos that I just read, early last year during the first part of lockdown, was My Sister the Serial Killer, by Oyinkan Braithwaite. I listened to it as an audiobook, and the descriptions of Lagos — the heat, the traffic, the police, the terrible customer service — they felt so true to my experience.

How would you describe your literary tastes?

It’s become very apparent to me during the pandemic that the feeling I want to have after I’ve read a book is that I miss it. I want books that are really sensual, that immerse me in their world. I love books that I can really relish.

There are two recently that I felt that way — one was Less, by Andrew Sean Greer. That book was so cinematic, and I really felt the main character’s emotional landscape.

The other was Next Year, for Sure, by Zoey Leigh Peterson. It’s really good. I didn’t think it was for me at first, but then I felt really grounded in the place of the book. And one of the characters, I felt like I really got her — the other character I hated! I like books like that, which are slow and immersive, and not necessarily plot-driven.

How do you choose your books?

It’s tricky, because often I’ll just go by an author — if I like them and know them, I’ll pick up their next book. But some of my favourite authors have written very different types of books, so that’s not always reliable. Like Zadie Smith — I read White Teeth at just the right age. But her collection of short stories, Grand Union, or NW, they’re not at all similar.

Most of the time, I open the first few pages of a book to read them, and if I’m not moved by those, I put it down. I’m currently reading The Thirty Names of Night, by Zeyn Joukhadar, which I picked up that way.

What are you reading now?

I’m reading a lot of books right now, because I can’t focus on any one. One is Devotion, by Mary Oliver, which is a collection of poetry. I’m also reading Bestiary, by K-Ming Chang, which is a very visceral book. And also Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, which I’ve been reading slowly because I don’t want it to end. He’s so soulful in his craft.

Who are the authors that influenced you as a writer?

The one that comes to mind is Chinua Achebe, who wrote Anthills of the Savannah. That was the first time I read a Nigerian author, a Nigerian book, that wasn’t folk tales. It felt so contemporary, even though it was set like 20 years ago — it made me realize that you could write about Nigerian people today.

Until then I was just reading about white people, like Harry Potter — which I loved — but they had no roots in my own culture, which was so rich. That’s when I realized I could write a book about my experience, of Nigerian people doing Nigerian things.

Your debut novel, Butter Honey Pig Bread, is about a fractured family that includes twin sisters. In another interview you mention a Goodreads comment that “Nigerians love to write about twins.” Do you have a favourite book about twins, or twin folklore?

Yes, I did see that comment on Goodreads, that Nigerians love to write about twins. And I was like, “That is so true!” The first one that comes to mind is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun. It’s not a huge central plot, but there are twin characters, and they are super entwined in their twinness.

Also Helen Oyeyemi — she’s a British writer, but she was born in Nigeria, and her novel White Is for Witching is about fraternal twins.

Are the names of the twins in your book, Taiye and Kehinde, related to their twinness?

Yes. Kehinde and Taiye mean “the first one to come, the second one to come.” Taiye is technically the second-born twin, but the Nigerian folklore is that the first twin to be born is younger. So when you meet someone named Kehinde, you know they’re a twin. A lot of Nigerian names are quite literal.

Butter Honey Pig Bread is also a story about the experience and impacts of trauma, as well as the process of healing. Is there a book that shaped how you think about the way we move through trauma and carry it with us?

One was [Adichie’s] Purple Hibiscus, which is very much about a family going through trauma. It doesn’t have a tidy ending, but it has a cathartic ending.

Also, Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Udala Trees is a story about trauma and acceptance. It’s about two girls who have lived through the Nigerian Civil War, losing their families and their agency, and discovering they’re queer in a deeply homophobic world.

Another book about young femme trauma is Everything Good Will Come, about a girl’s evolving understanding of a close friend’s rape and trauma. Nigeria’s culture around sexual assault still very much involves those questions of, “Well, what were you wearing?” and, “What did you do to cause this?” So the book is about a character unlearning that, and relearning what happened to her friend.

Split Tooth by Tanya Tagaq is another stunning, lyrical book about the mundane traumas of everyday life.

And finally, The God of Small Things, by Arundhati Roy is about capital-T Trauma. I love it, but to this day I’m still so disturbed by it.

Butter Honey Pig Bread is a very sexy book, so I have to ask — what are some sexy books you love?

In Helen Oyeyemi’s collection of short stories, What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, there is some sex that I like. There is one character who won’t have penetrative sex, but they make out all the time, and I liked that. In Gingerbread as well, there are some graphic depictions of sex, and then at the end there’s some queer sensuality that I appreciate very much.

Shut Up You’re Pretty by Téa Mutonji is sometimes unnerving but still sexy. I’m such a fan of that collection — she really did something new.

And Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties is so sexy! Her memoir too... she does erotic literature that is very critical and brilliant. I’m working to convince everyone that queer smut is literature.

What stories or books did you read as you were discovering your identity as a queer woman?

That’s a big question, because the Nigerianness of it is complicated. I don’t think any fiction did that for me. But in Helen Oyeyemi’s White Is for Witching, the girl twin has a Nigerian girlfriend, and I was so obsessed with her character. She isn’t in it a lot, but it helped me feel it was possible, reading her Black queer characters.

What is the book you give most often as a gift?

Probably it’s this very slim book of poetry by William Carlos Williams that I love. There was a time where the one poem about plums was so popular — you know, “I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox” — but there are actually quite a few poems about plums. There’s one called To a Poor Old Woman that starts with munching on a plum. He loved plums!

I also give Disintegrate/Dissociate by Arielle Twist. I love to give that book, it’s a poetry book too. It’s incredible, she’s incredible. And adrienne maree brown’s Pleasure Activism, which I gave to almost everyone I knew when it came out.

Oh, lastly — The Book of Delights, by Ross Gay. They’re little essays, and they’ll make you happy! He wrote one essay per day about things that gave him delight. They’re very real and beautiful.

What are you excited to read next?

I have two that I’m excited for. One is Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters. And The Man Who Ate Too Much, a biography of James Beard. I haven’t even cracked them open. I didn’t even do the thing of reading the first few pages to check that I’d like them. I just knew I was excited to read them. ![]()

Read more: Gender + Sexuality, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: