This month, New York City got an expensive lesson about why public transportation facilities should be publicly owned. It’s a wake-up for we who live in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland.

Waterfront Station, at the foot of Vancouver’s Granville and Seymour streets, is the flagship station for Metro Vancouver’s TransLink. The complex offers direct connections to Richmond, YVR, Surrey, the eastern and southern suburbs (via SkyTrain and West Coast Express), the North Shore (via ferry), Rapid and local buses, and adjacent cruise ships, helicopters, float planes, convention centres and hotels. It has nearly 13 million passenger boardings a year, about five million more than for users of the next busiest TransLink station. In the climate-warming decades to come, ridership will increase.

The historic 1914 building, built as the western terminus of the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway, serves as a lovely public entry and meeting hall.

Most people are surprised to learn that it’s owned by a private developer, Cadillac Fairview, which rents transit and office space to TransLink. The actual transit facilities are underground, or in a shabby shed attached to the building’s north side, a sad space much like New York City's tawdry underground Penn Station, detested by its daily 600,000 commuters.

But this month, New Yorkers got a huge improvement, the fabulous Moynihan Train Hall, built inside an elegant and gigantic former post office building across the street from the underground facility.

The new train hall cost US$1.6 billion, serves only half of Penn Station's train lines, and will cost another billion to restore all the service New Yorkers, commuters and visitors once enjoyed. But it has become a cultural sensation, and an instant destination. A New York Times headline gushed, “Moynihan Train Hall has achieved the near impossible; it has left New Yorkers feeling inspired."

Therein lies a cautionary tale, and a lesson for Vancouver, the Lower Mainland, and all three levels of government.

In the early 20th century when trains provided most suburban and intercity transportation, private railroads built stations sized and designed to the importance of the location. Penn Station, on the west side of Manhattan, was spectacular: a Beaux-Arts masterpiece designed by the august architectural firm McKim, Mead and White.

By the mid-1940s, it served more than 100 million passengers a year. But starting a decade later, air and interstate highway travel led to dramatic rail passenger declines. Looking to improve its bottom line, in 1962 the Pennsylvania Railroad sold the station’s air rights to a private developer to build the Madison Square Garden sports complex. In exchange, the railroad got a 25 per cent stake in Madison Square Garden, and a no-cost, smaller underground station in the basement, built on the cheap.

The demolition of the McKim, Mead and White building, and its sad replacement, caused an international uproar. “One entered the city like a god. One scuttles in now like a rat,” the architectural historian Vincent Scully famously wrote in the New York Times.

Public outrage catalyzed the architectural preservation movement in the U.S., new laws were passed to restrict such demolition, and landmark preservation was upheld by the courts in 1978, after the private Penn Central railroad tried to demolish New York’s other great railroad treasure, Grand Central Station.

Today, Penn Station serves more than 600,000 commuter rail and Amtrak passengers on an average weekday, and arrivals and departures have doubled since the 1970s.

Lessons for Vancouver

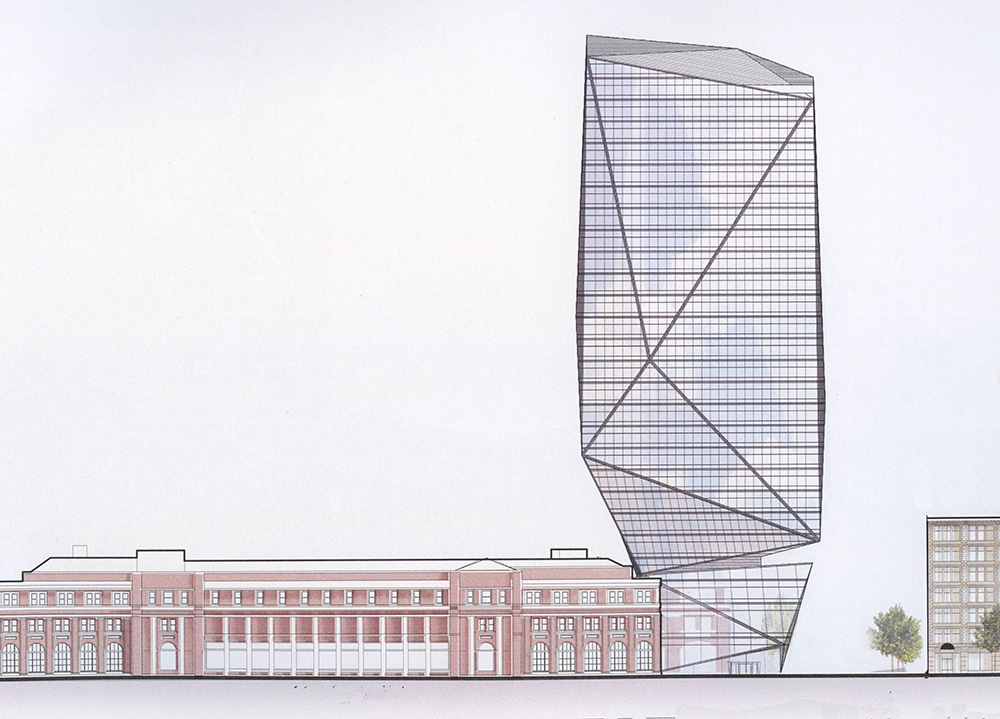

Like the original Penn Station, Waterfront Station’s owner wants to maximize its profits. First proposed in 2015, Cadillac Fairview aspires to build a private, ultramodern 26-storey office tower on a wedge of parking lot next to the station. It was quickly nicknamed the Ice Pick.

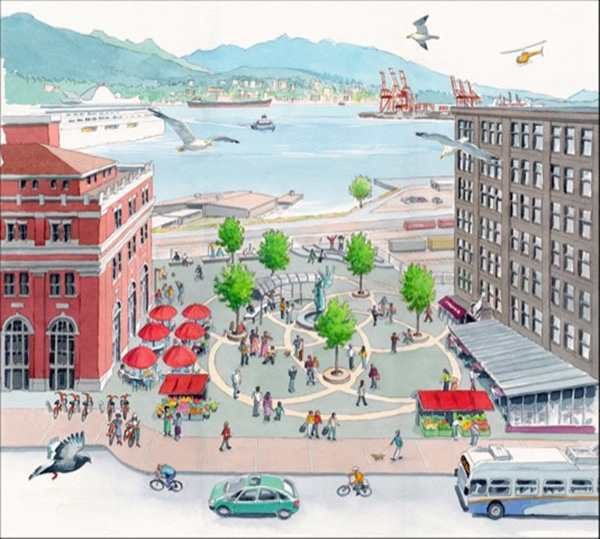

Cadillac Fairview has started, proposed and withdrawn different designs over the past six years. Whether you like the Ice Pick’s look, or not, is not the point. Its location between two historic buildings at the entry to Gastown has led the city’s advisory Urban Design Panel and its Heritage Commission to reject it. More fundamentally, since 2009 the city has had preliminary plans to replace the tawdry existing transit shed with a great, glassy public hall: a transit and visitor entry to Vancouver, with views of water and mountains, transportation and history, urban commerce and pleasurable public space. Something like Liverpool Station in London.

It’s part of an overall planning framework for the Downtown Waterfront. Full disclosure: I’m a member of the Downtown Waterfront Working Group of planners, architects and urbanists convinced that the city’s waterfront plan needs to be updated before consideration of any new developments.

The Cadillac Fairview office tower could severely compromise or eliminate the opportunity for a public transit galleria that would be the region’s fully functioning transit centrepiece for the 21st century.

Now there’s a new opportunity, involving all three levels of government. Last month, to help the country’s economic recovery once the pandemic is contained, Ottawa’s federal fiscal update promised to spend “up to $100 billion” on “smart investments that have value now, and well into the future.” The Globe and Mail quickly recommended “some big investments in public transit.” Here’s one:

The federal government joins with the province to buy Waterfront Station. Which will insure opportunities for transit and public improvements. (All other metro transit stations are publicly owned.)

Waterfront Station and its adjoining parking lot has a 2020 assessed value of only $68 million, down ten per cent from last year. Ottawa could provide the cash, or join with the province and city to trade for another downtown development site. We’ve identified two: a 1960s city-owned parkade in a prime location, and an underused federal property. Surely, there are others.

Public ownership of Waterfront Station would afford many benefits:

TransLink could improve transit connections for commuters, airport travellers and tourists on the adjacent cruise ships.

For visitors, Waterfront Station becomes the welcoming entry to historic Gastown.

Future station planning and operations become much easier and less expensive.

The parking lot becomes a public plaza with spectacular water and mountain views that define Vancouver.

It’s no crime for a private company to maximize its property values. But losing the opportunity to maximize public transit benefits for future generations— that would be a crime. ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: