[Editor’s note: We’re glad to publish this excerpt from veteran conservation activist Stephen Legault’s new book ‘Taking a Break from Saving the World,’ published by Rocky Mountain Books this year. The book covers the consequences of overwork, burnout and self-sacrifice in social change movements, and the possible solutions. It’s for all kinds of activists. Learn more about the book here.]

What do I mean by eddy out? It means to take a break. When you eddy out, you’re proactive in looking for a place to get out of the madcap, white-water rush you’ve been on and rest and recharge for a few days, a few weeks or a few months.

Central to this, and to be discussed later in the book about organizational support for resilience in the non-profit workplace, is that you have the option of stepping away from your work and then returning if you want to. If this option doesn’t exist through a formal leave of absence policy, through a sick leave provision in your contract or through the regulatory environment in which you work, then eddying out may well involve resigning. Before we get to that, let’s consider how you will know it’s time to cut the eddy fence.

Let’s also assume that you have a choice. You haven’t been dismissed, but you can feel yourself flailing, and despite your best efforts to brace, to bail and to get help to do so, you’re taking on too much water. How do you know it’s time to cut the eddy fence and take a break in quieter waters?

There is a concept in psychology called the “sunk cost fallacy,” and it means pretty much what it sounds like. “I’ve spent three years on this campaign? How could I leave now?” was a phrase that often crossed my mind in the final few months of my time at Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative. My internal dialogue sounded something like this: “After everything I’ve done? After all I’ve sacrificed, it seems a shame to turn my back on it now.”

“Of course,” says Peg Streep in Psychology Today, “this isn’t rational thinking... [If] going to work fills you with dread, staying even longer won’t help you cope with the time you now consider wasted or lost. But people do it anyway, all the time.” You’ve likely heard the phrase, “throwing good money after bad.” It means that investing more money into a losing proposition isn’t going to make it better. In this case, using the argument that you’ve already invested all this time and so you might as well stick it out is “throwing good time after bad.”

You can’t get time back. The time you’ve invested in a job that is no longer working for you is behind you now. The time you are considering continuing to invest, however, is in front of you.

Another phrase from popular psychology is “intermittent reinforcement.” First coined by B.F. Skinner, a Harvard-based behavioural sociologist and psychologist, it refers to a condition where the subject responds to occasional positive rewards the same way they would to continuous positive rewards. Dr. Skinner did his research on rats, which, despite not being rewarded each time they pressed a lever for food, tried even harder.

According to Peg Streep, we’re not that different from rats in this way. We might know that things are pretty terrible at work, or we might be so burnt out that we can no longer cope, but from time to time we get a reward, and that makes us try even harder.

From my own experience, there are some clear indicators when it’s time to leave. It’s important to be highly critical of your own perception of these markers. It helps to have a close friend, partner, coach or personal board of directors available to hold you to account and insist on reflective consideration on these matters. Sometimes, when we are facing short-term challenges, we may feel any or all of these, but that doesn’t mean at the first onset of anxiety we should bail out of the boat. These are perfect times to eddy out.

These indicators should be observed for their frequency and duration. A good sign that you’re in trouble is if you experience these things over and over again, with increasing frequency, and have a harder and harder time recovering from them. If that’s the case, you may need to start scanning the shore for a place to rest.

Looking for flat water

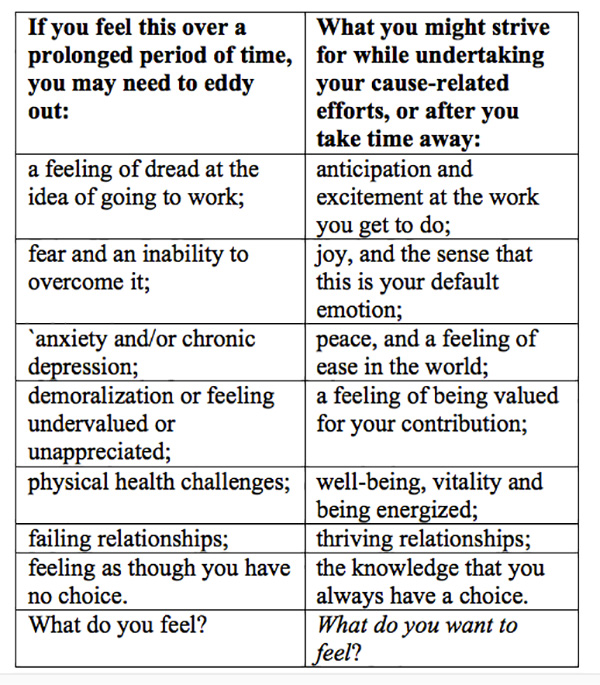

Here’s a partial list that you might add to, and the corollary that we might strive for, during our time working to save the world, or once we’ve made the decision to cut the eddy fence.

Most of these are pretty straightforward but gallingly entwined. None of us should expect to feel energized by our work or our volunteer efforts all the time, just as nobody should expect joy, peace or a feeling of ease to be present at every moment of every day. That’s not realistic. The key here is to assess what your default feeling is. If day after day you drag yourself out of bed, feeling a sense of dread that you have to go to work, or if you’re constantly feeling demoralized once there, then you need to do something to change that default setting.

Feeling demoralized may lead to anxiety or depression. Failing relationships, with a spouse, your family or friends, can lead to mental or physical health challenges. If you go to bed at night with a knot in your stomach because the thought of going to work the next day makes you feel ill, or if you can’t sleep, or when you do you’re plagued by nightmares, you need to pay attention to those signals. If you wake in the morning and don’t want to get out of bed and face the day at the office, that’s a pretty strong signal. We all have days like this, but if this is commonplace for you, says Jacquelyn Smith, in Forbes magazine, you should probably consider cutting the eddy fence.

Earlier in the book, I asked, “Do you already know that it’s time to eddy out?” In his book When to Jump, author and coach Mike Lewis explores this question in detail. He urges us to “listen to our little voice.” In examples from a dozen different writers, he explores this topic in some depth.

Fear will keep you from acknowledging what you almost certainly already know. This is a theme that I’ve noted in reading dozens of articles on the topic of when to quit a job. We can see the writing on the wall, but sometimes it’s in a different language that we must first learn before we can understand it. Our guts are telling us something, but we’re too afraid to listen. We’re comfortable, or at least familiar with our situation, even if it’s difficult or painful at times. We are accustomed to that pain, and even rely on it to an extent to help us create the story of who we are and why we do what we’re doing. We brag about it. “Oh, I’m so busy right now. It’s just crazy,” we tell each other in a strange competition to see who is carrying the most stress and fatigue. In a perverse way, we celebrate each other’s stress.

We can be looking straight at the sweeper — a log just below the surface of the water — but we don’t see it. We have to take time to read the river; to decipher what our “little voice” is telling us. We need to eddy out.

Solo or tandem paddling

You don’t have to paddle these heavy waters alone. As noted previously, find someone — an individual, a coach, colleague, mentor, friend, life partner or a small informal group — who can help you maintain perspective. “You never actually jump alone,” writes Laura McKowen in her essay in When to Jump.

My wife has been my greatest support. Even though it would mean a prolonged period of economic uncertainty, she encouraged — no, strongly encouraged — me to cut the eddy fence. It’s important to have someone in your boat who isn’t afraid to call you on your BS. Supporters like David Thomson, my long-time, on-again, off-again coach and mentor at Training Resources for the Environmental Community, and Ed Whittingham, former executive director at the Pembina Institute and Friday-beer-drinking buddy, offered cool-headed, honest and sage advice.

Then there’s a moment when you know. It may be deeply uncomfortable. You’ll want to tamp it down and deny it. Don’t. As someone who has dabbled in meditation for most of my life, I’m familiar with these moments when the discomfort in our mind permeates our entire being. When meditating, we’re counselled to breathe into this discomfort, to “invite it in for tea,” to embrace it, learn what it has to teach and let it go.

Most of what makes us uncomfortable is related to the story we tell ourselves about who we are and why we are here, and what we would be if we didn’t have the crusader mantle to wear. The rest is almost certainly fiction created by our fear that will never come to fruition and that is merely part of our mind’s way of keeping us from cutting the eddy line. It’s important to train ourselves to face the cold hard facts of our circumstances and not buy into the stories we tell ourselves about who we are, what we do and why we are doing it.

“Coping is what people do when they try to muddle through,” says Seth Godin in The Dip. “They cope with a bad job or a difficult task. The problem with coping is that it never leads to exceptional performance. Mediocre work is rarely because of lack of talent.... All coping does is waste your time and misdirect your energy. If the best you can do is cope you are better off quitting. Quitting is better than coping because quitting frees you up to excel at something else.”

Godin offers one possibility, and in the end, it may be the correct course of action for you. Quitting is one option we’ll explore, but it shouldn’t be your first option. What’s important, however, is to explore both your decisions and your motivation. Can you take a break? Do you have some banked overtime saved up? Often we find ourselves beginning to burn out, but we haven’t considered the most basic of ways to revitalize our efforts: take our vacation time.

But sometimes that isn’t enough.

“Pride keeps people in careers,” says Godin, “years after it’s become unattractive and no fun.... Are you too proud to quit? One of the reasons people feel really good after they quit a dead-end project is that they discover that hurting one’s pride is not fatal. You work up the courage to quit, bracing yourself for the sound of your ego being ripped to shreds, and then everything is okay. If pride is the only thing keeping you from quitting... you’re likely wasting an enormous amount of time and money defending something that will heal pretty quickly.”

Godin’s book is a fabulous and blessedly short read or listen for anybody looking for guidance on whether or not to quit. (That said, I could save you a few bucks and say that, if you’re buying a book about deciding if you should quit, you’ve likely already made up your mind.) I’m giving you another possibility to consider.

In the end, a lot of people can give you advice, a few people can provide you with guidance, but only one person can really understand what you need to be happy and live a fulfilling life: you. “The question I’ve come back to again and again in my life is, ‘What would I do if I wasn’t afraid?’” Sheryl Sandberg said in When to Jump.

What would I do? I’d cut the eddy fence. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: