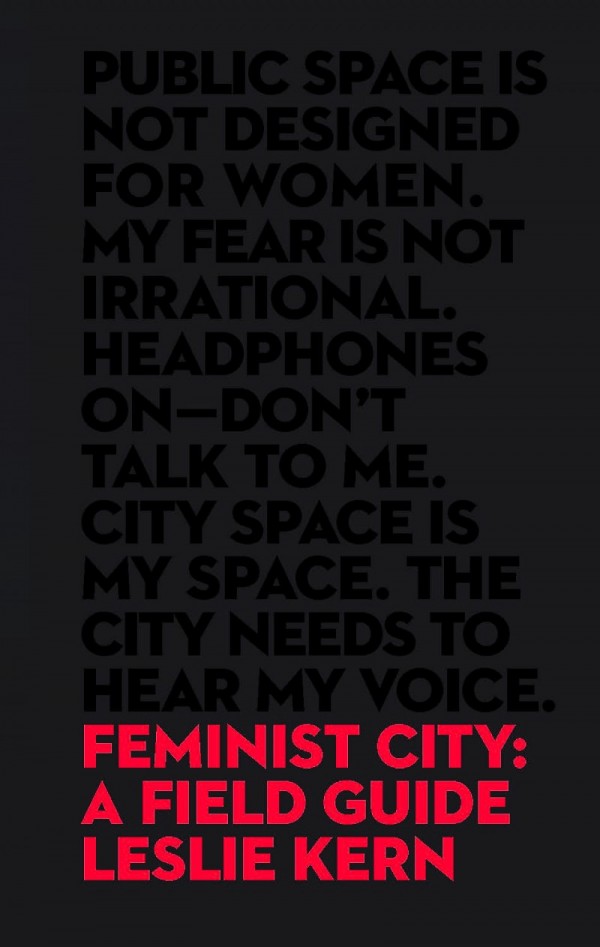

- Feminist City: A Field Guide

- Between the Lines (2019)

If your city feels hostile to women, it’s because men made it that way.

Women are often taught that dodging trouble in the city is their responsibility. Don’t go out alone. Don’t dress like that. Stay away from that neighbourhood.

But since the 1970s, feminist geographers have been exposing the modern city for what it is: an environment made by men for men. That means that anyone who doesn’t have the body of a straight white guy will find it harder to do anything, from taking transit to eating a snack on a bench in peace.

In a recent Guardian story, a Viennese architect used the rebuilding of cities after the Second World War as an example of the men-first phenomenon.

“They designed cities like there would be no other people than men going to work in the morning and coming back in the evening,” said Sabina Riss. “Everything else in between, they kind of had no idea. And because they are the people who design cities, they are in charge.”

In the new book Feminist City, feminist geographer Leslie Kern of Mount Allison University in New Brunswick follows in the footsteps of others in her field. If you’re unfamiliar with this area of study, the titles of key writings give you a taste of the ground covered, such as “On Not Excluding Half of the Human in Human Geography,” a paper by Janice Monk and Susan Hanson, and The Sphinx in the City: Urban Life, the Control of Disorder, and Women by Elizabeth Wilson.

What Kern offers is summed up neatly in her book’s subtitle: A Field Guide. At 192 pages, it’s a slim and handy volume that dissects the dos and don’ts doled out to women trying to live their lives in the cities of men (though the vast majority of her findings come from cities in the Western world).

“Any settlement is an inscription in space of the social relations in the society that built it,” wrote feminist geographer Jane Darke. “Our cities are patriarchy written in stone, brick, glass and concrete.”

But tackling this urban problem is more than a matter of asking “women’s questions,” writes Kern. It’s about understanding the power dynamics that exist in our cities.

“The primary decision-makers in cities, who are still mostly men, are making choices about everything from urban economic policy to housing design, school placement to bus seating, policing to snow removal with no knowledge, let alone concern for, how these decisions affect women,” writes Kern.

Aside from women, how does a city accommodate the poor, people of colour and people of different gender identities and sexual orientations?

An able-bodied white guy would be able to walk through Holt Renfrew without staff thinking they’re in there to steal something. Or be given keys to a washroom without scrutiny. Or stay for more than an hour at a Starbucks without being called out for loitering or freeloading. Can the same be said for, say, a black North American?

“Many of these barriers are invisible to men, because their own set of experiences means they rarely encounter them,” Kern writes.

Here’s a peek into some of the barriers Kern explores in her field guide.

How cities try to keep women in place.

From the beginning, the modern city was considered inappropriate for women. They needed to be kept near home and hearth and away from the urban poor and sex workers, called “fallen women.”

But 1870s Paris saw the invention of the department store, an urban space that was “appropriately feminine.” New York too had its Ladies’ Mile of shops, as well as districts with museums and art galleries for the fairer sex.

These might have been new spaces to explore, but they segregated women and reinforced existing gender norms. Women were meant to be entertained and to consume, encouraged to shop for clothing, décor and art, fulfilling their roles as “caretakers of the hearth.”

These ideas still linger, argues Kern, who studied how condo ads depict women in Toronto. Have a look at condo ads near you: do you see women going to work, or are they shopping, eating, drinking and socializing?

It’s impossible to blend in when your body has suddenly become public property.

Sociability is one popular measure of a successful city, as any disciple of the Jane Jacobs gospel of urban life will tell you. But an equally important measure is the ability to be left alone.

And women’s personal space in cities is regularly violated by touch or words.

“A woman alone is presumed always available to other men,” writes Kern.

She cites the icky article “How to Talk to a Woman Wearing Headphones,” which puffed up self-declared pick-up artists when it went viral in 2016. The author insists that even “crazy feminists... will pretty much instantly melt and be nice when a confident guy walks up and says hello,” assuring men that women secretly want men to interrupt what they’re doing.

Pregnancy was a different kind of visible marker that exposed Kern to both the touch and words of strangers, with people rubbing her belly (“as if it said ‘rub here, please!’”) and offering unsolicited advice on how to be a good mom.

“As a woman, the privilege of being able to mind my own business is a rare one,” writes Kern, adding that private time in public is especially important for moms. “Perhaps being alone while out in the city is so precious for women because at home we’re always in demand.”

Just because it’s legal doesn’t mean it’s allowed.

Breastfeeding in public might be protected by human rights laws in Canada, but Kern writes that she still felt uncomfortable nursing, having once been yelled at for simply having a stroller.

Strong conventions govern what actions can take place, where, and by whom.

In some places, you can’t even wait for a friend because of who you are. In April 2018, two Black men were handcuffed and arrested in a Philadelphia Starbucks after the manager called the police because they hadn’t bought anything yet.

Interactions like these tell us who truly belongs in a space.

Fear has a cost.

What women are afraid of most in the city, according to research, is dangerous men.

The consequences of this fear come in many forms: social, such as having to decline events in the city that go late; psychological, such as second-guessing one’s choices or self-blaming if something bad happens; and economic, such as not enrolling in night classes or choosing to live in a pricy neighbourhood because it appears to be safe.

And yet women who are victims of harassment or violence are often asked what they were doing in that area or being out alone.

“We anticipate these questions and they shape our mental maps as much as any actual threat,” writes Kern.

“At the end of the day these limitations and costs and stresses amount to an indirect but highly effective program of social control. Our socially reinforced fears keep us from fully inhabiting the city and from making the most of our lives on a day-to-day basis.”

How cities were designed to help men get around.

“All forms of urban planning draw on a cluster of assumptions about the ‘typical’ urban citizen: their daily travel plans, needs, desires, and values,” writes Kern. “Shockingly, this citizen is a man.”

Most public transit systems, therefore, were designed to accommodate the typical rush hour commutes of nine-to-five office workers.

However, commutes that require detours or multiple stops, like that of a primary caregiver, aren’t as smooth, nor are trains, buses and underground corridors always suited for people with strollers or shopping. Kern also cites research that shows women pay more transportation costs than men, a kind of “pink tax”; full-time moms and other caregivers, for example, ride public transit for greater distances and take multiple trips a day.

Public washrooms suck for women.

If a women’s washroom has a long line, we should ask why a man did such a poor job of designing it.

Women need more time to use the washroom than men. Some reasons are biological, such as addressing menstruation or always needing to sit when using a toilet. Some are cultural, such as needing more time to remove clothing or the fact that women often are the ones who take care of family members who need washroom help.

If a design isn’t user friendly, let’s not blame the user.

Lesson: it’s possible to reshape cities for all.

The United Nations’ global strategy for gender equality embraced the practice of “gender mainstreaming” in 1995, meant to ensure that policy, legislation and resource allocation isn’t just based on the needs of men.

In Vienna, which adopted the practice 10 years earlier than the UN, some developments have on-site childcare and health services to make life more convenient for working women with children. Lights are installed to increase safety and reduce anxiety for women, sidewalks are widened for accessibility and, in the case of two parks in 1999, volleyball and badminton courts were added to counter the boys’ dominance over the basketball courts.

Gender mainstreaming touches everything down to snowplowing. The location and time of day a city chooses to plow snow tells you a lot about who it considers to be important. (Surprise! It’s usually the working man.) Stockholm though has been prioritizing sidewalks, bike paths, bus lanes and day care zones through its “gender equal blowing strategy,” recognizing that women, children and seniors are more likely not to drive.

Though even with gender mainstreaming, there is the potential mistake of reshaping the city for a narrowly imagined female who isn’t representative of the whole.

These imbalances are everywhere, and Kern encourages us to shine a light on them.

“I don’t want to be a feminist super-planner to tear everything down and start again,” she writes. “But once we begin to see how the city is set up to sustain a particular way of organizing society — across gender, race, sexuality, and more — we can start to look for new possibilities.” ![]()

Read more: Gender + Sexuality, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: