[Editor's note: Salmon: A Scientific Memoir investigates salmon as an iconic species for the Pacific Northwest Coast. Each chapter focuses on a portion of the salmon's journey to and from their natal streams; on one of the five Pacific salmon species most commercially important to North Americans; and on the different ways scientists study the fish. It's also about the scientific journey of ecologists, archaeologists and fisheries biologists and how the labs gathering data today echo coastal indigenous people who have harvested salmon successfully since the end of the last ice age.

The following is drawn from Salmon: A Scientific Memoir by Jude Isabella, published by Rocky Mountain Books.]

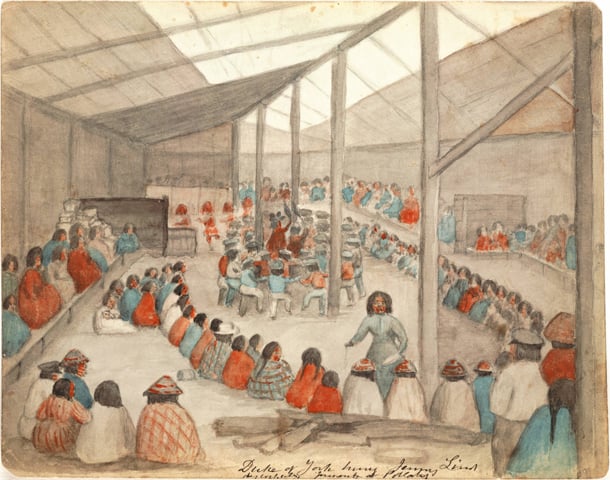

"Potlatch" is an Anglicized version of the Nuu-chah-nulth word pachitle, a ceremonial feast with two huge benefits for the people who practised it. Potlatch ceremonies both redistributed wealth and maintained a healthy ecosystem and are in part what made the Pacific Northwest Coast famous in anthropology circles. The more a community had to give away during potlatch ceremonies, the richer the community. The wealthiest had access and rights to exploit natural resources, but they also had the responsibility of regulating the take to ensure a steady supply to the community. Potlatching was practised up and down the coast, each community had its own variations, but the core ideal -- reciprocity -- was the same.

In studying up on the ritual, I dove into H.G. Barnett's 1938 dissertation "The Nature and Function of the Potlatch." I was grateful to discover it is not painful to read. In fact, if Barnett is any indication, researching and writing a dissertation was more fun in 1938 than it is today. No slogging through a long genealogy of anthropological writing, redefining every anthropological term ever found in print. Barnett simply dips the readers into a world, in this case Coast Salish, where wealth came from the land and sea, the rich were expected to "pay" what they could afford and the people expected everyone to give back as much or more than was received.

In the reciprocal economic system of the world Barnett found, generosity was highly rewarded. "Obviously, the system works only because everybody -- everybody who is included in it -- has the same idea; namely to give back as much or more than has been received," Barnett wrote. But this reciprocity, oddly, occasionally begot rivalry, too, with rival potlatches becoming contests of destruction. And for people with slave origins, no matter how many potlatches they hosted, they would never rise above their ancestry. No matter the culture, each of us can fall victim to pride.

We also can't resist play, something else Barnett found in the potlatch, with wrestling, racing and eating contests, as well as clowning around and comedy. "Sometimes the food intended for one man is eaten by those who pass it along," Barnett writes. Even a potlatch for the dead is "interspersed with rollicksome incidents."

It sounds a lot like a scientific lab.

Riddles of stone

I reread Barnett as I was getting ready to visit Megan Caldwell, an archeology doctoral student at Simon Fraser University studying societies on the Northwest coast before European contact. Her focus in the spring of 2011 were remnants of fish traps used by the Tla'amin people. I'd looked in on her work before, and this time, as we met at of one of her Tla'amin sites, Barnett's writings recharged my sense of wonder at the grand archaeological project.

I catch up with Caldwell at Gibsons Beach, a beach Barnett likely strolled as well. Barnett interviewed Tla'amin Elders, none of them are alive today, but their grandchildren are and I'm here to chat with them. Caldwell, Nyra Chalmer, another graduate student, and I measure and map some traps. These are stone traps, different from the traps in Heiltsuk territory. And this is what puzzled another SFU scholar, Anne Salomon, when she saw her first ancient clam gardens in Desolation Sound, not far from Gibsons Beach. The Tla'amin may have had dual-purpose technology -- fish traps and clam gardens intertwined.

In Desolation Sound, Salomon saw what looked like a jumble of fish traps and terraces for the herring and salmon runs, along with the clam resource. Waiatt Bay has no fish run. It was perfect for gardening clams, and the people likely honed the technology to that environment. Likewise the environment here dictated the technology.

Survey done, we pack up and drive five minutes to the Tla'amin main village. We stroll the front "yard," a jumble of sunken fish traps that echo the pre-Colombian-era remains we've just measured at Gibsons Beach but are famous among archaeologists because they're so extensive and obvious. Stone walls that form traps scallop the shore for a kilometre -- these traps still catch salmon and other species in season. A breeze riffles the water, disrupting the sun's warmth, chilling our bare arms. Twin markers of the relentless march of the outside world frame the site: a church squats on the waterfront and, in the distance, a paper mill bellows steam.

We walk up the beach and onto the road to the band office where Michelle Washington, the land use planning coordinator for the Sliammon Treaty Society, has worked with the SFU archaeologists from the beginning of excavations in the territory. She introduces herself as Washington but also by her traditional name, Siemthlut. She introduces me to her co-workers and gathers up some coffee mugs for us as we retreat to another room. Washington's brown eyes sparkle. She has an open face, smiles easily and has a husky laugh that's a gift to those around her. Her long, black hair is swept up in a ponytail that streams down her back.

Washington is 40, young enough that in many families she might have grown up ignorant of Tla'amin traditions, but as a girl, she was curious about the old ways and spent time with her grandparents. Over the years, she interviewed lots of Elders, learning about the interplay of the environment and the people: stone traps invited in the herring precisely when salmon stores were low (early spring) and villagers needed an influx of fresh food.

"When I was a kid, this time of year was alive, this village was alive," she says, placing a couple of thick manuscripts she grabs from a shelf on the table. One is a land use survey she authored. "Everybody had their smokehouse ready, their herring racks ready, the kids were all down the beach, you know little kids just had ice cream buckets, the bigger kids had bigger buckets, because you could go down into the little pond in the intertidal zone and scoop up hundreds of herring in one scoop and run it to your house. That's not that long ago: 1984 was the last year I remember that happening."

But the damage to Indigenous fisheries began long before that. And when people stop gathering or cultivating a species -- like herring -- information is lost forever. Especially when language is also lost. Anthropological writings, like Barnett's, fill in gaps and confirm oral histories -- though most early researchers failed to see signs of active management. Washington is keen to make sure the contemporary story of her people becomes part of the historical narrative of the coast. The Tla'amin weren't just lucky, endowed with mild weather and abundant resources, she says, they worked the land according to ecological principles developed by their ancestors. They cultivated careful relationships, both nonhuman and human.

'It is a good law'

High-class Coast Salish families inherited rights to abundant salmon runs, and they consolidated wealth by marrying other elites. Heh goos -- "head men" in the Tla'amin language -- made decisions on when and how to fish, and their status was legitimized through the public ceremonies of the potlatch, when they gave away their wealth. The lower-class Coast Salish had little social mobility. Status, for the most part, was inherited and changes in the social hierarchy were rare. The lower class had a lot of incentive to cooperate with the wealthy. Soon after potlatches were outlawed in 1885, the chief of the Kwakwaka'wakw -- ancestors of the tribes belonging to the Laich-Kwil-Tach Treaty Society -- told anthropologist Franz Boas: "It is a strict law that bids us distribute our property among our friends and neighbours. It is a good law."

Potlatches not only distributed wealth -- a finite natural resource -- they also distributed knowledge, which is not finite unless it gets lost. That's always a danger, especially if it's not written down. Washington is teary when she talks about knowledge disappearing. The Coast Salish way of living was hard won and will not easily be retrieved. "My Granny used to say something that I never quite understood until I got older," Washington says. "She would look at expensive homes with manicured lawns and say, in our language, 'Oh those poor people, they have no medicines or food in their yard. How are they going to feed themselves and take care of themselves if anything happens?'"

The scientific work on sockeye, chinook, coho, chum and pink, and on their relationship with their environments, is painstaking, expensive and highly structured. It is also the only means of translating Indigenous and community knowledge into the language of the dominant culture. Science gives language to a way of living that requires multiple means of communication but often few numbers or words. For the Coast Salish Elders, to know salmon -- or any other fish, shrub or tree -- was to think like them, and to think like them required knowing them -- a circular path. What's required is daily observation. The act of urbanizing removes us from intimate contact with the natural world, interrupting the circle.

Seceding from that kind of knowledge is dangerous.

Labs as potlatch society

The dominion government banned the potlatch to open the way for a new, capitalist system of rewards and punishments, and yet scientific labs today abide by their own kind of potlatch. In the corner of our culture that addresses the urgent problems of disease, climate change and food scarcity, we still value sharing. Successful labs have generous principal investigators -- our version of Heh goos -- who have access to knowledge, equipment, funds and other "elite" principal investigators in the same field. Generous principal investigators beget generous graduate students, who move on to establish their own labs, or work in industry or in government, and keep ties with their old labs (that's the intermarriage part).

A lab's generosity and reciprocity make it resilient. As long as society values the knowledge a lab produces, it remains prestigious -- and stable. This is sometimes why scientific theories that need to die might take a long time to do so -- they come from a resilient lab. In such cases, a theory only dies when the investigators die. And anyone who has spent time in academia also knows it's full of the best about humans (generosity, cooperation and fun), as well as the worst, often rife with unhealthy rivalries and too much pride.

Scientists dislike hearing that what they do is a cultural endeavour; they think it's objective, nonbiased and above human emotion. But having communed with so many researchers pursuing fascinating hypotheses and discovering vital information in my time as a science journalist, what strikes me as most important is how each lab reflects a way of being in the world. Their economy of knowledge is a reciprocal economic system that humans fall back on again and again when wealth is tied to something other than the abstract idea of money, freed from the marketplace.

The making of science is an imperfect system because humans are imperfect -- and there will always be cheats -- but it is a system with straightforward rules, sometimes as simple as "you get what you give." ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: