- Mac Pap: Memoir of a Canadian in the Spanish Civil War

- New Star Books (2013)

- Bethune in Spain

- McGill-Queen's University Press (2014)

These two recent books portray the war from Canadian viewpoints -- those of Dr. Norman Bethune, who ran a mobile blood-transfusion service for the Republican forces, and Ronald Liversedge, a working-class Canadian who fought in the International Brigades with the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion. Neither man had a very good war, and in some ways they foreshadowed the Canadians of later generations who went off to fight in other people's wars.

If the two books have a common theme, it's that wars' outcomes don't depend on courage or willpower or being on the right side of history. They depend on equipment and experience.

Republican Spain was desperately short of war materiel while Franco's forces enjoyed masses of weapons and trained "volunteers" from Germany and Italy. Most Spanish army officers followed Franco, leaving the government to fight a war with ill-armed amateurs, whether citizen soldiers or international volunteers. Liversedge and Bethune at least had experience in the trenches of the First World War, so they knew what they were getting into.

Technically, Liversedge and his fellow volunteers were criminals. Canada had passed a law forbidding its citizens from fighting in other people's wars, although some senior Ottawa mandarins didn't mind if they got to Spain. With any luck, they reasoned, these troublemakers would die overseas and save the Dominion from some future bother.

Liversedge did not oblige them. A British-born veteran of the First World War, he had migrated to Canada and found the same hostile conditions for working people that he'd left in Britain. After a couple of years of occasional farm labour, he'd been hit by the Depression, become a Communist, and joined the On to Ottawa Trek.

Working as a miner and party organizer in Atlin, he heard about Spain, returned to Vancouver, and volunteered to go overseas. On May Day 1937, with just five dollars for travel expenses and a passport marked "Not valid for travel to Spain," he left a rally in Stanley Park and boarded a train from Vancouver to Toronto.

A poor 'Canadian cousin' in combat

By roundabout ways he and other volunteers got to France and then to Marseilles, where they boarded a Spanish ship bound for Barcelona. An hour before arrival, the ship was torpedoed by an Italian submarine. Half the crew and 163 volunteers died. Liversedge was lucky to survive; he came ashore hypothermic in just his pants and underwear.

His next two years were a mix of combat and bureaucratic politics. The Americans wanted to absorb the Canadians into the Abraham Lincoln and George Washington Battalions. Other units wanted to recruit North Americans whose native language was Polish, Hungarian or Czech. Liversedge joined up with the Washingtons.

He soon learned "there was still a tendency on the part of a certain section of the American political and intellectual coteries to regard the Canadian cousins as poor relations." Nevertheless, he and the other Canadians were determined to fight as a Canadian unit, and eventually formed the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion.

It fought with distinction in several campaigns and battles, almost always outgunned and without air support. Ill-fed and badly equipped, the Mac-Paps were among the Internationals who gained a rare reputation: when wounded and hospitalized, they deserted back to their units in combat.

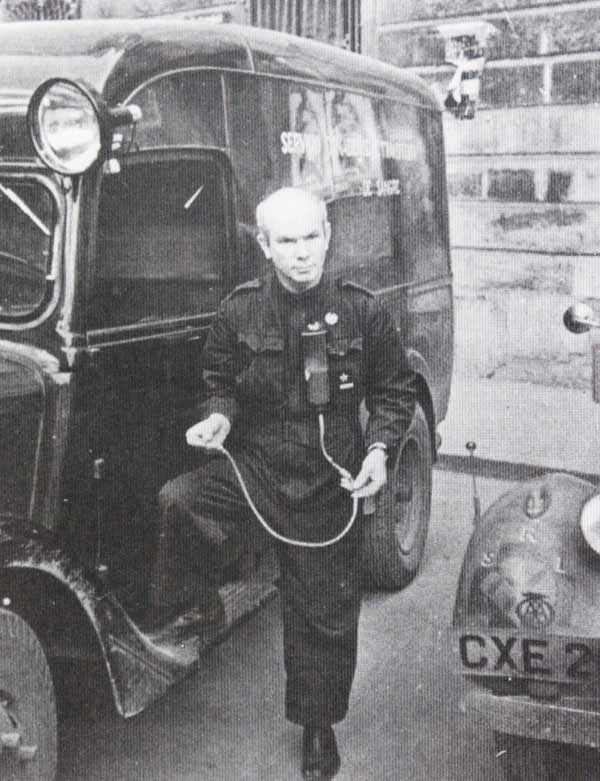

Bethune, meanwhile, fought a different war. The Canadian Communist Party raised money to send him to Spain as a party member who was also a prominent surgeon. Once there, he found his surgical skills not really needed, and invented a new role -- leading a team delivering blood for wounded soldiers right at the front.

Bethune's blood bank

It was a dramatic advance in combat medicine, but it required expensive equipment and imagination when the equipment wasn't available. Bethune was constantly negotiating with both the Spanish authorities (who didn't like him very much) and his Canadian sponsors (who weren't sure where all their money was going).

Amid the bureaucratic wrangling and endless correspondence, his mobile blood bank actually delivered the goods and saved many lives. Bethune personally saved still more lives on the retreat from Malaga: when he encountered thousands of refugees fleeing the Fascists, he put as many mothers and children as he could into his truck and sent them to safety while he trudged the road with the others, under constant attack from air and sea. When the truck returned, he put more refugees into it.

The experience strengthened his hatred of fascism, but he still ran into political trouble. His Spanish staff didn't like him, and he could certainly be unlikeable, being unable to speak the language, short-tempered and a heavy drinker. Worse yet, he was sleeping with one of his staffers, and spending money faster than the Canadian Communist Party could provide it.

He'd been a good propagandist as well as combat medic, delivering radio talks in support of the Republic. He'd also authorized the making of a film, Heart of Spain, about his mobile blood-transfusion service. When the party called him home, it was to help promote the film on a North American fundraising tour. He pretended he'd be returning to Spain, but the party had no intention of sending him back.

Death and glory

Applauded across the continent, Bethune knew he was in disgrace with his comrades. But he managed to get support for a mission to China in support of Mao Zedong's Eighth Route Army, which was fighting the Japanese. That mission took him to death and glory.

Ron Liversedge had no such glory. When the Republic sent the International Brigades home, he went with them. Back in Canada, he returned to working-class jobs in B.C. He didn't write his memoir until years later, as a kind of therapy for his drinking problem.

It ended up in the hands of an academic who did nothing with the manuscript for decades. We are lucky to have it now as a remarkable document by an ordinary Canadian caught up in the prelude to a catastrophe he foresaw and tried to prevent.

The Bethune book, by contrast, reflects recent scholarship on a world-famous figure, enriching Roderick Stewart's brilliant 2011 biography Phoenix: The Life of Norman Bethune.

The thousand-yard stare

Do the experiences of Norman Bethune and Ron Liversedge tell us anything about our present lives, 75 years and many wars later?

Maybe more than we would like them to. I recall being a young college teacher in the 1970s, and occasional students who came into my class were U.S. Army veterans like me. Unlike me, they'd signed up because they wanted to see what a real war was like, and that was Vietnam. More Canadians joined the U.S. Army in those years than American deserters and draft dodgers came north.

So it was in such Canadian Vietnam veterans that I first saw the thousand-yard stare of men who have seen too much. (In hindsight, both Liversedge's postwar drinking and Bethune's death in China look like expressions of post-traumatic stress disorder.)

I saw that stare again decades later in a student-veteran back from Afghanistan. Whether their motives are idealism, adventure, or duty, Canadians who go to war are likely to come home scarred. Now some young Canadians are disappearing into the Middle East, into Syria or Iraq or Algeria, driven by the dream of a religious utopia. They may be closer in spirit to the Mac-Paps than they would like to admit. They are certainly as unpopular as the Mac-Paps were, and perhaps for similar reasons.

Canada in the 1930s was a nasty country for many Canadians; despite all our progress since then, we have far to go. The Ottawa mandarins who despised the likes of Ron Liversedge and Norman Bethune included Duncan Campbell Scott, the poet-bureaucrat who wanted to exterminate the First Nations as cultures by putting their children in residential schools. They didn't want to accept one Jew or Asian more than they were forced to, and their modern descendants aren't too keen on Muslims.

So if young men growing up in 21st-century Canada suddenly take off to fight in Syria or Algeria, it's too easy to moralize about what treacherous little jerks they are. As big as this country is, it evidently can't provide spiritual room for some, just as it couldn't provide economic room in the 1930s.

Even if our aspiring young jihadis are damned fools (and I think they are), they're also our kids. If we can make a truly civilized country here, they will be less likely to take off in search of a Marxist or sharia utopia.

And they won't come home with thousand-yard stares. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: