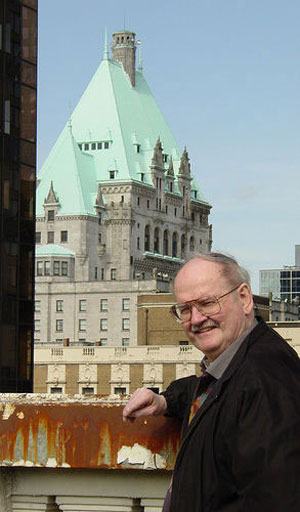

When an old-fashioned historian dies in these times of instant news and fleeting celebrity, it's usually little noted. But the death of Vancouver's 75-year-old Chuck Davis in Nov. 2010 had been preceded -- since his earlier announcement he had just weeks to live -- by a huge wave of public tributes. Those who knew Davis well -- and I was one -- understood that someone unique was leaving the scene. The history of Vancouver and Davis are, and will always be, inextricably bound.

And now there will be a communal opportunity to remember Davis, at his memorial this Saturday, Mar. 26, at the Hotel Vancouver, beginning at 2 p.m.

When he stepped off the train in Vancouver in Dec. 1944, the nine-year-old looked around, saw green instead of the white of mid-winter Winnipeg, and said to his father, "I think we've come to the right place." But his father, fleeing an unhappy marriage, may have soon had other thoughts. They lived, dirt poor, in an unheated squatters shack on Burrard Inlet until it burned down. And when thieves stole his father's entire stock of warehoused candy -- he'd planned to open a candy store in East Vancouver -- the two were left destitute. For years, father and son bounced around Vancouver, Burnaby, and Ontario -- taking odd jobs, living in a series of dumps, trying to survive.

By age 17, Davis had had 21 jobs, and somewhere in Grade 8 his official education ceased. Facing a bleak future, he joined the Army in 1953, and soon discovered his easy-going voice and his extroverted nature suited the prime medium of that time -- radio. For the next 25 years his name was connected to various local radio and TV stations -- from CHEK-TV to CBC Radio to CKVU. Everyone knew, if not his face, Davis's manner and broadcast voice: mellow, self-deprecating, funny, observant, wry and -- most of all -- intensely interested in things. His was a boyish curiosity -- like "WOW!"

When he and I first met in the early '70s he had just made the discovery that would alter both his and Vancouver's history. He'd had a gig as an occasional columnist for The Province then. And while driving, as he put it, "for the 10,000th time over the Burrard Bridge," he noticed its unusual Art Deco architecture, and asked himself what was behind the bridge's design. He went to the city's gloomy, almost moribund archives --- a room in City Hall then, full of material collected by archivist Major J.S. Matthews --- and produced a 900-word story, the first of 194 Vancouver historical accounts he'd write for The Province every Sunday for years. Then came Chuck Davis's Guide to Vancouver (1973).

Deadline? What's that?

Around this time, I had the idea to do a guidebook on children's activities around Greater Vancouver. And so we decided to pool our common interest -- he'd married his wife, Edna, in 1965 and had a young daughter, Stephanie -- and co-write what would subsequently become the best-seller, Kids! Kids! Kids! And Vancouver (1975). But Davis's restless enthusiasm quickly distracted him from our project to a newer -- and more to his historical liking -- book project aimed to coincide with the upcoming U.N. Habitat Forum of 1976. That project would become, in time, The Vancouver Book (1976), a massive compendium of information and stories on every aspect of the city, and the primary reference book on the city to this day. Since I was that book's associate editor and shared an office with Davis, I was soon initiated into the Chuck Davis method of collecting, storing, retrieving, and writing what turned out to be a 500-page tome. He had no method! Budget. What budget? Deadline. What deadline? Oh, had he seen recently the file I'd dug up on the origins of Stanley Park? Nooo. And we'd survey a helter-skelter scene of piled boxes and misplaced files and take-out food containers and newspapers that attained, in time, geologic levels of strata. And so we'd start digging. (All his offices attained a Baghdad-on-a-Bad-Day appearance.)

Completing a bullet-stoppingly thick book on Vancouver might have been sufficient for most mortals, but not for Davis. There were subsequent annual Vancouver history date books. And books on Vancouver's suburbs. And then his 900-page The Greater Vancouver Book (1997), which proved to be a colossal financial failure that spelled near bankruptcy for Davis and his Linkman Press associates. Davis's obsession about the city carried on, however, unabated. No incident, no fact, no scrap of trivia about anything to do with the city was too insignificant not to stuff into his pockets which his wife had long learned to empty before things were lost in the laundry. Davis had, it turns out, bigger fish to fry: The Metropolitan Vancouver Book. It would be the culmination of his 40-year obsession, his magnum opus.

Ambitious dreams

Davis was a man of enormous, happy ambitions. He was never afraid of thinking big. He told me one day while we were doing The Vancouver Book that he’d decided to walk -- as a matter of research -- every single block of every single street in Vancouver. Only to admit later it wasn't feasible. Years later, he informed me he'd decided to create a gargantuan web-based encyclopedia, listing every single place name on Earth. That, too, finally succumbed to reality.

It was impossible not to love a guy with so many dreams, and so little concern about constraints. And like others whose imagination sometimes outpaced practicalities, Davis was famously absent-minded. He'd leave a luncheon and forget where he'd parked his car. Regularly. An underground parking lot -- any underground parking lot! -- was his special nemesis. He once told me that he'd driven from his East Vancouver home halfway to Surrey on Highway 1 before a passing motorist, honking and pointing to his vehicle's roof, had reminded him he'd forgotten to put his fully-loaded carousel slide projector into the back seat. It never bothered him, these quirks. He'd laugh at himself. They added to his legend.

I met him on the 4th Avenue sidewalk a few years years ago in front of Capers, and he told me about his newest Metropolitan Vancouver Book project, and that he'd just learned he had not one, not two, but three different cancers. This information was conveyed in the same wry Davis tone as if he were telling me he'd just eaten three Triple-O burgers. But he noted he'd better hurry on this latest mega-project since it was possible the Grim Reaper might be closing the chase.

Don't call him 'Mr. Vancouver'

When I saw him in his New Westminster home in early October last year, shortly after he'd announced to a tearful audience that he'd been given weeks to live, he was dressed in one of his characteristic, well-worn, multi-coloured sweaters, and was, he admitted, feeling the effects of decline. And sadness at the end. Sadness not so much for his approaching death, he told me, as for the 64 book projects he had in his "To-Do" drawer, awaiting future efforts the cancer would prevent. "My life's full of fucking complications," was how he described it. The office where he had been racing to finish his Metropolitan Vancouver Book was piled, as always, to the ceiling with boxes and books and files. But he acknowledged that, to date, his chronological Vancouver history (2,000 Internet pages; 600 projected paper pages) ran from early native occupation of this region up to 1994. But no further. And it was already two years past deadline. The last 16 years in the chronology (to 2010), he said, would have to be done by someone else.

In the weeks prior to his death, numerous newspaper and TV reporters phoned, hundreds of emails arrived, Chuck Davis Day was declared by Vancouver City Council, and he received the George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award -- with a plaque on the Vancouver Public Library plaza. Davis, the author of 11 books on Vancouver, was surprised by this public outpouring of affection, and said to his wife of his impending death: "I should have done this sooner!" It was typical Davis. He was a man without pretension. He hated the idea that anyone call him "Mr. Vancouver." He told me then that he hopes, maybe, there'll be a place in the Vancouver Archives for his enormous collection of historic material -- scores of boxes and 16 file drawers --- that he had gathered on the city. If he had his way, he said, it would be called: "The Chuck Davis Memorial Junk Heap."

And he laughed. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: