One of the least-considered perks of living in British Columbia is some of the cheapest electricity on earth. Only rarely do most of us make the connection between that cheap power and our ongoing violation of free running rivers. Travis Rummel wants us to think again about both.

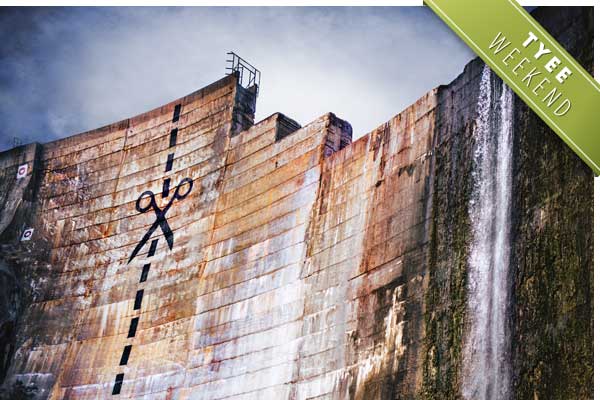

New Jersey-born, Denver-resident Rummel produced and directed DamNation, a documentary that screened Saturday and shows again Thursday at DOXA. Filmed and narrated by American activists committed to dam removal -- and not afraid of a little civil disobedience along the way -- the film is a powerful effort to jolt North Americans out of their complaisant acceptance of big dams as simply "part of the landscape."

Even a dam as vast and imposing as the W.A.C. Bennett Dam on British Columbia's Peace River, the largest in the Commonwealth at the time of its construction, is just "a built thing," Rummel noted, speaking with The Tyee from Maui, where he attended a friend's wedding. "It's not there forever."

DamNation opens on a powerful invocation of this finitude: the ringing voice of former U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt extolling the opening of the Hoover Dam on the Colorado River as "an engineering achievement of the first order," heard over intimate images of a green, mossy gorge where white water rushes from below a mouldering dam wall slated for demolition.

With a vivid cast of genial anti-dam activists, fulminating pro-dam politicians and bureaucrats, and those in the middle -- the clearly conflicted last manager of a hydro-power dam set for demolition; the employee of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the country's pre-eminent dam-building agency, who declares that four of its dams "need to come out" -- the film is nonetheless not "a diatribe against all dams," Rummel insists.

Often visually stunning, the film speaks to a fraught political dialectic. By turns heartbreaking, infuriating and joyous, DamNation weighs the destruction of invaluable natural capital against the perception of control over nature's forces for human advantage.

The devil's due

Making effective use of historical imagery, DamNation recalls the 20th century's enthusiasm for damming rivers to create electric power, to control flooding and to provide water for irrigation. In one delightful sequence it unearths rare footage of a private expedition into the Colorado River's Glen Canyon in the 1960s, just before it was flooded to create Lake Powell. But most of the benefits that dam builders promised, the filmmakers charge, proved either elusive or irrelevant once the barriers were constructed.

What was overlooked in the breathless marketing of dams as engines of economic prosperity and hydrological stability, was their devastating effect on ecosystems and on indigenous cultures finely tuned to those systems' recurring seasons. DamNation, which focuses heavily on the U.S. Pacific Northwest, gives both their due. Almost as much about salmon and steelhead as it is about steel and cement, the film dwells persuasively on the incompatibility of river barriers with the natural cycle of andromadous reproduction that calls such fish back to remote river headwaters to spawn.

In the spirit of giving the devil his due, perhaps, we hear California Republican congressman Tom McClintock condemn the "radical, retrograde ideology [and] bizarre notion that mother Earth needs to be restored." Minutes later, the sorrow is still apparent in the voice of Nez Perce elder Elmer Crow, as he remembers a fishing place culturally central and sacred to his nation, that was drowned behind one of the Columbia's many dams.

If such losses are the tragic depth of the film's story, its moments of redemption come one dam removal at a time. DamNation explores in detail the removal of three dams in Washington State: the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams on the Olympic Peninsula, and the Condit Dam on the White Salmon River, a tributary to the Columbia. To capture the last of those, the filmmakers breach a security perimeter and collect illicit footage of the controlled explosion.

Return of the salmon

What is heartening is how salmon and other wildlife make a startlingly swift return to rivers released from captivity. One member of the Elwha tribe tells a community meeting that we need only to let the rivers go free, and "have the patience and the faith to let mother nature do what she's always done."

If it were only so simple. Of the 1,100 dams that have been removed in the United States, Rummel says, most were obsolete and some unsafe. The major dam removals that his film documents were driven by regulatory demands on dam owners for expensive upgrades, and the less expensive option of removing the dams entirely.

On the one hand, the pace of dam removals is quickening: 53 came down in the United States last year. On the other, there is plenty still to do: some 85,000 dams higher than about a meter remain in the U.S., and as Rummel notes, "while people think of the huge iconic dam, a smaller dam has the same ecological impact."

And while the tide of popular opinion may have swung against both small and large dams, their era is plainly not yet over. The filmmakers draw attention to plans to dam Alaska's wild Susitna River. British Columbians will think of the proposal -- still moving forward -- to place a third dam at 'Site C' on the Peace River, where two existing dams have already devastated the former glory of the Athabasca Delta. Once a verdant nursery for fish, wild birds and beaver, the dams' ecocide is captured, ironically, in a much earlier award-winning documentary: Tom Radford's 1972 Death of a Delta.

The logic of removing old and obsolete barriers to rivers' natural flow is hard to dispute. The filmmakers' long-term vision of restoring all North America's rivers is a more daunting challenge. It's one thing to know the power output of the Condit Dam on the White Salmon River could be replaced by three windmills. It's another to suggest that British Columbia could easily find another renewable source for 86 per cent of our electricity that comes from "hydro" -- that is, from dams.

Perhaps now's as good a time as any to think about it. Rummel points out that the Columbia River Treaty will reopen for new negotiations between British Columbia and the down-river power producers that pay the province $300 million a year to store water behind dams on Canadian stretches of the river. The oldest of those dams is more than half a century old (at 100 years, the Elwha Dam was beyond repair).

"The way the Columbia is being run right now, it's basically just a giant battery," Rummel said. Renegotiating the treaty, he adds, "is a great opportunity for awareness that you could actually effect some change."

Sooner or later, he reminds us, what's built comes back down. And when it does, nature flows more easily.

The DOXA documentary film festival runs until May 11. See here for screenings. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Film, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: