In the past 10 days, North America’s oil and gas industry rattled key geological formations with earthquakes in British Columbia and Texas.

Damage from the U.S. quake, the third largest in Texas’s history, closed a major building in San Antonio and demonstrated that frack-triggered tremors can threaten structures even hundreds of kilometres away from the epicentre.

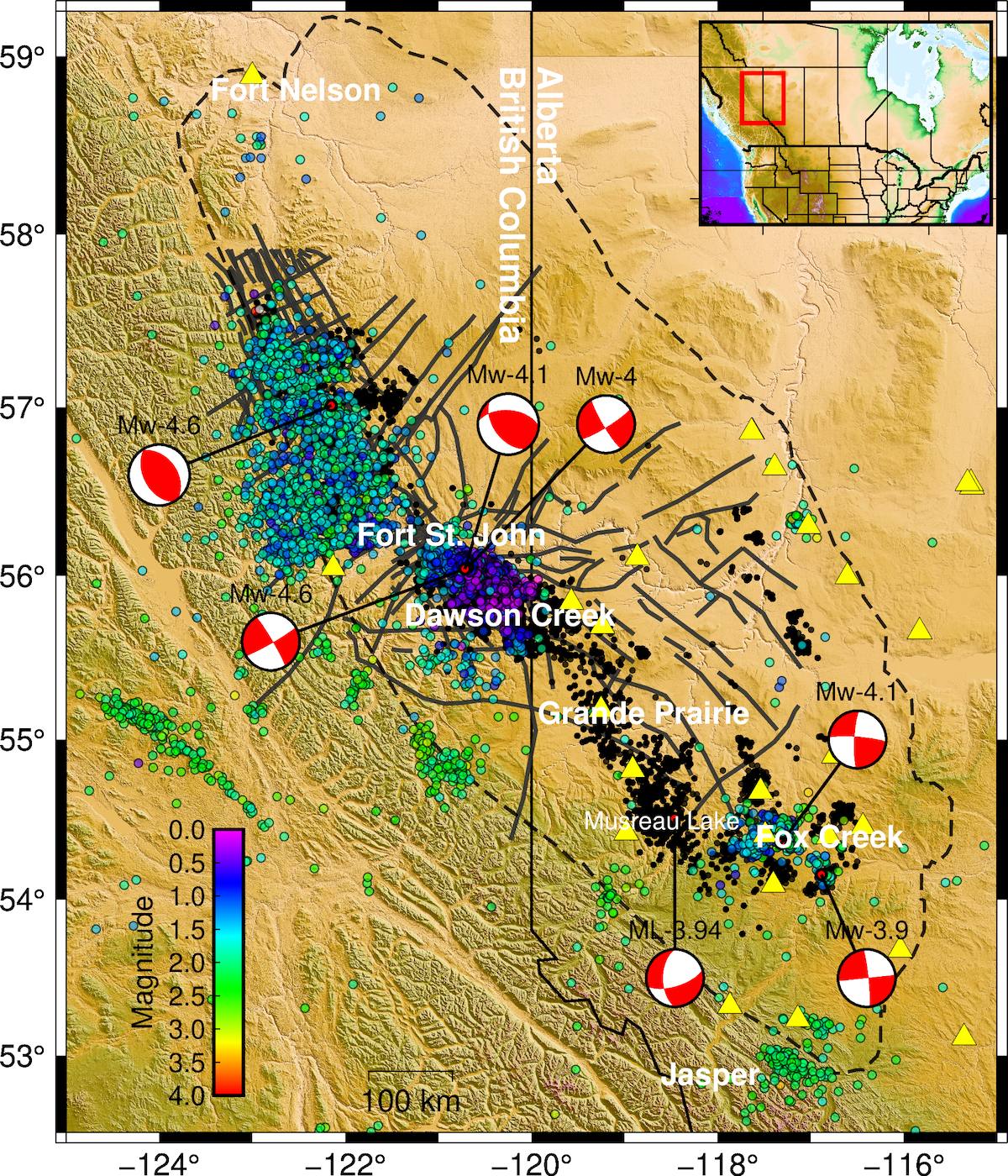

Starting on Nov. 11, Canada’s Montney Formation, a key source of methane and natural gas liquids straddling B.C. and Alberta, experienced three earthquakes measuring over four on the Richter magnitude scale.

Tremors greater than a magnitude of three can be felt while those greater than four can knock items off shelves and in rare cases cause damage to structures.

On Nov. 11 a quake registering 4.7 struck 140 kilometres north of Fort St. John in northeastern B.C. The province’s fracking regulator, the BC Oil and Gas Commission, told The Tyee that drilling by Malaysian-owned Petronas triggered the tremor and a cluster of others. As more earthquakes ensued, the Petronas operation was ordered to shut down but then restarted before again stopping when another quake topping four in magnitude struck on Nov. 15.

Meanwhile the U.S. fracking industry most likely triggered a 5.4 earthquake on Nov. 16 in the prolific oil bearing Permian Basin in west Texas. The largest quake in Texas since 1995, it rumbled the Mexican city of Ciudad Juárez 320 kilometres away. In San Antonio, 560 kilometres from the quake’s epicentre, the structural damage inflicted on a historic, five-storey complex on the city’s University Health campus caused officials to close it down.

After yesterday’s earthquake near Pecos, Texas, structural engineers have determined the Robert B. Green Historical Building downtown is unsafe. This building has been closed off, and a safety zone has been established around it. We will keep you updated on this situation. pic.twitter.com/E9FhETZE55

— University Health (@UnivHealthSA) Nov. 17, 2022

The Railroad Commission of Texas — which regulates Texas's oil and gas industry in a largely hands-off manner — admits that the injection of salty waste water deep into the ground has increased seismicity in the region by putting pressure on nearby faults.

Since 2018 industry’s fracking and wastewater operations in the Permian Basin have caused thousands of earthquakes with a magnitude greater than 2.5.

In the last 15 years, fracking in the Montney Formation has changed the seismic patterns in the region and now accounts for 70 per cent of earthquakes. The industry initiated thousands of small tremors and then progressively triggered tremors of greater magnitude such as the 4.6 quake by Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. that shook the Site C dam under construction in 2018.

How fracking triggers earthquakes

The shale gas industry injects fluids and sand at high pressure into deep and shallow wells to crack open oil and gas deposits trapped in dense rock formations. This fracking creates a network of cracks that can also connect to water zones, other industry well sites and faults.

The reactivation of these faults can then trigger earthquakes, sometimes days after the fracture treatment, scientists say.

Fracking operations also often take the waste water they produce and inject it underground, which can similarly destabilize a geological formation.

For more than a decade the two technologies have created quakes that have damaged infrastructure in fracking zones and even killed citizens in China.

The fact that fracking can trigger tremors tens of kilometres away in unpredictable ways has stymied regulators. Tremors caused by salt water disposal can persist for 12 to 18 months even when the activity has been suspended.

In British Columbia the three quakes caused by Petronas occurred in a remote area near Pink Mountain and there were “no reports of damage” said National Resources Canada on its website.

Under the OGC’s Drilling and Production Regulations companies must shut down their fracking operations when they cause a magnitude four earthquake.

But the Oil and Gas Commission says its seismic monitors recorded different magnitudes than Natural Resources Canada beginning with one measured at 3.75 on Nov. 11 and a level four quake four days later.

The commission told The Tyee that the operator suspended operations of the suspected well after the Nov. 11 event for 24 hours to allow for the built-up energy from fracturing operations to dissipate. But after operations resumed the next day, “a second event was recorded in the evening of Nov. 12 (ML 3.3) and operations on the well of concern were suspended until Nov. 13, 2022,” explained a spokesperson in an email.

When a level 4.03 quake originated in the same area on Nov. 15, fracturing operations were again suspended in keeping with commission rules, the spokesperson said. “The permit holder was required to submit a new operational plan to reduce and/or eliminate further events from the operations. This plan is under review by the Commission,” said the email.

Asked if the regulator was concerned that the same company, Petronas, had also triggered a 4.6 quake in 2015, the spokesperson replied that the commission “is concerned about all induced events.”

‘An issue of paramount concern’

A year ago Allan Chapman, a former senior geologist with the Oil and Gas Commission warned in a scientific paper that stress changes caused by fracking could trigger a magnitude five earthquake or greater in the region, resulting in damage to dams, bridges, pipelines and cities if major regulatory and policy reforms aren’t made soon. “Because a high-magnitude event has a low probability of occurring does not mean it has zero probability of occurring,” Chapman told The Tyee.

“We can look at the billions of dollars of damage in the Abbotsford, Merritt and Princeton areas and the tragic deaths associated with extreme rainfall and flooding in November 2021 to understand the terrible implication of failures of government to address known hazards.”

Chapman added that the province’s experiment in unconventional shale development and large volume hydraulic fracturing “has led northeast B.C. to the sobering distinction of having produced some of the world’s largest fracking-induced earthquakes. It is an issue of paramount concern.”

Fracking appears to have a cumulative effect on geological formations as the technology injects more and more fluid that changes pressure in the formation over time.

Based on Oil and Gas Commission data, fracking triggered 38 earthquakes greater than three on the Richter scale between 2020 and 2022 for an average of 13 a year.

That is an increase compared to the previous seven-year period, during which the industry caused 56 earthquakes measuring greater than three.

This 60 per cent increase, said Chapman, “might be indicative of the cumulative effect of frack fluid injection.”

The fracking industry has had a dramatic impact on geologies, water availability and landscapes wherever it has been allowed. In Patagonia, Argentina, now the scene of intense fracking, the industry has triggered level four and five earthquakes near active wells. Extraction of methane then caused the ground to subside.

In the Permian Basin that includes large parts of Texas and New Mexico, researchers have reported that 68 per cent of earthquakes greater than 1.5 are due to “hydraulic fracturing or the disposal of produced formation water into either shallow or deep geologic formations.” The region is poised to become the earthquake capital of the U.S.

A recent University of Waterloo study assessing the fragility of the Montney Formation noted that some areas are very prone to earthquakes triggered by fracking or wastewater injection, concluding “it appears that most fault planes in the Kiskatinaw area and the northwestern Montney Formation would become unstable with only a moderate change in pore pressure.”

The seismic issues in the vast Montney region, and global examples of the kind of structural damage seen last week in Texas, are at the root of conflicts about where and how fracking operations should be conducted. Chapman is not alone in signalling concern that without more oversight and restraint, fracking may eventually trigger a disastrous earthquake in Western Canada.

TransAlta Corp., the owner of Alberta’s largest hydroelectric dam located south of Edmonton, is currently suing the Alberta government and the Alberta Energy Regulator for granting permits to allow industry to frack five kilometres near its dam.

TransAlta claims in court documents that the Alberta government "has not developed, implemented or enacted any clear policy directives that will protect the Brazeau Storage and Power Development from ‘unacceptable’ risks posed by hydraulic fracturing in close proximity." ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: