If you are youngish, don’t happen to be rich, and want to buy your first home in the Vancouver region, you already know how hard that dream is to achieve. New reports explain just how the deck is stacked against you, and why.

Here are five brutal realities drawn from data by Statistics Canada and a related new report from the BC Notaries Association.

1. First-time homebuyers are getting a lot older.

In Canada, the average age for first time homebuyers is 36 while existing homeowners bought their homes much earlier, on average at 30 years of age. This suggests that for the millennial generation, now in their mid-thirties, acquiring a home takes substantially longer than for previous generations. That’s especially true in Vancouver, where the inflation-adjusted price of the average home has doubled in a decade while wages have stagnated.

2. Almost all young homebuyers must depend on parents’ wealth.

The BC Notaries Association estimates that 90 per cent of all first-time B.C. homebuyers had to get cash from their parents to qualify for mortgages in B.C. The federal government imposed new rules for qualifying for a mortgage in response to national home price inflation and the dangers to the national economy posed by a citizenry heavily burdened by debt.

This has made it even harder to qualify for first home mortgages. Banks now require much more substantial equity contributions from those millennials making average salaries. Which is why nine out of 10 young people wanting to buy their first home have to rely on “the bank of mom and dad” for the down payment.

3. Vancouver has Canada’s widest gap between income and home values, by far.

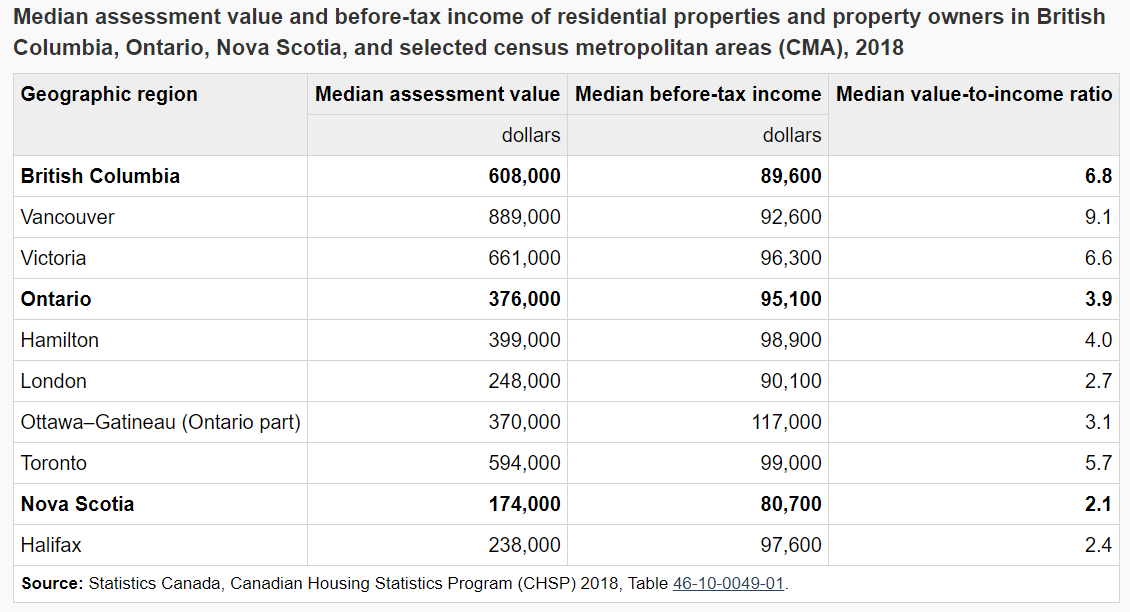

The new Statistics Canada report finds the Vancouver metro region nabs the highest “value-to-income ratio.” This is not a prize you want. The value-to-income ratio is the ratio between the average salaries in a region and the average price of a home.

StatsCan pegs Vancouver area property values at “nine times greater than the income of owners.” The rule of thumb is that ratio should be no more than four. Anything more is considered unaffordable.

The table below shows why Vancouver “wins” this dubious prize. It has the lowest income of any of the listed cities in Canada besides London, Ontario, and the highest average home prices by far.

4. A millennial’s chances of owning a home rise greatly by moving to Toronto.

Given the facts above, Vancouver millennials are better off moving to Toronto, where on average they will make more money and the price-to-income ratio is more than one-third less, at 5.7. (Better still, take that six-figure down payment grant from the bank of mom and dad and buy a house in Nova Scotia, where the median home price is just $174,000.)

5. Renting to save for a home is increasingly a failing strategy.

What happens to Vancouver-area millennials whose parents can’t or won’t provide the financial means to buy a home? Many are consigned to the bottom rung of the equity-building ladder, as they spend their earnings on rent.

An increasingly renter-oriented society might be a good thing if rents were affordable, but they are not. Vancouver market rents are now rising at just under 10 per cent a year, while one in five B.C. renters now hand their landlords over half of their income. In fact, B.C. has the highest proportion of renters in that onerous predicament.

The plight of both millennial renters and owners would be mitigated if governments were to intervene at a scale needed. But that’s not happening.

The province and the feds pat themselves on the back for policies fostering “thousands of affordable units” that won’t even scratch the surface of the problem. The federal government has pledged a $40-billion housing plan that has yet to be funded. If that sounds like a big investment, the portion going to Metro Vancouver would not be enough to lessen housing pressures caused by the fact that land values throughout the region keep climbing, often by hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth in a single year.

There is even a chance the federal investment could have bad unintended consequences, increasing land price inflation by competing for land with the private sector. After all, it is the price of land, not the price of the building, that’s killing affordability in this part of Canada.

The five trends cited here pose a serious threat to the well being of millennials and to the economic and social health of Vancouver and the province. Fortunately, cities have the power to take matters into their own hands in order to reverse our deepening housing crisis.

Municipal governments have the power to tax development, on the one hand, and to use these tax revenues to build non-market housing, on the other. This author previously has provided a set of possible solutions. Perhaps there are others.

Let there be no mistake. To not act decisively is to betray a generation at their peak of entrepreneurial energy and their natural desire to build families and contribute to the future of this place. ![]()

Read more: BC Politics, Housing, Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: