[Editor’s note: The Tyee is pleased to publish the excerpt below from The Sport & Prey of Capitalists: How the Rich are Stealing Canada’s Public Wealth (Dundurn Press), by lauded journalist Linda McQuaig.]

A team of medical researchers at the University of British Columbia spent almost two decades developing the drug Glybera before it was eventually brought to market. Glybera turned out to be remarkably effective — capable in a single dose of treating a rare, deadly genetic disorder known as LPLD, which happens to be particularly prevalent among people living in the area around Saguenay, Quebec.

Yet, in April 2017, for purely business reasons, Glybera was withdrawn from the market and this highly effective drug is no longer available anywhere in the world.

The story of Glybera demonstrates much about what is terribly wrong with today’s pharmaceutical industry, where multinational corporations make life-and-death decisions for reasons that are related exclusively to their profitability.

But it also raises the question of whether the outcome of this sad tale could have been very different — if Canada’s unique, publicly owned pharmaceutical company, Connaught Labs, had remained in operation, rather than being sold off by the Canadian government as part of a wave of privatizations in the 1980s.

Glybera was marketed, by an Italian pharmaceutical company and a Dutch biotech firm, at the price of $1 million for a single dose. This stunning price clearly put it beyond the reach of just about every potential customer and discouraged insurance companies and government agencies from covering it in their programs. But why was Glybera so expensive? Was it derived from some incredibly rare plant or was it particularly costly to produce? No, not at all.

Rather, the extraordinary price was due to purely business considerations — essentially, due to financial calculations made by the companies that marketed it, as CBC-TV correspondent Kelly Crowe revealed in extensive reporting about the drug. An executive from the Dutch biotech firm involved explained to Crowe that the company compared Glybera to other drugs used to treat rare disorders and concluded the $1-million cost was reasonable. “It’s not a crazy price,” the biotech executive said, noting that the $1-million price-tag would be competitive compared to the cost of providing ongoing alternative drug therapies that add up to $300,000 per patient per year.

But, hold it right there. Why are these purely business considerations the only ones being factored in, when we’re dealing with a life-saving drug? The answer, of course, is that business considerations are the only ones that matter in the corporate world. But why is this decision left exclusively to the corporate world — when the drug was originally developed at the expense of Canadian taxpayers? The 18 years of research done by the UBC team in developing Glybera was paid for by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, a government agency that funds basic medical research in Canada.

In fact, it is usually public money that funds the development of a new drug, even in a free enterprise haven like the United States. U.S. economist Mariana Mazzucato points out that most important new drugs — as opposed to copycat variations of existing drugs — are developed in labs funded by the U.S government. “While private pharmaceutical companies justify their exorbitantly high prices by saying they need to cover their R&D costs,” Mazzucato writes in The Entrepreneurial State, “in fact, most of the really ‘innovative’ new drugs, i.e. new molecular entities with priority rating, come from publicly funded laboratories.”

The same is true in Canada, where roughly $1 billion of Canadian public money is spent each year on basic medical research. Yet Canadians have no ownership of the products that result. Instead, the university researchers are permitted to take out patents on the products they develop, and then sell or license those products to corporations that market them, often at great profit. These corporations, as the Glybera case illustrates, can simply decide to stop selling a drug, even if it serves a valid and important medical purpose. Despite our public investment that initiated the whole process, we have no say in the matter.

Still, even in this crazy system, where no recognition is given to the public’s financial contribution, a publicly owned Connaught Labs could well have made a difference. “A version of Connaught Labs might have enabled Glybera to be produced and sold at a lower price,” Dr. Joel Lexchin, the York University health policy expert, said in an interview. “The decision to price it at $1 million was clearly a business decision. As a publicly owned company, Connaught would likely have made a very different pricing decision.”

Furthermore, the UBC team that developed Glybera would almost certainly have been willing to deal with Connaught; they had no financial stake in the drug. “The reason for doing this is to have some impact on patients,” said Dr. Michael Hayden, one of the UBC researchers.

There is every reason to believe then that, if there had still been a publicly owned Connaught, this saga would have a very different ending. Connaught would have undoubtedly gone to great lengths to ensure that Glybera — “a genuine made-in-Canada medical breakthrough” as it has been described — was available for those who needed it, many of whom are Canadians!

In fact, there may be hope for Glybera yet. A new federally funded program run by the National Research Council aims to develop public-sector manufacturing capacity for otherwise extremely costly gene and cell therapies, and Glybera has been selected for possible development. At best, however, clinical trials for a revived version of Glybera would begin in about five years.

On the other hand, if Canada hadn’t sold off Connaught, the miracle drug would likely be available and affordable now.

The privatization of Connaught Labs in the 1980s marked the end of an impressive Canadian public enterprise that had boldly defied the norms of the pharmaceutical industry for decades, by putting human health before corporate profits.

Created before the First World War, Connaught was the vision of a Canadian doctor, John G. FitzGerald, who was appalled by the fact that Canadian children were dying of diphtheria at an alarming rate, even though treatment for the disease was available. The problem was that the $80 price for a full dose of treatments was far beyond the reach of working families, leaving all but the wealthy terrorized by the possibility of a child dying from diphtheria. After carrying out experiments on a horse in a makeshift barn, FitzGerald developed a treatment that could be produced and sold cheaply.

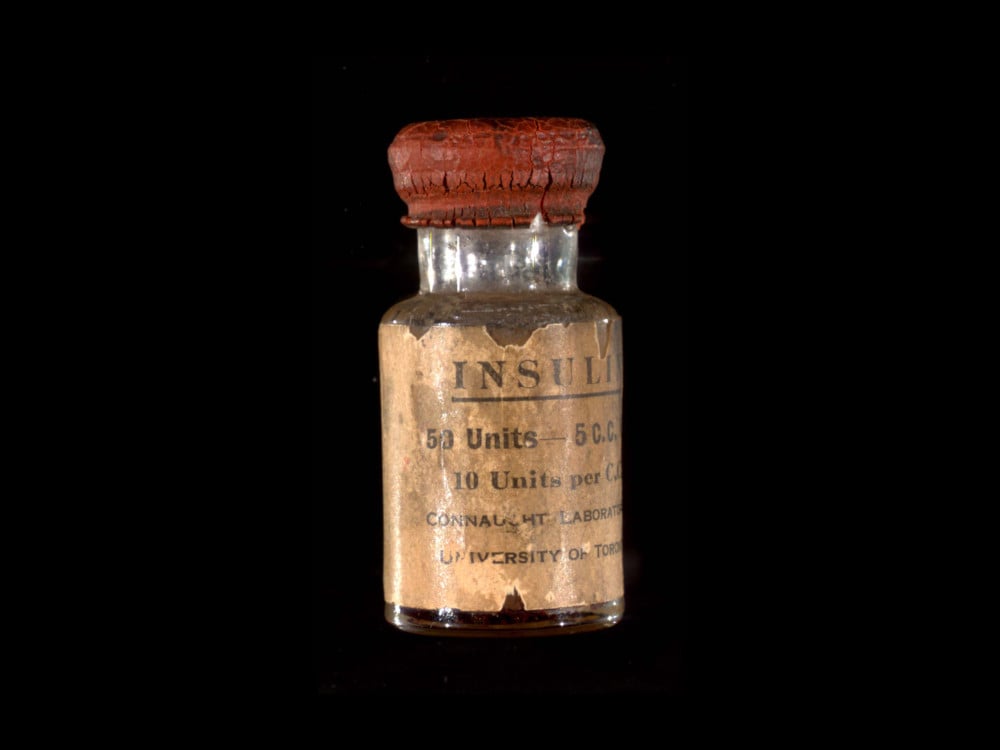

In conjunction with the University of Toronto, FitzGerald created Connaught Labs and made his diphtheria treatment available at low cost to provincial health boards across the country, which provided them to doctors without charge. The minimal profits earned by the lab were ploughed back into research and development, and Connaught went on to develop low-cost treatments and preventative vaccines for other diseases that were killing large numbers of Canadians, including typhoid fever, tetanus, and meningitis. Drug manufacturers and pharmacists objected to having their prices undercut by the upstart enterprise, and Robert Defries, who was involved in the early days of the lab, later recalled that some druggists refused to carry Connaught products.

However, for the following seven decades, Connaught made a significant and unique contribution to Canadian — and international — health care. The multinational drug companies, with far greater resources, spent their research dollars on clinical trials, after the basic research was carried out at public expense. But Connaught carried out basic research, funded partly by government and partly by its own profits. And its research was based on what its scientists considered important, not what promised to be lucrative. It had no sales agents out flogging its products.

And Connaught’s research turned out to be valuable. Its scientists contributed to a number of the key medical breakthroughs of the twentieth century, including the Salk polio vaccine, penicillin and heparin, and Connaught played an essential role in the eradication of smallpox throughout the world.

In the early 1970s, the University of Toronto sold Connaught for $26 million to the Canada Development Corporation, an agency created by Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government to develop and maintain Canadian-controlled companies, in response to public concerns about foreign ownership of the economy. But by 1985, Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government fully privatized Connaught. It has since been absorbed into the global corporate empire of Sanofi, a giant French pharmaceutical company, which is headquartered in Paris.

As a result, we no longer have a publicly owned pharmaceutical company that is a force in global health care — and that could have produced a drug like Glybera, thereby countering some of the serious inadequacies of the international pharmaceutical industry.

To think we had a homegrown public enterprise, one that dazzled and triumphed on the world stage, developing life-saving treatments for the benefit of humanity — in bold contrast to the rapacious pharmaceutical industry — and our political leaders sold it.

Unbelievable! ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: