If we’re ever going to get to a carbon neutral or carbon negative economy, placing a price on carbon is going to be a necessary part of that effort.

With new U.S. government and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports coming out this year warning of extremely expensive and environmentally significant consequences if we fail to act quickly, minor public policy adjustments here and there are no longer an option.

But just because strong action is needed that can be implemented both rapidly and at large scales, it doesn’t follow that the consequences of these actions on people either can or should be ignored.

That’s particularly true when it comes to the working poor and middle class.

As we’ve seen in France and other countries over the past weeks, taxes targeting fossil fuels won’t receive the kind of public support they’re going to need if they’re implemented without sufficient regard for the people paying them.

Fortunately, there is a proven solution that facilitates the carbon dioxide emission reductions that carbon taxes are intended to achieve while also taking into account the burden these taxes impose upon society. Simply make the carbon tax revenue neutral, taking special care to use the money it generates to prioritize tax reductions for the poor, middle class and rural residents affected most.

This is precisely what British Columbia did when it implemented North America’s first carbon tax in 2008. That this tax survived the financial crisis that reached its zenith just two months after its implementation is a testament to the fact that even during the worst of times a skeptical and insecure public can still be persuaded to support a policy if it truly reconciles environmental protection with equity and fairness.

Gradual and revenue neutral

As in the French countryside, residents of rural B.C. often have no choice but to drive long distances on a regular basis. Unlike their fellow citizens in cities like Vancouver and Victoria, public transportation opportunities frequently don’t exist or are insufficient to completely replace the automobile.

When the carbon tax was first imposed in July 2008, it started small. It began at $10 per tonne with incremental annual increases of $5 per tonne scheduled through 2012 until it reached $30. That meant that by July 2012 the cost of gasoline would rise by 6.67 cents per litre. For American readers, that amounts to approximately 27 cents per gallon. To put that in perspective, the gas tax the French government had been planning to impose next month amounted to roughly 25 cents per gallon.

But unlike B.C., France was moving to implement its tax in one fell swoop, and it had no plans to either offset the gasoline tax increase with middle and low-income tax cuts or to use the revenue to provide other significant tangible benefits. As the B.C. experiment with carbon taxes shows, phasing in the tax and making it revenue neutral is crucial to winning public support for any carbon tax that’s going to be significant enough to make a difference.

One study into the effectiveness of the B.C. carbon tax described the steps the then Liberal government took to achieve revenue neutrality this way:

First, the B.C. government lowered the tax rate on the bottom two personal income tax brackets. For a household earning a nominal income of $100,000, the average provincial tax rate was reduced from 8.74 per cent in 2007 to 8.02 per cent in 2008. Two lump-sum transfers were also included to protect low-income and rural households. Low-income households receive quarterly rebates, which, for a family of four, equal approximately $300 per year, and beginning in 2011 northern and rural homeowners received a further benefit of up to $200. Finally, taxes on corporations and small businesses were reduced. Since residents’ tax burden did not increase, the government was able to promote the policy as a “tax shift” rather than a tax increase.

President Emmanuel Macron eliminated France’s wealth tax in 2017 in advance of his proposed gas tax increase, not in concert with it, so it proved impossible to claim that ending that tax was part of an effort to implement some sort of revenue-neutral carbon tax “shift.”

More importantly, however, by putting the wealth tax repeal first and failing to offer low-income and rural households additional tax breaks to offset the impact of the gas tax, Macron signaled his willingness to let the poor and middle class carry most of the burden when it came to taxes on carbon. Had the BC Liberal government followed a similar approach in 2008, I don’t know if cars would have been burning in downtown Vancouver, but they almost certainly would have been trounced in the following year’s election.

Yellow vests, green blindspots

Now, just when we need carbon taxes the most, the ‘yellow vest’ movement threatens to render them a political third rail few politicians will want to touch. Sadly, most environmentalists cheered Macron’s gas tax proposal when they should have jeered, costing them valuable credibility with working-class voters that they're going to need for any successful campaign against climate change.

The phrase “carbon tax” too often triggers a kind of Pavlovian response in the environmental community, regardless of the impact they will have on those paying them. If the environmental policies these times demand are ever going to be implemented on a global scale, then we must abandon the view that sustainability and social justice exist in separate policy silos. People don’t like being treated as a means to an environmental end any more than they appreciate being treated as a means to any other end, nor should they.

Carbon taxes, whether they are revenue neutral or not, will, unfortunately, usually face stiff opposition in the beginning. In B.C., the major opposition party had been in favour of taxing carbon, but it flip-flopped when the opportunity to tag the Liberal Party with the initially unpopular policy presented itself just prior to an election year.

That said, the BC Liberal Party (rather confusingly B.C.’s most conservative major party) was able to retain control of the B.C. government in 2009 in spite of everything. In a March 2016 article on B.C.’s experience with taxing carbon, the New York Times reported that public opposition to the tax had dropped from 47 per cent in 2009 right after implementation to 32 per cent by 2015.

The left of centre BC New Democratic Party has since flip-flopped back to its original support for the carbon tax. With the help of Green Party members elected to the province’s legislative assembly, the NDP took control of the provincial government in May 2017. B.C.’s carbon tax not only again enjoys support across the political spectrum, but is in the process of increasing by $5 a year through 2021. It is scheduled to hit $50 a tonne one year ahead of the federal government’s proposed carbon tax.

That just leaves the question of whether a revenue-neutral approach to carbon taxation can actually reduce carbon emissions. After all, if all the money raised through the tax is ultimately returned to taxpayers in one form or another, where’s the incentive to reduce spending on gasoline, the largest source of CO2 in B.C.?

Well, it has worked. A review of the existing research on the tax’s efficacy published in 2015 in the journal Energy Policy found that up to that point all the studies indicated a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of around nine per cent and that gasoline sales had dropped anywhere between seven per cent and 17 per cent. One study found that commercial demand for natural gas had plunged a whopping 67 per cent since the initiation of the tax (coal is not used to any significant degree in B.C.).

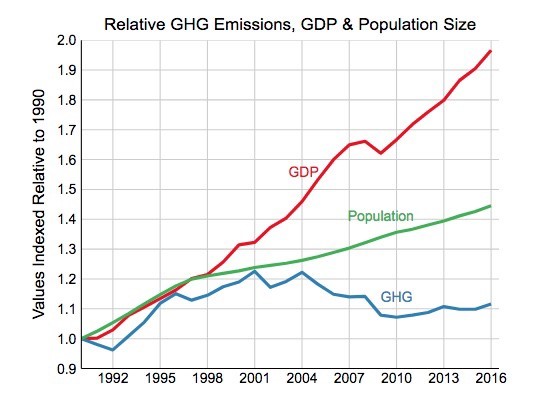

These decreases occurred in spite of the fact the province saw slightly higher annual economic growth than Canada as a whole in the years immediately following the 2008 financial crisis as well as steady population growth.

It’s important to remember that even a revenue-neutral carbon tax can still function as a tax increase for a significant emitter of CO2. The government hasn’t committed to making sure no one pays more in taxes. Only that all the money generated by the tax gets returned to the public in one way or another.

Learn from BC

Under a revenue-neutral carbon tax program, those inclined to use cleaner technologies can reduce their taxes considerably below what others in roughly the same financial boat are paying. A low-income person who decides to purchase a car instead of riding his bike or using mass transit still gets to pocket the quarterly refund payments. But unlike his friends who choose cleaner alternative modes of transportation, his refund payments will go entirely toward offsetting the additional cost of gasoline instead of groceries, rent, or other necessities.

It’s difficult to imagine citizens from the French countryside invading Paris to protest quarterly tax credits or reductions in their income taxes intended to offset a 25¢ per gallon gasoline tax. Even if polls indicated opposition to the new tax, as they did initially in B.C., it’s hard to work yourself up into a lather about it when the government can demonstrate that your overall tax burden hasn’t really changed. And, in all likelihood, what was at first mild opposition or ambivalence would eventually become support once people began to realize the benefits.

The inescapable reality we now face is that whether we tax carbon or not, the cost of emitting so much of it will only be going up from this point forward. Whether it’s coastal buildings washing into the sea or houses built near the edge of a forest burning to the ground, there’s no avoiding climate change’s toll.

A carbon tax that disincentivizes the use of fossil fuels ultimately benefits both the environment and people.

Hopefully, from now on national, regional, and local governments will learn from British Columbia’s example as well as France’s mistakes.

This piece is reprinted from Medium with the author’s permission.

Read more: BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: