On Father's Day in 1951, George Bamberger pitched a no-hitter for the Ottawa Giants. His first child, a daughter, had been born a few hours earlier.

Seven years later, while wearing the red-and-white jersey of the Vancouver Mounties, Bamberger delivered one of baseball's great exhibitions of control pitching. He went 68 and two thirds consecutive innings -- the equivalent of more than seven complete games -- without allowing a walk. His record would last more than four decades.

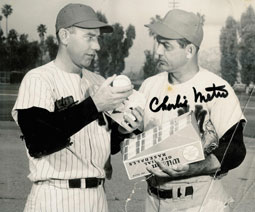

The lean, right-handed pitcher, who died earlier this month, was still with the Mounties when he took part in one of the wackier episodes in baseball history. In a 1962 game in Vancouver, he was outfitted with a radio receiver sewn into an inside pocket of his uniform. It looked like he had a cardboard pack of smokes in his undershirt.

Unseen in the Vancouver dugout, manager Jack McKeon barked commands into a transmitter. The skulduggery failed to catch out any opposing baserunners, although it did bamboozle fans and the first baseman, who took one unexpected pick-off throw in the chest.

Before long, baseball banned the use of radios on the field.

Bamberger was an American-born pitcher who spent eight seasons of his life pitching for teams based in Canada. He first became a coach while still a pitcher with the Mounties in 1960. What he learned here helped him become a longtime major league coach and manager with a reputation for his deft handling of pitchers.

Bamby, as he was called, died in Florida on April 4. His obituary was carried in a handful of Canadian newspapers. The Globe and Mail published three paragraphs and a mug shot. The National Post and Montreal Gazette ran a New York Times obit that failed to mention his stints in Ottawa and Vancouver. The Ottawa Citizen slipped in a sentence about his Father's Day no-hitter. The Province in Vancouver and The Times Colonist in Victoria mentioned he had pitched for the Mounties without offering details. The Vancouver Sun seems to have ignored his passing.

Losing our history

When newspapers pinch pennies by running wire copy and syndicated American features, Canadian readers are denied their history. This is how we lose our stories, one by one, liked runners picked off by a canny pitcher.

For seven seasons, from 1956 to 1962, the Vancouver dailies chronicled Bamby's exploits at Capilano Stadium (now Nat Bailey Stadium). He was a perennial fan favourite, a minor-league star on the Pacific Coast League circuit. Bamberger carried himself like someone who knew he belonged in The Show and had been left behind by an oversight that would surely soon be corrected.

Bamberger was a few years older than Denny Boyd of The Sun, a keen-eyed Boswell who covered the Mounties during the 1958 season. Many years later, Boyd would recall the no-walks streak as one of the greatest accomplishments ever achieved by an athlete based in Vancouver.

"Bamberger was a chesty guy with thinning hair," Boyd wrote in 1980, a nose the size of a wedge of pie and a dimple in which you could catch thrown balls." Boyd dubbed him the Staten Island Stopper, a corny play on his New York home town, where he was born on Aug. 1, 1925. (After his death, a daughter said he had been born in 1923, shaving years from his birth date to not appear over-the-hill as a ball player.)

George was a third baseman with a reputation for a strong throwing arm. He was scouted and signed by the New York Giants, but as he climbed baseball's alphabet-ladder of success, from Class C to Class B to Triple A, Bamberger struggled with control, leading the International League in wild pitches in 1949, repeating the dubious feat in the Pacific Coast League the following season. Bamberger made his major-league debut with the New York Giants on April 19, 1951, during a double-header against Boston. In just two inning, he gave up two walks, four hits and four earned runs in that short span.

The Father's day no-hitter came in a 1-0 victory over the Maple Leafs in Toronto. Not only did he hold Toronto hitless, but Bamberger was responsible for the game's only run, coaxing a bases-loaded walk on four pitches from mound rival Russ Bauers in the top of the second inning. After the game, Bamberger lit a fat cigar, in celebration not of his no-hitter but of the birth of daughter Judy in New York the night before.

Bamby used the spitter

Bamby was one of the original Mounties, moving to Vancouver with the Oakland Oaks franchise for the 1956 season. The pitcher's limited repertoire -- a so-so fastball, a deceptive change-up, a wicked curve that dipped like the new roller-coaster at the PNE -- was enhanced by the occasional use of the spitter, an illegal pitch and a scofflaw's best hope. "We all knew he used it," Boyd recalls, "but we could never get him to admit to throwing the wet one." Later, Bamby would acknowledge he had a special pitch that he called the Staten Island Sinker. It certainly was wet like a sink.

The 1958 streak began on July 10, when he walked a batter in San Diego in the fourth inning. He recorded his 100th PCL victory in his next start, for which the Mounties held a George Bamberger Day on Aug. 1. The club gave him 100 silver dollars. In return, Bamby beat Seattle 6-3, again without walking any batters.

"When you come right down to it, there is no excuse for walking a batter," Bamberger told Boyd back in 1958. "It's accepted as normal, but it isn't normal; it's a mistake. If you throw four bad pitches, you have made four mistakes. There is no other sport where you can survive making that many mistakes."

The streak ended on Aug. 14, when a Phoenix pinch-hitter walked on four pitches. The record would remain unchallenged until last summer, when Nashville's Brian Meadows ran a streak of his own to 70 2/3 innings before being called up to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Bamby's final cup of coffee in the bigs came courtesy of the Baltimore Orioles on April 22, 1959. His entire big-league career involved pitching just 14 and one third innings for two teams over three seasons separated by eight years. He had one save in relief, no decisions, and carries into eternity an inflated earned-run average of 9.42.

Became a brilliant coach

He returned to Vancouver, where the Mounties provided him with a post-graduate education in the art of pitching. After his playing days, he worked his way to the majors as a pitching coach, most notably with the Baltimore Orioles from 1968 to 1977. His 1971 staff was only the second squad in history to have four 20-game winners.

"Bamby to me is the greatest pitching coach who ever lived," former Orioles manager Earl Weaver told the Baltimore Sun shortly before Bamberger's death. "If there was a Hall of Fame for pitching coaches, he should be there without a doubt."

Bamberger later managed the Milwaukee Brewers, pushing Bamby's Bombers to 93 wins in 1978 and 95 wins in 1979. He also handled a woeful edition of the New York Mets, before returning to the Brewers. He retired with a career managerial record of 458-478, settling into a life of painting and putting in North Redington Beach, Fla.

Marlins' Series win rekindled history

I reached him by phone at his home last fall, as his old skipper, Jack McKeon, was guiding the Florida Marlins to baseball's championship. We talked about the radio caper and his days with the Mounties, which he recalled as the happiest in his life. Asked for whom he was cheering, he replied without hesitation: "Jack McKeon. If you can't play for Jack McKeon, you can't play for anybody." McKeon, of course, was the manager who relayed radio signals to Bamby on the mound at what is now Nat Bailey Stadium.

Bamberger, who had cancer and a history of heart trouble, leaves Wilma, his wife of 53 years; three adult daughters, all of whom live in Seminole, Fla.; five grandchildren; three great-grandchildren; a brother in Clearwater, Fla.; and, plenty of good baseball stories from his many days in Vancouver. He was 78. Or 80.

Tom Hawthorn is a Victoria sports reporter more interested in yesterday's stories than today's scores. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: