In a single trip on foot, you can grab a lamb plate from the Parthenon Market, consign your clothes at Turnabout, pick up a bright bouquet from the florist you know and run into a friend walking their dog on Vancouver’s West Broadway. You can get fresh produce, do your banking, grab a fresh sourdough and a box of Punjabi sweets all on Fraser. You can see your doctor, ask cobbler Les Both to resurrect your worn boots and stop for an arepa or flan at Yarina Ramos’s Chevere Eh! on Main before catching your class at Langara College five minutes away.

Whether you call them high streets or main streets, there’s a lot that’s special about these old shopping streets in our cities. You probably have one you visit regularly, with familiar faces like Misti and Gary Mussatto who help you find what you need.

The couple first met on a cruise ship. Misti was a Broadway show dancer from California; Gary was called in as the substitute drummer for their show for one week. Together, they started a family and got into the toy business. They began Toy Jungle on the North Shore and bought The Toybox on West Broadway in 2008, which had been in the neighbourhood since the early 1970s. The stores were written into a children’s book by Gary.

The couple quickly became acquainted with West Broadway’s community.

“There were generations!” said Misti Mussatto. “Many people had shopped the stores on the street for years and years and years. I’d have moms come in and say, ‘I remember those stickers when they were over there in that corner.’”

But streets like West Broadway are changing. As properties are redeveloped on a large scale, the intimate design of street fronts and mom-and-pop businesses is being lost.

The fine-grained street

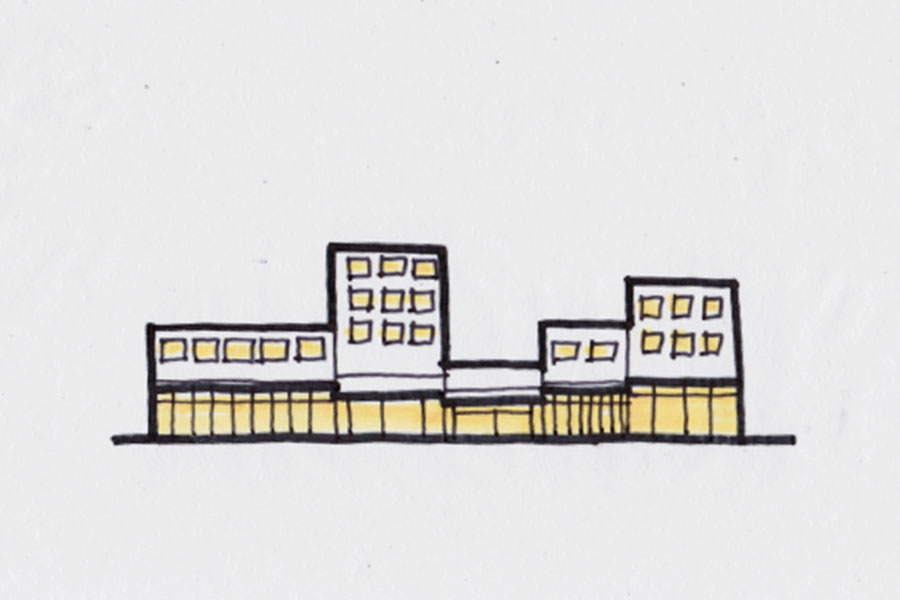

In Vancouver, many main street buildings that house businesses are one or two stories; not very dense for the city’s needs today.

It’s in a developer’s financial interest to assemble a number of adjacent properties on a street and build one large project as opposed to a number of smaller projects. This consolidation helps developers save; they can avoid multiple elevators, stairways, underground parking lots and garbage/recycling rooms. Residential density is added, but commercial density is often lost, and there’s damage to the established urban fabric — especially the human scale of the old storefronts.

Older buildings on main streets are narrow because they’re on small rectangular lots, a legacy of the streetcar era, a time with pedestrian priority before the age of private automobiles and large parking lots.

“Buildings were built smaller and simpler,” said Scot Hein, an urban design professor at the University of British Columbia. “So with a whole bunch of smaller buildings on a street, you get a complex, engaging, vibrant human experience because you’re introduced to something new at the pace of walking. You don’t need a lot of frontage to conduct a business.”

When these properties are bought up and assembled into a single property by developers, residents are added, but there’s a trade-off. Sections of the “fine-grained” street fabric are chopped; instead, the street gets chunkier.

For example, if you were to walk a section of the West Broadway block when the Mussattos moved into The Toybox, you would’ve encountered it and six others stores that sold shoes, lights, curiosities, herbs, coffee and scale models in a total of five small properties. Today, those five properties have been assembled into a single property, now home to two stores — fancy doughnut shop Cartems and a huge Shoppers Drug Mart.

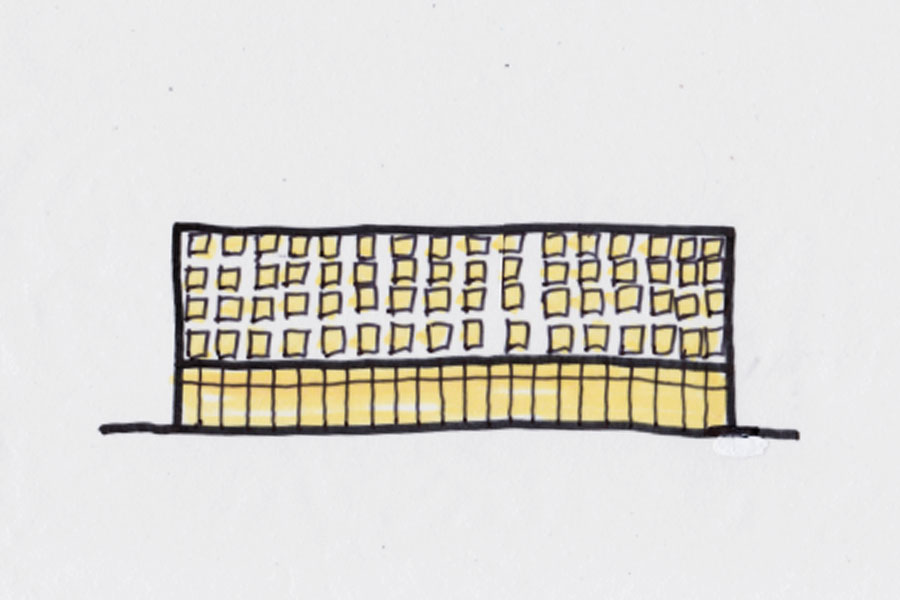

Established tenants — banks, chains, medical offices — often move into the commercial units of a large assembled project. Lenders are more willing to finance developers’ projects if they are familiar with the tenant moving in.

“But big tenants usually turn their backs to the street, so their frontage is insular and muted,” Hein said. For example, offices that move in usually have frosted windows; a stark contrast to what the street likely looked like before with an array of diverse shops you could look into.

This makes the pedestrian experience less interesting (fewer buildings, fewer shops to look at), less interactive (fewer reasons for people to visit a block and, because there are fewer destinations, they’ll glide down a street and have fewer reasons to stop) and less intimate (fewer personalized awnings and flourishes on storefronts).

Land assembly also creates an affordability challenge for small businesses.

Commercial rent in a new building is more expensive than rent in an older building. Newer buildings also tend to have larger commercial units to house the mainstay anchor tenant. More square footage means higher rent.

This means that the kind of mom-and-pops that set up shops and services on main streets — independent barbers, tailors, repair shops, little immigrant eateries — would not likely be able to return post-assembly.

Small biz vs. ‘Broadzilla’

Vancouver’s independent businesses have been sounding the alarm on triple-net leases, in which tenants pay rent, maintenance fees and property taxes. For many landlords in a city with escalating land values, having tenants pay the maintenance and tax burden is the only way they can hang on to their property. If not, they often sell.

The Mussattos of The Toybox were paying a triple-net lease. It became too heavy when their building’s owner decided to redevelop. Taxes jumped and they had to carry that burden. The banks called in the Mussattos’ loans, which they say they could’ve paid if the bank hadn’t acted. “We’ve been paying them and were never behind,” said Misti.

The only way they could save the business was to mortgage their home, which they did, “because we believed in it,” she said.

But because The Toybox’s property was being redeveloped, the Mussattos had to relocate. Before they moved out of the old building, they were paying about $260,000 lease a year for large space of 4,500 square feet. Rent was about the same in their new building, but for about 3,000 square feet.

“What we found after the year and a half that we were closed was that the street had completely changed,” said Misti. “Many businesses had left. Many strong community members had left. They either sold and retired or moved elsewhere.”

But due to the high rent and competition with online shopping — even Toys “R” Us, the world’s largest toy retailer, declared bankruptcy earlier this year — the Toybox closed on Broadway around last Christmas.

Misti doesn’t blame landlords for signing tenants on triple-net leases.

“I’m convinced that today’s independent retailer needs to have a business that either really pops or has really large margins, which is tough.”

Scot Hein at UBC blames this transformation on what he playfully calls “Broadzilla,” the market forces that compel land assembly.

“To go back to the original black and white Godzilla movie, there’s the image of everyone running down the street, looking back as if they’re being chased,” he said. “The market is the market. But it’s putting a lot of pressure on these little properties, so Broadzilla is a metaphor for chasing, trampling and stomping out these precarious little businesses and storefronts.”

The Broadzilla effect is a literal “blockbuster”: city blocks reconfigured as multiple narrow properties are assembled into larger, broader ones.

There’s also the challenge of land value lift from transit investment. The first phase of the Broadway subway, an extension of the region’s SkyTrain due in 2025, will end at Arbutus. There are talks of extending it to UBC, running it beneath the West Broadway shopping strip. Hein worries that this pressure will encourage more land assembly on the street and that the City of Vancouver will facilitate large-scale development because it can use the redevelopment levees it collects through up-zoning to help pay for the city’s share of the transit bill.

“We need to find a different way to generate economic development for transit funding and housing in a way that holds the character and integrity of the street.”

Hein, who was formerly the city’s head urban designer, has a few suggestions to encourage “thoughtful” growth.

No assembly required

“City building takes a village,” Hein said.

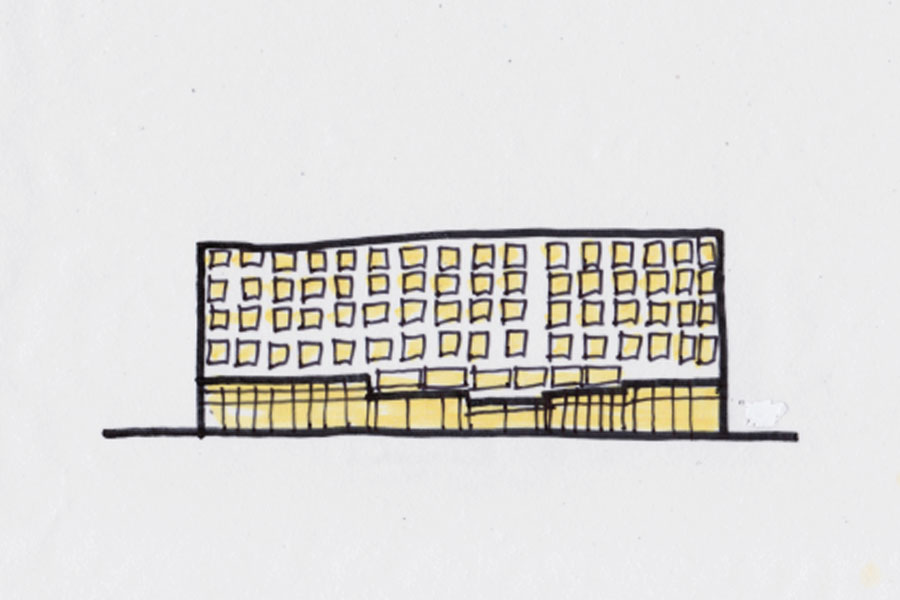

On the development side, companies could help mom-and-pop property owners with redeveloping their own properties.

“There’s a tremendous niche development market here,” he said. “Let’s say mom-and-pop owned a site for many years. They don’t know how to start a conversation about development. Companies, with the leadership of the city, could help them navigate how to put a project together, how to approach city hall, how to approach financing. Also new civic policies could incentivize economic viability for almost 1,400 of these smaller commercial sites across the city.”

It’s similar to how companies like Catalyst Community Developments in Vancouver help religious groups and non-profits redevelop land that they own rather than cashing out because they don’t have the development know-how.

Big property owners like Safeway are redeveloping their properties. Their new stores are built on their old parking lots — right up to the sidewalk — and add housing above.

Mom-and-pop property owners too could realize the potential of their properties and redevelop if they had the help.

Hein says there are lots of potential benefits for property owners and the community. Businesses could return after development. More density means more shoppers and more business. Shop owners could live upstairs from their business. Property owners could encourage extended family to move into the new units.

“This approach to development doesn’t rely on superficial architecture or the idea that bigger is better,” Hein said. “It will help these shopping streets do even better than today.”

Cities could encourage single-lot development (and possibly the inclusion of non-market housing) by offering density bonuses and height where appropriate to the owners of small sites, making it more attractive to develop without land assembly.

Cities could reduce parking requirements. This would be a great financial help because creating parking, especially if it’s underground, is expensive. Shared parking that serves multiple sites could be encouraged.

Cities could reduce permitting times by focusing on basics like weather protection, human scale and storefront vibrancy and less on architectural details.

Hein hopes solutions like these might encourage redevelopment on these streets without losing the human-scale and without displacing the shops, services, people and communities that make them unique.

Critics might dismiss existing buildings as old and unremarkable, but Hein says there’s a lot that can be learned about designing for the future by what exists now; old storefronts stand out in contrast with the new ones.

“Too much attention is paid to the architectural response of the new residential portion for new, large site assemblies and much less to the storefronts that people experience the most. This is one reason why we are losing the character of our local streets,” he said.

Smaller scale development is also more democratic for development because it means little guys can have a hand in city building, too, not just large developers backed with capital and slick marketing.

“This street sells itself,” said Hein last Friday on a walk along West Broadway, pointing to a block which is home to a diversity of businesses like Deacon’s Corner diner, Serano Greek Pastry, Nick’s Barbershop, Ace Cycles and Young Bros Produce. The old Hollywood Theatre is also on this block. “What’s there to market? This is gold.”

Hein continued: “Civic regulations could never legislate complexity, serendipity or even peculiarity. This is about letting everyone be what they want to be, letting the character and expression of the shops continue to evolve in an organic way so that we hold on to what is authentic and memorable about our local shopping streets.”

Read more: Housing, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: