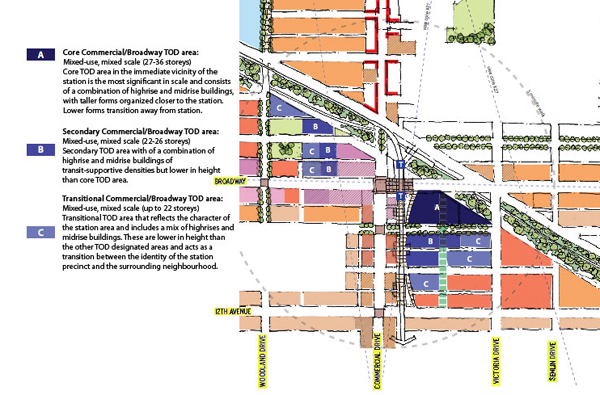

News of the towers rippled through my neighbourhood in early June, at garage sales and block parties, at Micro Footie games and the Trout Lake Farmers Market. The city's freshly minted draft Grandview-Woodland Community Plan calls for a radical remake of the area around the Broadway SkyTrain station: a possible 36-storey building on the Safeway site behind the station, towers up to 22 storeys in "transitional" zones including the area between 11th and 12th avenues near Commercial Drive, and more high-rises up to 26 storeys between Broadway and 7th towards Woodland.

Many people were gobsmacked. "Really?" neighbours would say when I told them. "Really?" An elderly lady leaving Safeway reacted to news of a 36-storey tower with a curt and conversation-ending "They're nuts." Others, such as Morna McLeod, a resident who advised the city on creating an open consultation process for the plan, were more measured. "I was kind of startled," she said of the high-rises at Broadway. "We had talked about greening laneways and gentle densification. It looks like some other office wrote it and it was stuck in."

The Grandview-Woodland proposal has broad implications across Vancouver. It's one of four neighbourhood plans scheduled to be completed by December, and Fairview and Kitsilano are slated to follow in the next two years. City hall's drive for rapid transit along the Broadway corridor to UBC includes big increases in density. As well, while the city is making a concerted effort to engage citizens, it has faced steady criticism for not listening to them.

And so, as a resident who has waited impatiently for 25 years for the city to deliver greater density around the Broadway SkyTrain, I set out to answer a few questions. What do others think of the plan? How did the towers get into it? Are there viable alternative forms of density for our community? Who actually supports the proposed towers? And what are the consequences of all this for the city as a whole?

The neighbourhood opposition to the high-rises is pretty clear. Ian Gill, founder of Ecotrust Canada and a longtime resident of the area around East 6th and Semlin, put it this way in an email: "The proposal for the Broadway-Commercial corner presumably is a joke. If it isn't, then it's going to be the urban equivalent of Enbridge's Northern Gateway. Absurd, totally out of proportion, and ultimately doomed."

A day later, at a Saturday-afternoon block party on East 10th Avenue, just west of Commercial, I met Bev Baker, sitting at a small table with information about the plan and talking to her neighbours. "I'm horrified," she said. Behind her were modest single-family homes, many of them rentals, where the city wants to allow six-storey apartment buildings. Behind that, 12-storey buildings are proposed on Broadway.

At a memorial service last week I spoke to an old friend, Erin Mullan, a savvy working-class and rather Irish-blooded activist who lives in the affordable three-storey rental apartment buildings west of Commercial between the Grandview Cut and East 5th. The proposal would double density in the area. I might best describe her reaction as hyperventilation with steam. In two weeks I've spoken to well over a hundred people (friends, neighbours, people on the street, politicians and planners), but I've found few supporters of the proposed towers -- three at city hall, two area residents and a grocer.

Towers undermine lauded process

Of course, there are many other elements to the plan. Apartment buildings are ubiquitous along east-west arterials. The block that includes the fabulous Waldorf Hotel on Hastings is marked for eight to 15 storeys, the densest portion of major redevelopment on that street between Clark and Victoria. At the northwest corner of Commercial and Venables, a 12- to 15-storey residential building is proposed. Nanaimo would be completely rezoned for townhomes.

Many elements of the "Emerging Directions" are the epitome of good neighbourhood planning. "A lot of what has come out of it is better than we might have expected," said area resident Michael Kluckner, a historian, artist, co-recipient of a 2013 heritage award from the city, and a participant in some community workshops. Putting aside the SkyTrain density, Morna McLeod called it "the most detailed and respectful process I've ever seen."

Of course, the plan protects almost all of the charming, historic two-storey buildings along Commercial Drive between 7th and Venables. Rezoning along Nanaimo would create a more walkable neighbourhood with better services, and there's a strong case for that. Even the proposed mid-rise tower at Venables, which would create social housing and facilities for the Kettle Friendship Society at a transitional intersection on the Drive, deserves careful consideration. There are "pace of change" protections and relocation provisions for existing renters, and a focus on preserving low-income rental in the area north of Hastings known as Cedar Cove. There is extensive discussion of improvements to the public realm, cultural infrastructure and community services.

However, constructive conversations that should emerge from that process are being sidelined by reaction to the dramatic density increases near the SkyTrain. Those proposals also portend change elsewhere along Broadway, as the city tries to persuade senior governments to fund an extension of rapid transit to UBC from Clark Drive.

At the heart of the issue is a concern as big as the towers themselves. Why were towers of this scale never discussed during the half dozen community workshops that were part of a six-month community consultation effort? "It's very disappointing to be honest," said Jak King, president of the Grandview Woodland Area Council and a participant in all six public workshops. "We don't believe the high-rises belong in Grandview-Woodland," said King, who has lived at Adanac and Salsbury since 1991. "Why didn't they put that forward and say, 'What do you think of it?'"

Of course, the planners asked residents if they wanted more density around the SkyTrain station, and most did, but no one really specified the form it would take.

Whose idea is this, anyway?

I asked several city planners who attended a June 6 open house at the Princeton Café on Powell St. -- the last of three open houses in early June to reveal the plan -- where the tower heights came from. "It was a collective decision of the planning department," they said repeatedly. The event felt vaguely like a public flogging, and the carefully worded answer had the faint whiff of something prearranged. I rephrased the question: "Can you introduce me to one person, in the community or at city hall, who thinks towers at these heights are a good idea, and will tell me why they are a good idea?" The preponderant silence that generally followed was a little uncomfortable.

Several people familiar with Vancouver planning told me they believe there's not a lot of support for tall towers along Commercial Drive among city planning staff. So I asked the City of Vancouver's department of corporate communications for an interview with the boss, general manager of planning and development Brian Jackson. He wasn't available in the 48-hour window I proposed.

Instead, I was directed to Matt Shillito, the assistant director of community planning who got such a browbeating at the open houses. He offered a game defense of the development proposed around SkyTrain, and again insisted it was a collective decision. "Existing and future rapid transit development is a major factor," he said. "My view is that it should have some height to mark it as a regionally important transit station." Shillito acknowledged, however, the depth of opposition in the community. "The clear majority of opinion is against these building heights."

Still, I figure accountability should reside at the top. Rapid transit along Broadway is a cornerstone initiative of Mayor Gregor Robertson. Delivering "transit-oriented development" is part of the job description for Jackson, who was hired less than a year ago after the city's falling out with former director of planning Brent Toderian.

So I emailed Jackson, city manager Penny Ballem, the mayor, and his chief of staff, Mike Magee, with a few simple, calculated questions:

• Were these or similar heights proposed by Brian Jackson?

• Were they approved by the city manager or the mayor's office?

• Why are they in the plan when they weren't discussed during the community consultation?

Jackson responded by email, a little obliquely: "All of the emerging plan directions were developed collectively by staff in the planning department and other city departments." He added that the tower heights proposed reflect "longstanding city policies" and documents such as Greenest City 2020, Transportation 2040, and Translink's 2006 Transit Village Plan.

"However," he added, "we understand that tower heights are a major concern for many in the neighbourhood and would like to pursue different built forms to both achieve the density objectives and respond to those concerns."

Policies don't support towers

How much ground the city might give is an open question. Former COPE city councillor and onetime mayoral candidate David Cadman, who lives on McSpadden Avenue near Commercial Drive and 4th, thinks some people at city hall may have had an outcome in mind from the beginning. "I suspect this is an over-ask, a big reaction, and a reduction by a third," he said.

Me, I wanted to know more about those longstanding city policies, so I read the documents Jackson referred to. Remarkably, the Transit Village Plan indicates that the area already meets the study's minimum-density definition of transit-oriented development, and if it were built out based on existing zoning it would substantially exceed that threshold.

So I emailed the senior quartet again, explaining that the two big-picture reports call for density around transit stations but say nothing about the degree, form or height. I also noted that the Transit Village Plan calls for three towers ranging from 18 to 24 storeys on the Safeway site. "Am I missing anything?" I got a call from the mayor's office to defend his honour, and then Jackson phoned to allow that my interpretation of the reports was correct.

That night, I met with Councillor Andrea Reimer at Bandidas Taqueria, across Commercial from the proposed site of a 22-storey tower, for the first of two conversations. Reimer is not a fan of the towers. "We seem to have only one way of expressing density, but we know from around the world that's not the only way." She said a public event to look at alternative forms of density would take place "as soon as humanly possible."

As the councillor responsible for Grandview Woodlands and chair of the standing committee on planning, transportation and the environment, Reimer said she was briefed on the draft plan on June 3, two days after the first open house. She added that the planning process is "a black box" for council. "We hear nothing until we see a written report. At that point, the only intervention is yes or no."

'Freewheeling' process fails neighbourhoods

The forces that drive the development of towers are formidable. High among them are the city's transit ambitions. Patrick Condon, senior researcher at UBC's Design Centre for Sustainability, says the City of Vancouver was built around a streetcar system, which shaped the form and texture of our neighbourhoods. Condon argues light rail and buses respect that texture, while the nodes of density and height driven by rapid transit undermine it.

With the Canada Line down Cambie and now the plan for a subway along Broadway, Vancouver politicians have made the second choice. Condon points to the February 2013 KPMG report The UBC-Broadway Corridor: Unlocking the Economic Potential, prepared for UBC and the City of Vancouver to illuminate the scale of the city's ambition. The report, which makes the case for a subway, says the corridor including UBC is currently home to 104,000 people and 95,000 jobs but predicts those numbers could grow by 150,000 in the next 30 years. By way of comparison, in 2009, Metro Vancouver pegged population growth alone over 35 years for all of Vancouver and UBC (which is a separate electoral area) at just 157,000.

However, while the KPMG report looks at the prospect of major redevelopment on the federally owned Jericho lands west of Alma, and on aboriginal land in Kitsilano around the Burrard Bridge, it respectfully leaves Commercial Drive out of the picture. The City of Vancouver, apparently, not so much.

Another factor driving the proposal for towers on Commercial is simply the habits we've developed as a city. The low-rise streetwall topped by slender towers -- the podium-point tower -- has become the standard at rapid transit stations all over the Lower Mainland, and the internationally lauded vernacular of Vancouverism thanks to the North Shore of False Creek. The question is, should we replicate that vernacular around transit stations along the Broadway corridor?

For Kira Gerwing, a former Vancouver planner who contributed to the city's Chinatown plan and now works with the Vancity Credit Union, the development community's planning habits are not sufficiently adaptable. "They know how to approve a tower and podium. They now how to build it, they know how to finance it," she says, adding that you don't need tall towers to deliver density. "There isn't a lot of mid-rise, but in fact, that's the best form of development for neighbourhoods that are willing and able to receive additional density."

Density doesn't need height

Condon also argues that the density the city wants around Broadway and Commercial can be achieved without much in the way of towers at all. "I think the city and developers feel it's easier to do one tower project than many incremental projects. That's tragic, and to the extent that it's true it seems to be foreclosing a much less expensive and neighbourhood-friendly form of development."

We do have other models in the city. Condon and Gerwing, who lives at 7th Avenue and Commercial, are both fans of Arbutus Walk, which accommodates about 1,000 residences in about three blocks of real estate west of Arbutus along 12th Avenue. Then there are the mid-rise towers in Chinatown. And while the development of Cambie has generated its share of controversy (the Marine Gateway development, peaks at the equivalent of 35 storeys and a 45-storey tower is the tallest of 13 planned for the 28-acre Oakridge site), the Cambie plan calls for low- and mid-rise buildings elsewhere.

In an interview with the online magazine Spacing last year, former director of planning Brent Toderian put it this way: "Our development industry, and even the marketplace, has come to expect that densification will mean towers with views." He said mid-rise projects can be more sustainable and affordable, are more acceptable to the public, and are capable of delivering the density that towers create. "If we can provide clarity on where towers will be, and by definition where they won't be, that helps with our entire discourse on densification in the city." And while he allowed that towers might be considered at key intersections, including transit stations, he noted that in the Norquay neighbourhood on Kingsway that has meant one tower of just 22 storeys.

The economics of tall towers, however, drive developers to keep pushing them. Views are a valuable commodity, and towers can be hugely profitable once they rise above 20 storeys. Developers can presell towers much more easily than low- and mid-rise buildings, which means less capital and more profit. Developers also find residential much more lucrative than mixed use, and so in an area like Commercial and Broadway, where the city wants more jobs as well as residents, a big residential component makes the site more attractive.

For the City of Vancouver, which has lagged other municipalities in creating density around its rapid transit stations, there is another issue. Rapid transit has created competition between municipalities for jobs and homes, and for development fees and tax revenue. Burnaby will now allow 70-storey buildings in the Brentwood neighbourhood. Some expect Metrotown will grow by 30,000 residents in the next 20 years.

Who shapes the conversation?

The stakes create a huge imbalance when it comes to community input. So does the structure of the conversation. Did the form or density of development on the key Safeway site come up much in the community consultation? Well, no. How specific has the city's conversation been with Safeway and its agents? Keep in mind here that with this month's purchase of Safeway by Sobey's, it became part of a company with $25 billion in annual sales, and it's linked to a large real-estate trust. Safeway owns three more key underdeveloped sites along the Broadway corridor. Have Safeway's people talked to the city's people? Of course they have. How specific has the city's conversation been with individual developers? "We get calls from a lot of developers interested in buying that property!" Jackson said in a brief email, when I asked him about one prospective purchaser.

Ian Gillespie, the developer of the Woodward's project and the Oakridge site with architect Gregory Henriquez, spoke in January to a San Francisco audience about how he's dealt with Vancouver's senior planners in the past. According to Easy as Pie, a participant in the online SkyscraperPage Forum, he described it as freewheeling: "Gillespie said that he'd never once built a project in Vancouver that fit within existing zoning -- a huge laugh line for the SF audience -- and he described a somewhat astonishing development process for the Shangri-La, which basically consisted of a few lunches to get height and lot coverage settled before even acquiring the land."

Only then, wrote Pie, did Gillespie finish a co-venture deal with the property owner "on the back of 'a Tim Hortons napkin'... There were also plenty of other stories that reinforce the 'discretionary' nature of discretionary planning in Vancouver, but none so powerful as Gillespie's flat-out admission that you get what you want as long as you buy the city off with daycare space or whatever they want."

Gillespie is in some ways a special case, given his creatively daring and civic-minded outlook, and where he gets a yes from planners many others get a flat-out no. But his remarks -- and I offered him the opportunity to dispute them -- really do point up how one-sided the conversation can be. Whether or not this story is a fair account, it feeds increasingly pervasive cynicism regarding the relationship between developers and city hall. Is it too cynical by a third, or should the cynicism be scaled back by 90 per cent?

The city gets its cut

Gillespie's observations point to another factor that drives the city to favour towers. When there's more money on the table, the city can leverage more amenities for the residents, from daycare space to arts venues to affordable rental housing. You could argue that Vancouver does this very well, and you can argue that we've become dependent.

Grandview-Woodlands got a preview of its future this earlier this year with the controversy at Main and Kingsway. Everyone seems to be smarting over city hall's approval of the$150 million, 19-storey Rize Alliance development, which was scaled down from 26 storeys. The city got $4.5 million for arts groups and $1.75 million for affordable housing from the developer, but Caitlin Jones, executive director of the area's Western Front arts facility told CBC Radio they are less interested in the money than they are concerned about the negative ripple effect of development pressure on existing venues. "If you make it desirable for condo developers to move in, you are going to lose the artists that made you what you are." Meanwhile, others complained that the height reduction cost the community 42 rental units.

Many people, such as Julia Dykstra, another advisor to the city on the Grandview Woodland planning process, believe the sort of density provided by towers around Broadway and Commercial are their best shot at being able to afford home ownership in Vancouver. Others insist that economical housing and community benefits can be achieved without towers.

Critics believe the pace and scale of change proposed around Broadway would fundamentally change the character of the whole neighbourhood. David Cadman, whose last term on council ended in 2011, believes changing demographics and rising commercial rents would force out many of the mom-and-pop businesses that give the Drive its charm. "The effects on the neighbourhood would be profound."

Michael Kluckner, who calls the podium-tower "a vertical gated community," argues that a huge increase in density would only worsen congestion at the SkyTrain station, notwithstanding improvements planned for 2016."I don't see that Broadway and Commercial is going to be anything other than a transit hub if they build it the way they propose."

Kluckner adds that certain types of density have become "kind of religious... particularly when you can greenwash it." While only a very few would challenge the city's key goal to cut car use and encourage other forms of transportation to create a livable city and protect the environment, there are many ways to do that. Patrick Condon argues that we need more adaptable and resilient building forms than the podium-tower, and that wood-frame construction has less environmental impact than concrete.

Ray Spaxman, who was the city's director of planning from 1973 to '89 and is a member of the Downtown Eastside Local Area Plan Committee, has argued vigorously that the city has not given careful enough consideration to the impact of new residential towers in that neighbourhood. While the impact of major redevelopment on lower-income residents around the Broadway SkyTrain station may be less acute, the ripple effects are still a significant issue, and he feels that in its quest for density the city is losing its focus. "Revenue generation and high density have become the new mantra. Quality of life should be the mantra."

City scrambles to save the process

These are issues with so many moving parts, it's important to create a structure that provides for balanced conversation. Brent Toderian declined to speak to the specifics of the Commercial and Broadway proposal. He said he wasn't familiar with all the details. But he did say that good planning is a design exercise and a community engagement exercise where the two educate each other. "The key is the process."

Andrea Reimer, who has made transparency and process hallmarks of her two terms on council, feels what's happened in Grandview-Woodland "is not outside of the current process." But, she says, "I think there are some grave deficiencies in the process, and they need to be fixed." She wonders whether the firewall between planning and council is an asset or an impediment. "The community's representatives are the elected officials."

In the meantime, the city is scrambling to recover a community planning process that has gone completely sideways. Flyers inviting residents to a July 6 forum on building forms in the Broadway SkyTrain area were distributed on the weekend, even though the city hasn't yet chosen a venue. The final draft of the Grandview Woodland plan is due in September. Reimer believes it's not critical that the plan be approved by December, but it would have a ripple effect for the Kitsilano and Fairview planning processes due to begin early next year.

There are bigger questions, though, than what the city might allow at Broadway and Commercial. There is a process with "grave deficiencies." There is a transit plan that, so far at least, seems to presuppose the result of community planning in historic neighbourhoods along Broadway. Perhaps it's time for city hall to make it very clear that they will not push high-rises on communities that do not want them. Perhaps it's time to demonstrate that, when there's real money in the game, citizens are still in charge.

To submit online comments to the city on the Grandview-Woodland plan click on Share Your Views on the plan's home page. The current deadline is July 3. Exploring Options for the Future of Broadway and Commercial will take place Saturday, July 6 from 10 am to 2 pm. The city says space is extremely limited. To register, click here. The Grandview Woodland Area Council meets to discuss the plan on Tuesday, July 8, at 1655 William. Visit their website here for more details. On Tuesday, July 2, from 5 to 7:30, the Kettle Friendship Centre and Boffo Properties will have an open house at 1725 on the redevelopment of the Astorino's banquet hall site at Commercial and Venables. ![]()

Read more: Transportation, BC Politics, Housing, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: