An advocacy group trying to increase the number of highly skilled resident doctors who can apply to work in British Columbia says it’s “two down, three to go” when it comes to hitting its goal.

The Society of Canadians Studying Medicine Abroad has been in court for the last six years, arguing that anyone who studies medicine overseas should get the same crack at domestic residency positions as graduates from Canadian and American medical schools.

“If an immigrant physician is the best match for the position, then the immigrant physician should be hired for that position,” Rosemary Pawliuk, president of SoCaSMA, told The Tyee.

Earlier this month the Supreme Court of BC ruled that two of the five parties named in SoCaSMA’s original petition to the court did not have authority to say students from Canadian and American medical schools get priority over international medical graduates. The two parties, the Canadian Resident Matching Service and the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada, were then dropped from the petition.

Pawliuk says next she hopes the courts will rule the remaining three parties also do not have the authority to prioritize Canadian and American graduates.

Those parties are the province’s Health Ministry, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of BC, and the University of British Columbia (currently the province’s only operational medical school).

Astha Burande, director of education for the Canadian Federation of Medical Students, told The Tyee there are benefits to prioritizing locally trained doctors for residency positions.

Canadian graduates, who have committed enormous amounts of time, energy and finances to learning and studying the Canadian system, should be prioritized for jobs here, she says.

“If we put all medical students in Canada through the training for this system, get them to pay for school here and learn here but don’t help them get into a job here then that’s not fair,” Burande says, adding that residency placements are highly competitive.

To get into medical school you first need an undergraduate degree and many prospective applicants go on to get a masters or doctorate to get a competitive edge, Burande says. Applying for a single school can cost hundreds of dollars, and it’s common for medical students to apply for several years to multiple schools before they get accepted. There is no limit on how many times a student can apply for medical school.

Then there’s the cost of medical school, which she estimates ranges from $20,000 to $40,000 per year.

Canadian medical schools teach students about the Canadian public health system, including which drugs are available and subsidized through public health, about Indigenous health, LGBTQ2SIA+ health and other social determinants of health in a Canadian context, Burande says.

It’s rare for Canadian graduates to apply for residencies outside of Canada because this is the system they were trained for, she adds.

Canadian medical graduates vs. international medical graduates

There are four steps to becoming a doctor in B.C. First, you graduate from a medical school that is recognized by the World Health Organization. Second, you get some post-graduate training in the form of a residency. Third is taking an exam set by either the College of Family Physicians of Canada or the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. The final step is to apply to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of BC to be licensed provincially.

Medical students applying for Canadian residencies are organized into two streams.

The first stream is for graduates of Canadian or U.S. medical schools.

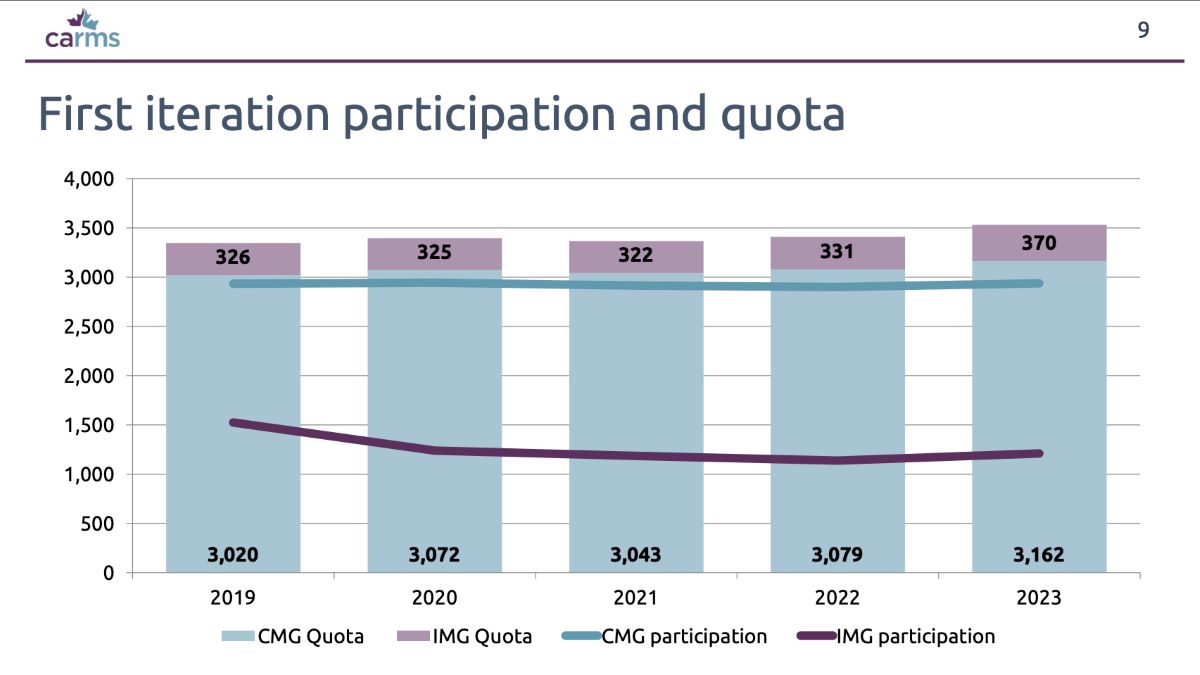

The Canadian Resident Matching Service says in 2023 there were 2,992 Canadian medical graduates and 22 U.S. medical graduates who went through the entire resident application process.

In 2023 there were 37 specialties they could apply for a residency in, which jumps closer to 70 when you include sub specialties, Pawliuk said.

For UBC graduates, 270 of the eligible 286 students with no prior postgraduate training were placed in residencies in 2023.

More than 95 per cent of Canadian medical graduates and 77 per cent of U.S. medical graduates who applied for residencies were placed in a Canadian residency program.

International medical students account for all medical schools outside of Canada and the U.S. In 2023 there were 1,550 international medical students applying for residencies.

Pawliuk says international graduates can only apply for residencies in family medicine, internal medicine, paediatrics and psychiatry through UBC.

These are general positions that pay less than other specialties, Pawliuk says. Highly qualified doctors are discouraged from coming and practicing in Canada because they are forced into an area that may be outside of their specialty or interest, she adds.

International graduates are much less likely to get placed in a residency.

Data from the Canadian Resident Matching Service shows just over 35 per cent of international medical graduates who applied for a residency got one in 2023.

All international medical graduates who do residencies in Canada are required to sign a Return of Service contract, which places them in an “underserved” area of B.C. for at least two years.

Pawliuk says limiting which specialities international graduates can apply to and controlling where they work is a form of discrimination. A researcher who volunteers with SoCaSMA published a paper about this discrimination in the Canadian Medical Education Journal in 2021.

The Tyee contacted the Ministry of Health to ask why it maintained the two-stream system and to respond to the allegation of discrimination. The ministry said it was unable to comment as the matter is currently in litigation.

The rules limit how Canadians who went to medical school overseas can practice, Pawliuk says.

There are many reasons a student might want to study internationally, she adds. A student from a poorer background may have to work to support themselves or their family and may not have the ability to meet the volunteering requirements to get into a Canadian school. Or a student may be funded by their community and need to head overseas to get a more affordable education with the goal of returning to work as a doctor in their community. Other students are first- or second-generation Canadians and want to reconnect with their culture or live with family overseas while going to school.

The two-stream system is not about qualified or less qualified applicants because all medical graduates have to pass the same exams to practise here, Pawliuk says.

Instead, she says, the two-stream system was created in the early ’90s as a means to save on health-care costs.

A 1991 report for the newly elected BC NDP government encouraged the province to save money by: limiting the number of doctors in B.C.; “[encouraging] Canadian graduates to train in fields in which there are shortages”; prohibiting “immigrant physicians” from practising in B.C.; and limiting positions for graduates of foreign medical schools.

This led the province to prohibit international medical graduates from applying for residencies in B.C., Pawliuk says. This changed in 2006 when the province created the two-stream system and allowed international graduates to apply for residency programs. International graduates were only allowed to apply for around 10 per cent of the specialties Canadian and American graduates were, she adds.

CBC reporting from 2022 connected the 1991 report with the province’s current shortage of family doctors.

Pawliuk is a retired lawyer and has been president of SoCaSMA since 2013. She says she first learned about B.C.’s two stream system when her daughter, a Canadian who had turned down opportunities to study in the U.S. for a chance to study neurosurgery in Cork, Ireland, was told she couldn’t apply for a domestic general surgery residency.

Pawliuk says she told her daughter, “Honey, that’s not legal.”

B.C. previously tried to control how many doctors practise in B.C. and where they work. Court cases in 1985 and 1988 ruled the province didn’t have this authority.

Pawliuk links the province’s 2006 decision about a two-stream system to this history. It’s easier to control international medical graduates, who have less ability to advocate for themselves and push back against this discrimination, she says.

SoCaSMA’s petition argues all medical students should be able to compete for jobs on individual merit, similar to how other professional industries, like law, engineering and architecture do, Pawliuk says.

These professions similarly require schooling and post-graduate training where they work under the supervision of a licensed professional for a set amount of time before writing their own licensing exam “and are allowed to fly solo,” she says.

Brian Samuels, a lawyer with the honorary title of King’s Counsel who is representing SoCaSMA in court, told The Tyee if they win, the court could say a different system has to be created to match graduates with residencies, but likely won’t say what kind of system has to be created.

This might mean that some local graduates don’t get jobs, he says, adding the entire licensing regime is governed by the Health Professions Act “which says everything has to be done in the public interest, not in the interest of local graduates.”

If the province was worried about local graduates not getting residencies it could always fund more residencies, Samuels adds.

Specifically, the number of residency positions available to international graduates, Pawliuk says, adding that the B.C. government keeps adding residency spaces to the Canadian medical graduate stream, which already has more positions that participants.

Pawliuk says physicians should get jobs based on their merit and that an education doesn’t guarantee a graduate a job.

“Just because you graduated from UBC with a bachelor of science does not mean you’re entitled to get into medical school and just because you graduated medical school does not mean you’re entitled to work as a physician,” she says.

The Tyee also reached out to several organizations to ask what the benefits of the two-stream system for residencies are. The Medical Council of Canada, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of BC and the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada all declined comment. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: