An investigation by human rights organization Amnesty International has found that Coastal GasLink, its private security firm, the RCMP and Canadian and B.C. governments all violated the Indigenous rights of Wet’suwet’en who oppose the pipeline project.

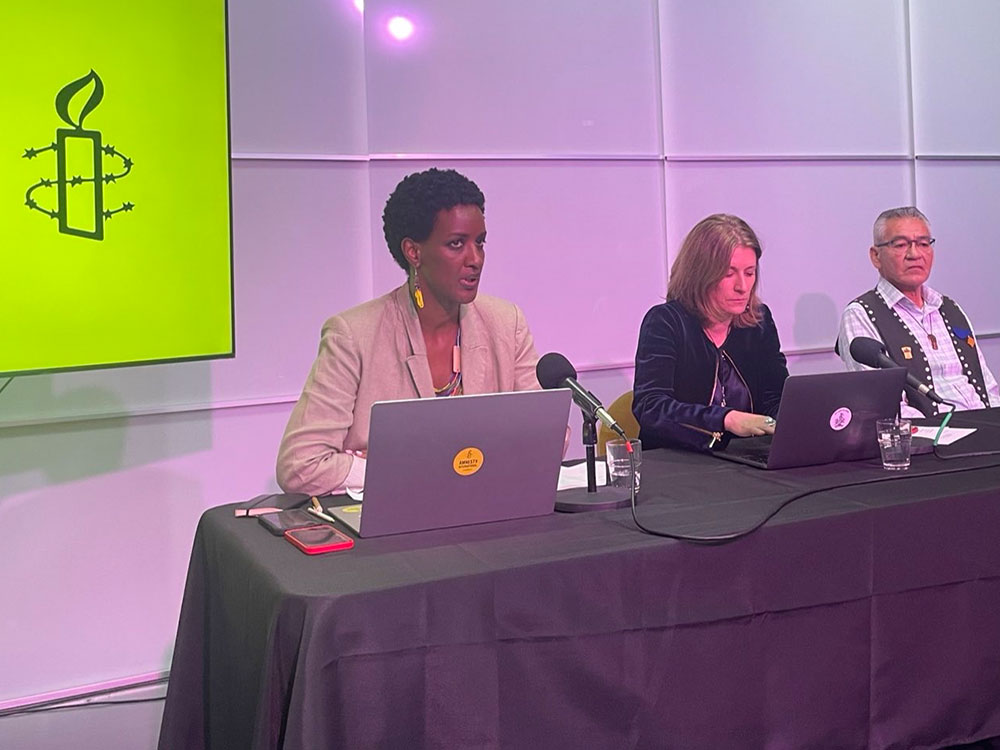

“What emerges clearly from our report is that the intimidation, the harassment, the unlawful surveillance and the criminalization of Wet’suwet’en land defenders were part of a concerted effort to remove them from their ancestral territory in order to allow the pipeline construction to proceed,” Ketty Nivyabandi, secretary general of Amnesty International Canada’s English-speaking section, said at a news conference Monday.

Amnesty’s researchers were also surveilled while conducting its investigation on Wet’suwet’en territory, according to France-Isabelle Langlois, executive director for the organization’s francophone section.

“Indigenous Peoples are entitled to give or withhold their consent to project proposals that affect them,” Langlois said. “The Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs, on behalf of the clans, have consistently withheld consent for the Coastal GasLink pipeline project. Nevertheless, construction of the pipeline has proceeded without their free, prior and informed consent.”

The 94-page report, "Criminalization, Intimidation and Harassment of Wet’suwet’en Land Defenders," outlines how the pipeline company failed to properly consult Wet’suwet’en hereditary leaders and then obtained a civil court injunction to remove those who blocked access to the pipeline route.

Wet’suwet’en hereditary leaders have voiced opposition to pipelines through the territory since before the Coastal GasLink project was proposed.

The RCMP’s Community-Industry Response Group, which was formed in 2017 to address opposition to pipelines and other natural resource projects, has undertaken several high-profile police actions on Wet’suwet’en territory under the injunction.

Dozens of people have been arrested over the past five years, several of whom await trial on criminal contempt charges.

Amnesty’s report comes 26 years after a Supreme Court of Canada decision affirmed that the Wet’suwet’en and neighbouring Gitxsan Nation had not relinquished title to their traditional territories, which together cover 58,000 square kilometres in northwest B.C. The successful appeal decision, known as Delgamuukw-Gisday’wa for the Hereditary Chiefs who fought the court case, came Dec. 11, 1997.

“Twenty-six years after this landmark decision, our research findings reveal that the Wet’suwet’en Nation continues to suffer severe violations of its internationally recognized rights,” Nivyabandi said, including the right to self-governance, the right to free, prior and informed consent and the right to make decisions related to its territory and its resources.

She added that the violations should be considered together with “centuries of Canadian government policies aimed at removing Indigenous people from their ancestral territories.”

Nivyabandi cited examples, including forced evictions, Indian residential schools, mass incarceration, forced sterilizations and the child welfare system.

For its investigation, Amnesty interviewed 22 Wet’suwet’en land defenders, five other Indigenous land defenders and one non-Indigenous person, Nivyabandi said. It also reviewed court documents, UN reports, government publications and a “wide range of documentary evidence,” she added.

Amnesty also reached out to “various government officials” and other parties during its investigation, including Coastal GasLink, and offered the chance to reply to its findings, Nivyabandi said.

“Unfortunately, what we have heard does not begin to answer or to address the recommendations that we have made,” she said.

The report’s findings fall under three main categories: insufficient consultation on the Coastal GasLink pipeline project; the “overbroad” scope of the court injunction; and “serious human rights violations and abuses” by the RCMP’s Community-Industry Response Group and Coastal GasLink’s private security firm, Forsythe Security.

Canada’s police watchdog, the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission, announced earlier this year that it would undertake an investigation into C-IRG after receiving hundreds of misconduct complaints. Last month, the complaints commission said the investigation had been delayed as the RCMP had not provided records needed to complete it.

Nivyabandi said Amnesty’s investigators had found violations by RCMP and Forsythe that included intimidation, harassment and unlawful surveillance of Wet’suwet’en members. She added that police used disproportionate force and had arbitrarily arrested land defenders “solely for exercising their Indigenous rights and right to freedom of peaceful assembly.”

During four high-profile arrests by RCMP on Wet’suwet’en territory, police were armed with semi-automatic weapons and used helicopters and dog units, Nivyabandi said.

Two weeks ago, the B.C. Supreme Court heard final arguments in the trial of Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chief Dsta’hyl, Adam Gagnon, who was arrested in October 2021. There has been no decision yet in the case.

On Nov. 29, B.C. Supreme Court Judge Michael Tammen found Dakelh land defender Sabina Dennis not guilty of criminal contempt for her role in a standoff that occurred on Nov. 18, 2021, determining she had attempted to play a peacekeeping role and was not intending to breach the injunction as RCMP officers carrying rifles and wearing military-style fatigues moved to arrest people.

Amnesty says the ongoing conflict has had wide-ranging impacts on the Wet’suwet’en.

“This devastating situation has negatively impacted individual land defenders as well as the Wet’suwet’en Nation as a whole,” Langlois said.

Pipeline construction has created an “atmosphere of fear,” she said, resulting in a loss of connection to the yintah, or traditional territory, and negatively impacting cultural transmission to future generations.

Chief Howilhkat, a member of the Unist’ot’en house group who also goes by Freda Huson, described how police and private security have followed and threatened Wet’suwet’en and their guests, ticketing them for things like muddy licence plates and cracked vehicle windshields.

“These intimidation tactics are used to try and prevent people from coming to our space for fear of being arrested,” said Howilhkat, who runs a cultural healing centre on the territory. “We can’t even access any of our traditional harvesting grounds for berry picking or hunting because security is always following us and preventing us from doing our cultural activities.”

The report also found that Coastal GasLink used “divisive tactics” in its consultation over the project, causing “profound divisions” within the Wet’suwet’en community that persist today, Nivyabandi said.

Both the pipeline company and government have pointed to impact benefit agreements signed with First Nations band councils along the pipeline route, including five out of six Wet’suwet’en bands, as evidence of support. But Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs maintain that they are the proper authority to consult on decisions made on the territory, something affirmed by the Delgamuukw-Gisday’wa court decision.

Gidimt’en Clan Chief Woos, who also goes by Frank Alec, said Coastal GasLink offered “huge piles of money to band councils” to win consent and undermine the house Chiefs, who consult directly with nation members through the Wet’suwet’en traditional governance system.

The report makes a series of recommendations to government, industry and the RCMP, Nivyabandi said, including immediately suspending all approvals for the Coastal GasLink pipeline, dropping criminal charges against land defenders and adopting measures to ensure injunctions don’t infringe on Indigenous rights.

Amnesty is also calling on the RCMP to “immediately halt the harassment, intimidation, unlawful surveillance and criminalization” of Wet’suwet’en land defenders and withdraw from the territory.

Finally, it called on Coastal GasLink and its parent company, TC Energy, to “immediately halt the use” of the pipeline and cease operations in Wet’suwet’en territory.

Last month, Coastal GasLink announced that its 670-kilometre gas pipeline had reached mechanical completion. It had previously faced delays as a result of protests and the COVID-19 pandemic, causing the project to go significantly over budget.

Its budget was expected to increase by a further $1.2 billion if construction continued into the new year. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: