On a crisp October evening, several dozen Southsiders gathered in the Grassy Plains School gymnasium to debrief after an exceptionally long and exhausting wildfire season.

“Congratulations on saving your Southside,” said Sharon Vare, chair with Chinook Emergency Response Society. “Everybody needs to give themselves a hand.”

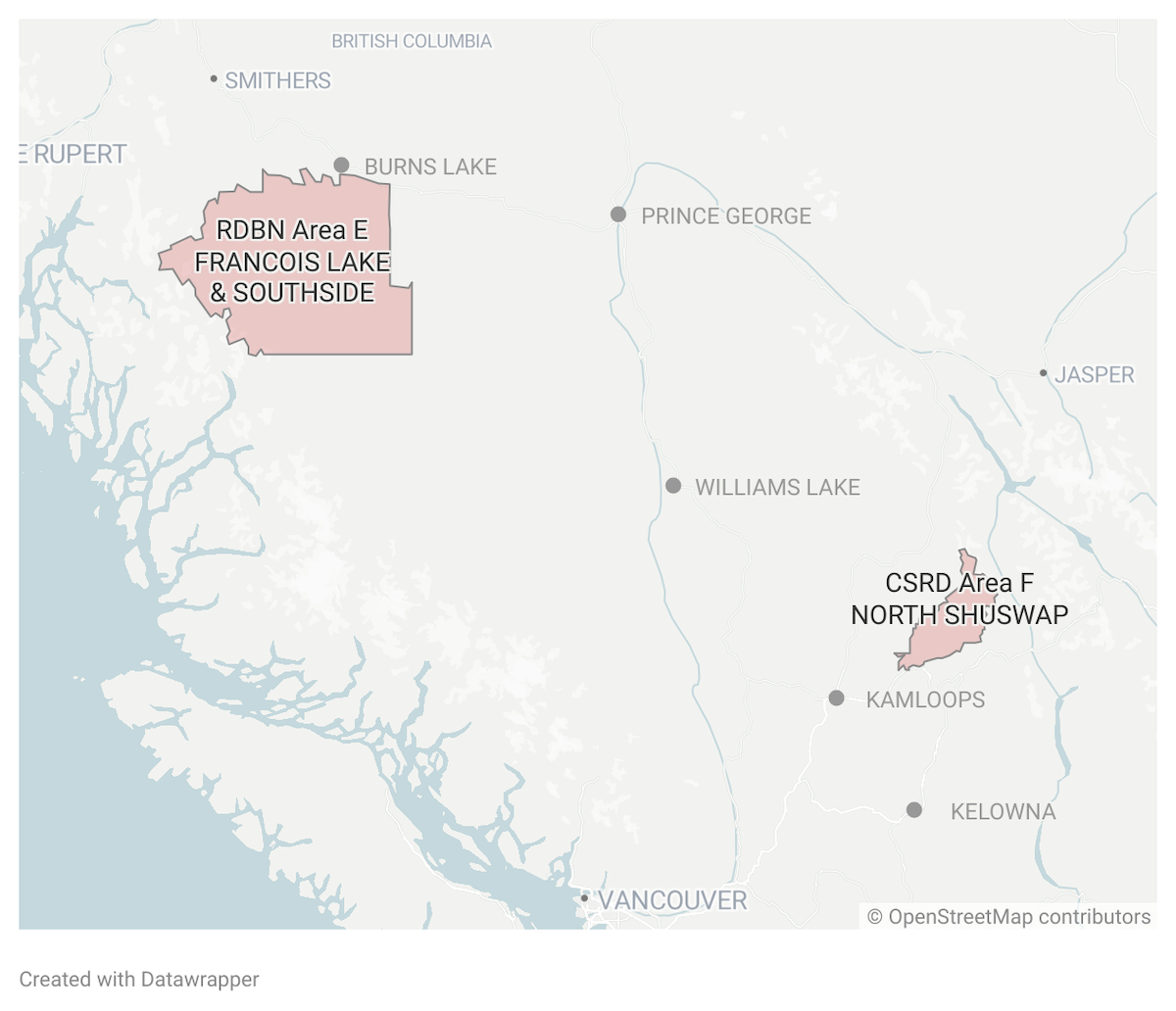

The rural area of Southside stretches from François Lake in the north to Ootsa Lake in the south. Located on the traditional territory of the Cheslatta Carrier Nation, its rolling landscape is dotted with small communities and is home to about 800 residents. Livestock outnumbers people 15 to one.

Fifty kilometres west of where the community meeting is taking place, the Little Andrews Bay fire continued to smoulder, tendrils of smoke lifting into the air and being batted about by the fall wind. The Little Andrews Bay fire was just one of more than two dozen wildfires that locals responded to this summer. Any number of them could have led to a summer like 2018.

No one in Southside will forget 2018. It was the year the community lost eight homes, 45 other structures and almost 200,000 hectares of forest.

“That’s not going to happen again,” Mike Robertson, another director with the society, told the crowd. “We are not going to have 2018 happen again.”

In addition to property and timber, residents also lost their freedom, Robertson reminded those gathered in the gymnasium. When they were ordered to leave, those who remained behind to fight the fires faced a heavy-handed police response and criticism from politicians who accused them of putting people at risk.

In the wake of that season, the community got together and formed Chinook Emergency Response Society, also known as CERS, which provides local communication, co-ordination and education for wildfire response, but does not directly fight fires. Its purpose is to build relationships, its volunteer directors say — both within the community and with government agencies.

The journey to establishing CERS hasn’t been an easy one and the work is ongoing. But five years after the organization was established, it is being held up as an example of how communities can work alongside the BC Wildfire Service and other government agencies to co-ordinate wildfire fighting, better avoiding losses and tragedy.

In other words, CERS could provide a road map for other communities that want a role in wildfire response — like in the Shuswap, where many residents defied evacuation orders this summer to stay back and fight, leading to clashes with authorities.

Amid record fires, RCMP checkpoints

Until this summer, 2018 stood as B.C.’s most destructive wildfire season on record.

But this season far surpassed it. Across the province, 2.8 million hectares burned — twice as much as in 2018.

The season started early, with the first fires flaring up in April. In July, lightning storms combined with extremely dry conditions sparked wildfires across the central Interior.

By August, Southside residents were watching as the same frustrations they experienced in 2018 played out 600 kilometres to the southeast in North Shuswap.

“It was a replay,” said Risé Johansen, a founding member of CERS and its past chair, about the government response. “We feel like we’ve made progress here, but they do exactly the same things, they make all the same statements.”

North Shuswap and Southside are similar in many ways. Both are rural areas scattered with small, unincorporated communities. Either by nature or by necessity, residents tend to be self-reliant. Many have jobs in forestry or agriculture, work that makes them intimately familiar with the land. They have the equipment, skills and experience to respond to wildfires.

But those who defied evacuation orders in both places found themselves threatened with arrest, denied access to essential supplies and treated like criminals at RCMP checkpoints. In 2018 and 2023, residents resorted to ferrying equipment, fuel and food across lakes in the dead of night, navigating not just the dark waters but the police boats patrolling them.

Authorities also blamed community members for getting in the way of wildfire response.

“The BC Wildfire Service cannot use aircraft to do a direct attack on wildfires if they know there are civilians in the area,” Bowinn Ma, B.C.’s minister of emergency management and climate readiness, said of Shuswap residents during an August 2023 media briefing. Former B.C. premier John Horgan spoke similarly about Southside five years earlier.

But community members in both Southside and the Shuswap say they stayed in part because they didn’t see wildfire crews showing up.

“There were more police here than forestry or wildfire,” said Angela Lagore, who lives on an acreage near Shuswap Lake. RCMP confirmed that it had 76 officers in the area as wildfires threatened Lagore’s home this August.

Everyone The Tyee spoke with agreed that some residents should not remain behind in an evacuation zone. But those who did said they understood the risks and always had egress in mind — they had their escape route planned and a threshold for when they would leave. It felt important to them to fight for their communities, they said, and provide mutual aid when disaster threatened.

“It’s people who've been here a long time, know each other,” Lagore said about North Shuswap neighbours who supported one another this summer. “It's a very, very close community.”

Even as the province was asking North Shuswap residents to leave this August, the BC Wildfire Service was giving credit to Southsiders and the role that community members can play in wildfire response.

“We had the community of Southside really step into the effort in 2018,” Cliff Chapman, BCWS director of provincial operations, said at the August media briefing. “We continue to open up this opportunity for communities to work with us.”

As B.C.’s wildfire season becomes longer and more intense, provincial firefighting resources are increasingly stretched thin. This year, B.C. imported about 1,665 out-of-province wildfire personnel to fight fires, some from as far away as New Zealand, Brazil and South Africa.

Engaging locals in rural communities who want a greater role fighting fires could provide a possible solution.

This is something BCWS said it’s already doing through established partnerships with First Nations, local fire departments and, to a lesser extent, community groups like CERS. It just needs to be done right, said Ryan Chapman, deputy manager at BCWS’s Northwest Fire Centre.

“There's no question that more people at the right place at the right time with the training, skills and in an organization that is easy for us to collaborate with, that's what we want,” Chapman told The Tyee.

Last year, the province moved toward further integrating communities into wildfire response with a two-year project that seeks to expand co-operative wildfire response.

A point of contact and basic training are all that’s needed, Chapman said. But ideally, that happens outside of wildfire season and not in the heat of the moment.

‘It was Day 12 before we saw BC Wildfire Service’

By the time community members and BCWS finally started working together in North Shuswap this summer, frustrations had already boiled over.

In mid-July, lightning had ignited fires on either side of Adams Lake, north of Shuswap Lake in southern B.C. In the weeks that followed, the Lower East Adams Lake and Bush Creek East fires pushed gradually south, eventually forcing evacuations near the southern tip of Adams Lake on Aug. 2.

When high winds and dry conditions combined to drive the fires even farther south toward communities on the north shore of Shuswap Lake in mid-August, things moved quickly, leaving no time for communication.

On Aug. 17, BCWS lit a backburn, a technique that uses fire to fight fire by reducing fuel in a wildfire’s path, in an effort to slow the spread of the Lower East Adams Lake fire.

As the winds picked up that night, the fire swept back into communities along the north shore of Shuswap Lake, destroying nearly 200 homes.

Days later, BCWS called the planned ignition “largely successful.” Reducing fuel loads had slowed the fire’s intensity and saved hundreds of homes in North Shuswap, the wildfire service said. No homes were lost as a direct result of the backburn, it said in an emailed statement this fall.

The two fires are now considered to have merged into the Bush Creek East fire, which was last updated by BCWS at more than 45,000 hectares.

Local resident Jim Cooperman, who hired an expert to assess the burn, disagrees with BCWS.

While his home was spared, he blames the planned ignition for destroying 90 per cent of his property and homes in North Shuswap. He has filed a complaint with B.C.’s Forest Practices Board, which is investigating.

As the fire bore down on Aug. 18, Lagore heard propane tanks exploding in nearby Scotch Creek, 10 minutes to the west. By the time an evacuation order was issued, Scotch Creek and communities to the east, where Lagore lives, were already cut off from the Trans-Canada Highway. Residents were evacuating by boat.

She got in her vehicle and drove the opposite direction, an hour north to Seymour Arm.

“My dad and my brother stayed behind,” Lagore said. They gathered their equipment in the centre of a green pasture and spent the night fighting the fire, saving her sister’s home.

Lagore returned home the next day, shocked by what she saw. Fires were burning everywhere. She parked her fifth wheel in the field, joined more than 50 other community members and got to work.

“We didn't stop because there were so many structures being taken,” she said.

Lagore’s family has lived in the Shuswap for generations, working jobs in forestry, farming and wildfire. Her dad has stories about the days when someone would spot a fire and head to the local bar. “That bar would clear,” she said, as people went to fight the fire.

Today, she said, wildfire response has become “too political.” Lagore was appalled to hear politicians blame locals for hampering wildfire response. For nearly two weeks, there was no sign of firefighters in the area, and North Shuswap community members worked alone to build fireguards, she said.

“It was Day 12 before we saw BC Wildfire Service,” she said.

Those who weren’t fighting the fires helped in other ways. Police told Lagore, who owns a restaurant in Scotch Creek, that she couldn’t access her business to cook for people. So she emptied the fridges and brought the food to the frontlines. Others raided their neighbours’ freezers to salvage the rapidly thawing food before it went to waste.

Five years earlier, Southside resident Risé Johansen found herself in a similar situation. Even though she had a wildfire crew stationed at the resort she owns on Takysie Lake, RCMP officers stationed at the ferry terminal tried to prevent her from resupplying. She was forced to undergo a bureaucratic permitting process in order to bring in the food and fuel needed by locals and firefighters.

“I thought, if I ran a business that way, I’d be out of business,” Johansen said. “The lack of communication, I didn’t understand it at all.”

Just because residents don’t see them doesn’t mean they’re not there

According to officials with Columbia Shuswap Regional District, just because wildfire crews weren’t seen in North Shuswap this summer doesn’t mean they weren’t fighting the fires.

“The thing about BC Wildfire is that they’re fighting fire up in the hinterlands. They’re on top of mountains. They're in the middle of the bush, putting in guards and digging trenches,” said Derek Sutherland, CSRD’s team leader of protective services. “Nobody ever sees them.”

While wildfire teams worked in the bush, local residents wanted the freedom to patrol their neighbourhoods and extinguish spot fires. That was illegal under the evacuation order, according to the RCMP, who set up roadblocks and threatened to arrest anyone who left their property. If you left, you couldn’t return, residents were told.

“We couldn't put out a fire on our neighbour’s lot or we couldn’t go from Lee Creek to Scotch Creek to help with a big blaze there,” said Jay Simpson, who is the elected representative for CSRD’s Area F. He was among those who defied the evacuation order.

Simpson said the assertion that firefighters needed locals out of the way to fight fires was “not really accurate.”

“We really didn't see much in the way of BC Wildfire in our communities at all,” he said. “Their efforts were out in the bush.”

The RCMP told The Tyee there were two arrests relating to evacuation orders in North Shuswap this summer. Neither resulted in charges. Two other incidents are still under investigation, it added.

One reason given for the access restrictions was reports of BCWS firefighting equipment being stolen. In an email, RCMP Cpl. James Grandy said that things like hoses and pumps were mainly “being moved from one location to another” by locals fighting fires.

But common sense didn’t always prevail, according to Sutherland. On three occasions, he said, sprinklers were taken from a wooden bridge and used to protect homes. That goes against emergency response priorities that rank health and safety first and protection of property lower down, he said.

“If we lost that bridge, not only do we lose the critical infrastructure for the area, we lose access to that area. It jeopardized the health and safety of the first responders because they needed that bridge for egress,” Sutherland said.

“The biggest priority is life safety. We’re very proud of the fact that we didn’t lose any lives during this event. We lost 176 homes or structures, but nobody died.”

A way forward: including locals in organized wildfire fighting

As the smoke cleared after the Lower East Adams Lake fire merged with the Bush Creek East fire and tore through North Shuswap, BCWS sat down to talk with locals.

Everything changed, Simpson said. “They were quite happy to start working with us.”

To accommodate locals who wanted to be involved in the wildfire response, the regional district got “creative on the fly,” Sutherland said, working with BCWS to offer basic wildfire training to community members. More than 50 people in North Shuswap signed up to take the S-100 course, a two-day basic wildfire training for forestry workers and contract firefighters. Many were hired by BCWS the following day.

“It was a creative solution to a greater problem, to help address an immediate need, but the future of that needs to look different,” Sutherland said. “We need to go into these events with residents that want to stay behind already trained and ready to work within the BC Wildfire system so that everybody is safe.”

Several people suggested the S-100 course should be offered in B.C. high schools. It’s something already happening, on an optional basis, in some northwest schools, said Ryan Chapman of the Northwest Fire Centre.

Invariably, community members said that once wildfire crews and locals were on the ground, working toward a common goal, the relationship was, overall, positive.

“Most of what I saw was fantastic,” said Jayson Warkentin, a Lee Creek resident who stayed behind in North Shuswap this summer to fight fires. All it takes is good oversight and direction, he added.

“[BC] Wildfire, the fire departments and the government need to show up and provide that direction,” Warkentin said. “The collaboration that was going on on the ground, when it occurred, it was great.”

These kinds of collaborations can also be helpful when wildfire fighters and police officers arrive in an area without understanding the local context.

Carol Imus, who has lived on François Lake with her husband, Steve, for 40 years, remembers the police officers who arrived at her home during their first evacuation order five years ago.

“They weren’t the politest,” she said. “We had no officers from our area. These were from Surrey, Vancouver, Abbotsford and Burnaby. They didn’t know where they were; they didn’t know where the fire was.”

The area has spotty cellphone coverage and police had set up a checkpoint down the road where there was no service. Imus was tasked with relaying messages for them. But if they’d moved their roadblock 100 metres to the east, they would have had reception, she said.

That fall, Imus attended the community meeting arranged by Southside residents Johansen and Clint Lambert that resulted in the creation of CERS.

Today, Imus is a CERS director and the pod leader for her area. In an emergency, the call goes to her and she alerts neighbours — an old-fashioned phone tree. CERS keeps records on available equipment and volunteers and is responsible for co-ordinating a local response.

When a second wildfire-related evacuation order came in this summer, things looked much different than in 2018.

“It was just a 180-degree difference this year,” Imus said. In addition to having local RCMP officers in the area, a local BCWS incident commander was also willing to work with CERS to co-ordinate their respective activities.

Chapman, with the Northwest Fire Centre, agreed that a more localized response is ideal. But he said juggling BCWS resources provincewide means sometimes relying on external help. “It’s a delicate balance,” he said.

How CERS has pitched in — and how the province is adapting

Southside resident Clint Lambert, a founding member of CERS, spent months fighting fires in the area in 2018 and this year, much of that time unpaid before BCWS met with the team and hired them on contract. He estimates his unpaid out-of-pocket expenses for time, fuel and equipment at $120,000.

His experience prompted him to run for local government.

“The first thing I’ll tell you is, never do anything in anger,” he joked this fall, five years after being elected director for the Regional District of Bulkley-Nechako’s Area E, the 16,000-square-kilometre area covered by CERS.

He has pushed the regional district for a more localized wildfires response. This summer, CERS managed a checkpoint near Ootsa Lake. This meant locals were in charge of determining who had a legitimate reason for being in the evacuation zone.

Lambert also worked with the local François Lake ferry operator to give BCWS priority access, the same status granted to emergency responders like police and ambulance, so that wildfire crews could respond in the middle of the night.

Other initiatives included nine trailers filled with basic firefighting equipment, funded by Cheslatta and Rio Tinto Alcan, which have been placed throughout Southside and north of François Lake. Anyone who spots a fire can hook up a trailer and respond immediately. Plans are underway to add three more before next summer.

In recent years, CERS has also added signage throughout Southside to indicate where cell coverage exists — a simple concept that could prove invaluable in an emergency.

In September, B.C. Premier David Eby announced the province would convene an expert task force on wildfires and other emergencies caused by climate change. He cited the “devastating impact” of this year’s fire season and acknowledged the dedication of first responders, BCWS and the Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness.

The premier also recognized the role of community volunteers.

“It was also clear to me that we could be doing a better job of leveraging local knowledge and expertise when it comes to preventing and fighting wildfires,” Eby said.

In North Shuswap, residents had mixed reactions to the news.

“I have no faith in anything the government does,” Cooperman said. The local guidebook author said he doesn’t plan on participating in the task force and is instead focused on writing a book about the fire.

But others said they welcomed the opportunity to provide feedback. “I feel an obligation to get involved,” Warkentin said, “because I think the help is needed.”

As the Southside community gathered last month, Robertson announced that Cheslatta Chief Corrina Leween had been invited to join the task force. She agreed on the condition that she could attend with a team that included the nation, CERS and the regional district.

“That way, she speaks with a voice that includes everybody,” Robertson said. “It’s going to be all of us.”

The first thing they’ll be presenting is CERS as a model for other communities, he added. Already, people across Canada have reached out with an interest in implementing something similar in their communities, the directors said.

A work in progress

By October, CERS volunteers were busy inventorying and servicing equipment, writing grants and planning training sessions. Already, they were looking ahead to the next wildfire season.

Over the winter, they plan to meet with local authorities — like BCWS, RCMP, the BC Ambulance Service and the regional district — to keep lines of communication open and build relationships.

It’s a work in progress, the directors said.

Chapman, with the Northwest Fire Centre, agreed. “It’s going in the right direction,” he added.

It’s impossible to know how many catastrophic wildfires volunteers may have prevented in Southside this year. Of the 27 fires they responded to, a dozen were put out within hours — less time than it would have taken for provincial wildfire crews to arrive.

“Any one could have been a major event,” CERS co-ordinator Scott Zayac said.

CERS directors estimate their efforts saved the province millions of dollars in firefighting costs. What they saved the community is immeasurable.

“A lot of us spent a lot of money on community firefighting this summer. So be it. We have our houses. We have our community,” Lambert told the group gathered at Grassy Plains School. “I just can’t say enough good about this community.”

Uncertainty remains about what evacuation order restrictions could mean for locals if another big fire threatens communities. But Southsiders hope that by keeping lines of communication open and working with local authorities, residents can avoid the heavy-handed and bureaucratic response they faced in the past.

They want to work proactively with government. But it’s a fine balance, they said. Because they also want the independence to approach wildfire response in the way that works best for them.

“It’s neighbours helping neighbours,” Vare said. “Relationships — that’s all we really are.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: