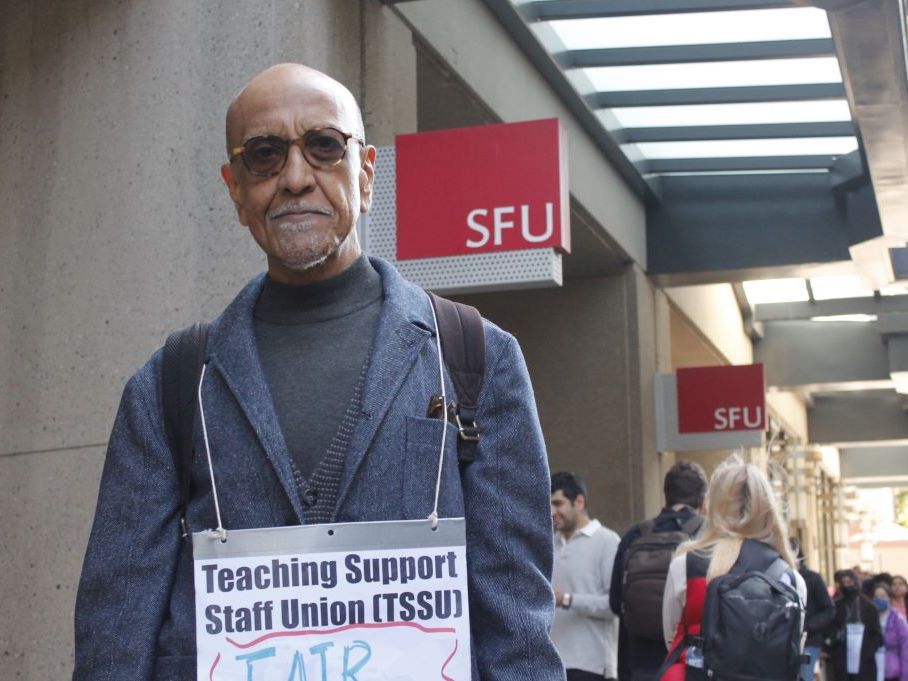

Professor Amyn Sajoo was supposed to be teaching a class at Simon Fraser University about political resistance.

Instead, he was on a picket line.

Sajoo is one of 1,600 SFU teaching staff who have been on strike for more than a week after negotiations between the school and the Teaching Support Staff Union, or TSSU, broke down.

Teaching assistants and professors marched in a circle outside the school’s downtown Vancouver campus, yelling slogans and banging drumsticks against orange plastic Home Depot buckets.

Some on the picket line are graduate students struggling to make rent. Others are English teachers who have never had pensions. And some, like Sajoo, are nationally recognized scholars who have taught at SFU for years but have never had a permanent job.

What unites them, they say, is membership in the ivory tower’s underclass — a growing group of precarious workers that Canadian universities rely on to educate the next generation.

Observers say the strike at SFU embodies a growing labour crisis in higher education as universities deepen their reliance on contract workers and graduate students to teach a growing number of students.

This isn’t unique to SFU. But the TSSU is hoping it can set a new standard for such workers by forcing the university to improve pay, guarantee pensions and improve job security for contract faculty.

So far, they haven’t had luck. SFU has said it cannot meet the union’s demands because of rules set by the provincial government, which makes the final call on how much public employers can offer their unionized workers.

That hasn’t deterred the TSSU, which says the rising cost of living has pushed its membership to a breaking point.

“We’re teachers in a teaching institution. How did we become an underclass in the university?” said Carol Condruk, a longtime educator with the school’s English language and culture program. “How is it possible?”

Bouncing between contracts

Sajoo is no new professor. He’s penned three books, has testified before Canada’s Senate and has spent years teaching SFU students about global human rights.

But he’s never had a steady job.

Sajoo is one of hundreds of contracted faculty at SFU bouncing between annual contracts, never knowing for certain if he’ll be renewed or if he’ll find a path to a permanent job.

Recently, Sajoo thought he finally had his chance. He had finished four straight years as a fixed-term lecturer. Under his collective agreement with the SFU Faculty Association, that meant he would get a shot at a continuing position.

But instead, Sajoo said, he was offered a different contract as a sessional instructor. That meant he moved to a new union — the TSSU — and was no closer to permanency. He also took a pay cut.

“Because I was under the one-year contract arrangement, they were paying about $90,000. Now, because I’ve run out of the four-year cycle and they refuse to offer me a continuing position, now my salary for teaching exactly the same courses has gone down to $60,000,” Sajoo said.

SFU Faculty Association executive director Brian Green says that kind of precarious work is common — at SFU, and at universities across the country.

A 2018 study from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Canadian Union of Public Employees suggests that, in that year, as many as half of faculty across Canada were contracted.

Contract professors often do a big chunk of teaching work. But they rarely get a chance to do research, have relatively few benefits and are paid far less than their tenured peers. And, most vitally, they don’t have any guarantee of a steady job.

“We have a significant amount of university teachers who are just jumping from course contract to course contract,” Green said. “They have no job security, no pensions, and are paid a fraction of what other professors are paid. It’s unconscionable, and it’s unsustainable.”

SFU says it had only about 190 sessional instructors on payroll in the fall term and that they taught fewer than 11 per cent of courses. But Derek Sahota, an advocate with the TSSU, says the union counts 300 sessionals who are actively employed at the school. And Green says the school’s numbers exclude other categories of contract workers who often teach some of the largest courses at SFU.

“They are critical. It varies from department to department. But there are huge numbers of courses that are taught by sessionals and fixed-term faculty,” Green said.

Both the faculty association and TSSU have tried to improve conditions for contracted teachers through clauses that give them a bridge to a full-time job.

But Sahota says SFU has avoided those clauses by bouncing them between different types of contracts.

“We’ve seen people bounce back and forth over a period of decades just to avoid hiring them into continuing jobs,” Sahota said.

Peter McInnis, president of the Canadian Association of University Teachers, says SFU is not an outlier. There’s been a persistent trend, he says, of Canadian universities replacing tenure-track professors with academic “gig workers.”

McInnis believes it’s a cost-cutting measure that was driven initially by necessity as provinces slowed investment in higher education.

But now he worries those contract faculty are becoming a “permanent underclass” with no way of moving up.

“Most people working as contract academic staff want a tenure-track job. They want some permanency. They want something that is more reliable,” McInnis said.

Sarika Bose, an English lecturer at the University of British Columbia, says schools like hers have taken some positive steps to improve salaries and benefits for short-term staff.

But she says the uncertainty — and rising costs — means the job is still unsustainable.

“It affects your spouse. It affects your children. Can you have a permanent place for them to live? Can you enrol your children in certain kinds of programs and services from one year to the next?” Bose said.

21 years, no pension

The SFU and the TSSU met 41 times over the course of more than 18 months before the strike kicked into full gear.

TSSU members — who include sessional teachers, teaching assistants and educators in the school’s English language and culture program — have been off the job since late September.

The strike has hamstrung one of the province’s largest universities. Swaths of classes have been cancelled by rotating picket lines across its three Lower Mainland campuses. When picketers threatened to disrupt a convocation ceremony, the school hastily struck a deal with the union to let it proceed. Last week, the TSSU got a boost from an unlikely place: Toronto Raptors player Garrett Temple, who swung by a picket line before the team’s game in Vancouver that night.

But the two sides still haven’t reached a deal.

The TSSU wants higher wages, more job stability for sessional workers and pensions for employees who currently are not covered under any plan.

But SFU says meeting those demands will be impossible.

In B.C., public sector employers have to bargain under a central mandate. That means every public sector union gets a variation on the same deal.

Those proposed deals all have to be approved by the Public Sector Employers’ Council Secretariat, or PSEC, which is controlled by the provincial government.

The purpose of the cap is to control government spending, and so that smaller employers — like regional colleges — can compete with wealthier competitors like major universities or Crown corporations.

So far, B.C.’s Ministry of Finance says 97 per cent of employees in the public sector have tentatively or formally accepted a version of that deal. The TSSU and the SFU Faculty Association are among the last holdouts.

That hasn’t deterred the TSSU, which insists that the school could find a way to meet its demands if it got creative.

“What SFU does is use the PSEC mandate as a shield to not make any changes,” Sahota said.

Some of those requests are not directly related to salary.

Condruk, who works in the school’s English language and culture program, delights in teaching international students how to work and think in a new language.

She has been an SFU employee for 21 years but never received a pension.

Years ago, TSSU members were invited to join B.C.’s College Pension Plan. But the move would have included liabilities of about $40 million a year, which SFU asked the TSSU to pay out of its own end. It declined.

Condruk says a pension doesn’t matter for her now: she’s nearing retirement. But she says the job is increasingly unsustainable for new people entering the profession.

“We have stayed in our program because we love what we do, we love each other and we love our students. And we just want to keep doing it,” she said.

For other TSSU members, the strike’s outcome is even more urgent.

Graduate student Tintin Yang says she works two part-time jobs at SFU, as a teaching assistant and a research assistant. She’s also won scholarships. But she says she’s now considering taking on a third job to pay bills, which could extend the amount of time it takes to complete her degree.

“This is how people get stuck at being at university for four, five years for a master’s degree, and the university keeps exploiting them for their labour,” Yang said.

Teaching assistants like Yang are in a different situation than sessional instructors. They skew far younger and generally work their jobs only while concurrently studying at the school.

But, like sessional instructors, they say they do a lot of front-line teaching by leading tutorials and seminars. And they often do a bulk of the grading, Yang said, which frees up faculty for other work.

For many, those gigs aren’t a way of making extra pocket money: they depend on them to pay for rent, food and other necessities that have become dramatically more expensive in recent years.

SFU acknowledges times are tough. In an emailed response, communications staffer Will Henderson said the university is “working on additional forms of graduate student support, including establishing a university-wide minimum funding level for PhD students by the end of the fall term.”

But many students say that can’t come soon enough. Maria Sommers, a graduate communications student, says she had to take out student loans because her teaching assistant job paid $1,200 a month — less than her $1,300 rent. She says her current workload leaves her little time to complete her thesis, which means she has had to extend her studies.

She says other TSSU members are in even worse straits — increasingly struggling to pay the costs of food or rent as their wages stay stagnant.

“Maybe this is dramatic, but I do feel like it’s life or death sometimes. I feel so stressed all the time,” Sommers said. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Education, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: