In the middle of Burnaby’s bustling Metrotown is a bridge to nowhere.

The concrete pedestrian walkway begins on the second floor of the Metropolis supermall, stretches over congested traffic of Central Boulevard and — just short of touching the glassy SkyTrain stationhouse — ends abruptly with a sheer drop.

The awkward appendage has been hanging around for seven years, here at the heart of what booming Burnaby is now calling its downtown. There are 6.6 million boardings at the Metrotown SkyTrain each year, making this the busiest station outside of Vancouver. And that doesn’t even take into account the boardings at the 14-bay bus loop where commuters zip off to other parts of the region.

In plannerspeak, the overhead pedestrian bridge is called a “passerelle.”

For years, the passerelle allowed commuters stepping off the Metrotown SkyTrain to avoid the street traffic below, connecting them to a pedestrian walkway that led to a number of destinations: the Metropolis mall, the Station Square mall, the bus loop and three Metrotowers, which have a combined total of 87 floors of offices.

But when Metrotown got a new stationhouse in 2017 to replace an aging one, it didn’t come with a new passerelle. And now the large number of people who depended on the old passerelle to go shopping, get to work or hop on transit are all forced onto the street, where they have to cross Central Boulevard to get where they want to go.

News media reported on the inconvenience at the time, not to mention the danger of crowding an already crowded intersection. Many commuters vented their frustrations on Reddit, calling it a “design fail” and “absolutely moronic,” wondering who thought that removing a pedestrian bridge and exposing people to car and bus traffic in the middle of a growing downtown was a good idea. Others lamented that it is now “very inconvenient” to grab burgers and burritos from the A&W and Chipotle on the other side of the bridge.

One Redditor wrote wistfully, “I can’t picture Metrotown without it.”

Dawn of Metrotown

So what’s the big deal about this bridge?

Well, just as the Romans had roads to link up the state, Metrotown had its above-grade walkway and the accompanying passerelle. (Bear with me here.)

In the beginning, there were three big landowners in Metrotown: the Ford Motor Co., which made vehicles for the Allies during the Second World War; the wholesale grocer Kelly-Douglas; and Simpson-Sears, with its retail and distribution centre. Together, their land made up one big superblock.

In December 1985, the SkyTrain arrived in Metrotown right at the dawn of malls and it was good.

In 1986, the Simpson-Sears property was redeveloped into Metrotown Centre, which kept the Sears store and added Woodward’s as a major tenant. In 1988, the Ford property was demolished for the Station Square mall. In 1989, the Kelly-Douglas property was redeveloped into Eaton Centre.

The walkway and passerelle were built to thread together the three neighbouring malls and connect them with the SkyTrain station and bus loop. The walkway also fed into the first of the Metrotowers, built in 1989.

Here on what was once an industrial superblock — with mixed uses, rapid transit and regional connections — were the makings of a new downtown.

A ‘dinky’ solution

I’ve always thought of the Metrotown neighbourhood as made up of hubs without spokes, organs without tissue. That’s because there are a lot of great destinations — the Crystal Mall, the Old Orchard Mall, the Metrotown library, the Bonsor Recreation Complex and the many businesses on Kingsway — but to get there you have to traverse narrow sidewalks, multi-lane crosswalks, seas of above-ground parking and the mouths of tunnels leading out of underground parking from which speeding cars emerge.

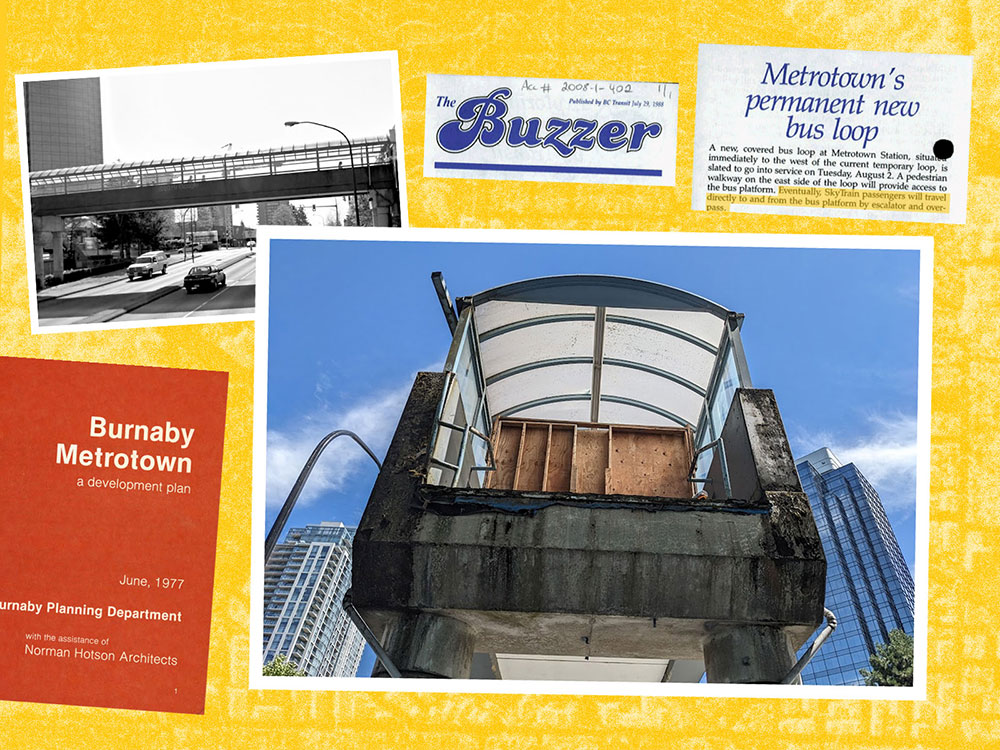

As early as 1977, Burnaby planners seemed to notice this problem. In a neighbourhood plan they suggested “a separation of important pedestrian ways from direct vehicular influence.”

The Metrotown walkway and passerelle were an answer to that problem, preventing people from urban island hopping, carrying them from the SkyTrain station directly to where they needed to go without ever having to fight traffic. Portions of the walkway were also covered, perfect for a region dubbed “Raincouver.”

Architect and planner Graham McGarva, an expert on transit-oriented development, calls the old passerelle “dinky,” but a “convenient solution.” McGarva has worked on many major projects in the Lower Mainland and beyond, such as the SkyTrain and Canada Line stations, during his time at VIA Architecture, of which he was a founding principal.

“It used to be the absolute two solitudes: transit, then development,” said McGarva. “It was an oil and water situation, one begrudgingly avoiding the other.”

A bridge too far

While McGarva didn’t work on the Metrotown station redesign that shuttered and didn’t replace the passerelle, he explains that such projects are complicated because they require co-ordination between multiple parties: the private developer, the municipality and the transit authority.

In 2007, a City of Burnaby report noted that the passerelle was used by 40,000 people per day and was too narrow to handle the growing traffic. By this point, Metrotown Centre and Eaton Centre had combined into the Metropolis supermall, B.C.’s largest shopping centre.

The passerelle was also not accessible. Because the walkway from the mall side was built after the station was, the height of the second floor did not match up to the mezzanine of the station. The eventual solution to this slight difference in height was to install three steps pedestrians needed to descend to get from the taller mall to the lower station.

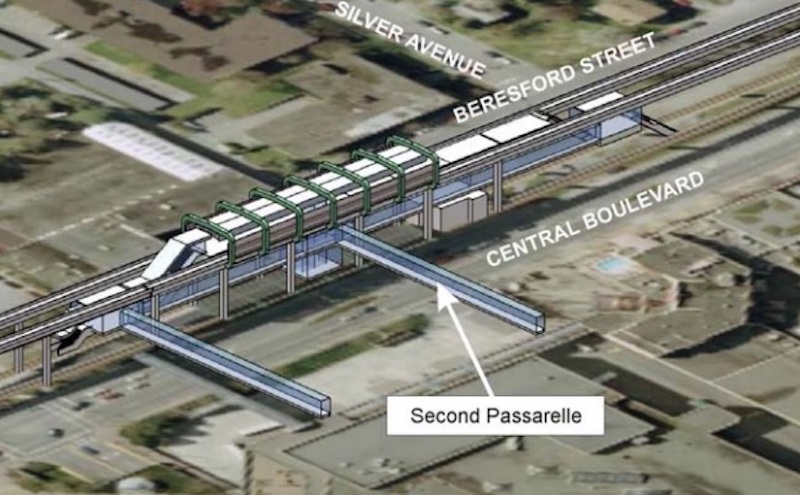

That city report called for a newer, larger passerelle to correct these problems. It even raised the possibility of a second passerelle to connect the station directly to Station Square, which the landlord was planning to redevelop.

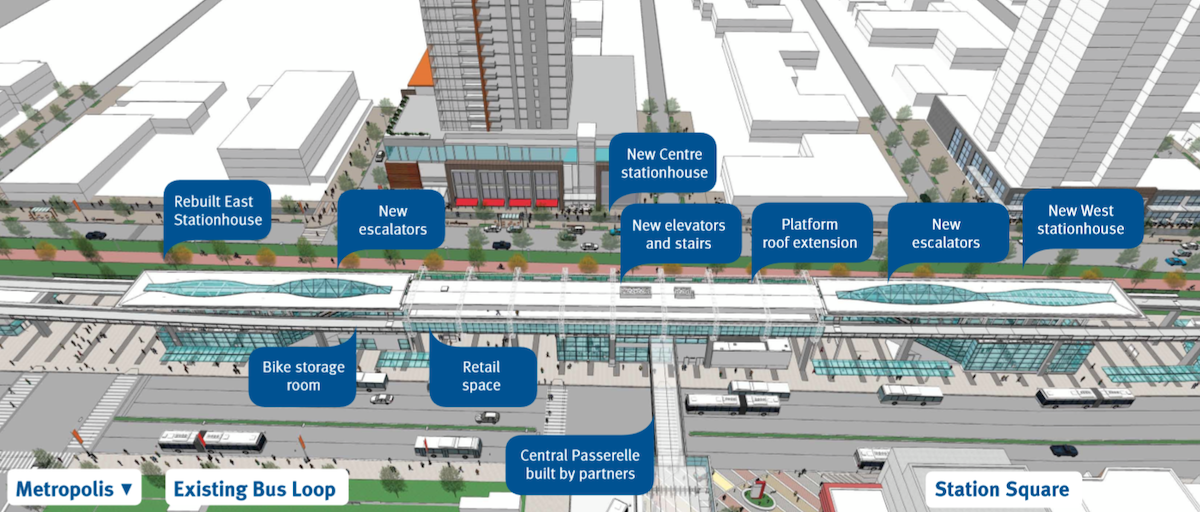

In 2015, construction began on a new stationhouse for Metrotown, with a replacement passerelle included. TransLink, aware of the significance of its role, put up large banners to alert commuters in three lingua francas: English, Chinese and Punjabi.

But the urbanizing neighbourhood seemed to be changing too fast for its own infrastructure.

The Metropolis mall is scheduled for demolition. It’s owned by Canadian real estate company Ivanhoé Cambridge, which is working with the city on a 100-year plan for future redevelopment.

One of the company’s vice-presidents called the mall too much of a “fortress,” and said that in order to truly turn the neighbourhood into Burnaby’s downtown, they would need to break it down.

The new plans will include both indoor and outdoor retail, with housing, parks, plazas, homes, and even a potential events centre. The space would then be connected with a street grid.

There’s also Burnaby’s plans to beautify and animate the BC Parkway, the pedestrian and cyclist route that runs along the SkyTrain and is rugged in parts, into a linear park of a corridor.

With these changes on the horizon, the replacement passerelle for a mall that would eventually be torn down was scrapped because it “didn’t make sense,” Burnaby’s public affairs manager Chris Bryan told The Tyee. When the time does come for a replacement, he added that the stationhouse was built with the ability to include it.

Passing the passerelle

The passerelle might not have the elegant gardens of the New York High Line. It may not have love locks, like Paris’ Pont des Arts and, at one time, Vancouver’s Burrard Bridge. It’s not the kind of place where lovers kiss; they’d be trampled.

But just ask commuters and they’ll lament its loss, especially since there isn’t construction planned for the mall just yet. If you’re looking for some choice words about its disappearance, I invite you to read this heated Reddit thread that blasts planners and the dangers of the new “hellscape.”

TransLink has admitted the “inconvenience" of its absence, a sentiment Coun. Sav Dhaliwal recently echoed to The Tyee.

Aside from the crowding, the fact that the SkyTrain station forces everyone down to the street has created something new. Just the other day, a busker was playing the electric violin while another on the guitar strummed the Jurassic Park theme song. Pan flautists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Krispy Kreme fundraisers and a grab bag of political activists are common sights too.

“It starts to bring the city down to grade,” said McGarva, the architect and planner. “It’s real urbanity. When the guys are doing ‘The end is nigh!' or selling hot dogs or busking, those are all signs that there are people passing through here, that this is a dynamic, vibrant place with an opportunity to skirt around.”

The husk of the old passerelle is still around, looking as if though it has been cut with a giant sword, exposing three steps that lead to nowhere. There was a city plan, and even money, earmarked for its demolition. But that fell through too.

And so this monument with its vast and trunkless legs of stone, this remnant of an older Metrotown and its Expo-era boom, stands another day.

It makes for a good punchline, though. Why did the pedestrian have to cross the road? ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: