If walls could talk, Fraser Wilson’s mural might never stop.

It has watched unions deliberate and plan. It has heard a live performance from the Grateful Dead. It has, at times, witnessed raves.

Most people who walk by the Maritime Labour Centre, located near Victoria and Triumph in East Vancouver, have never seen the 25-metre-wide visual ode to Vancouver’s working-class history.

Outside, this union hall looks like a boxy, beige building of uncertain origin and purpose. Passersby on a weekday morning might see a half-empty parking lot, a group of men chatting by a doorway, and a maroon sign marking the entrance to the centre’s auditorium.

But to Vancouver’s labour movement, this hall represents a disappearing part of their history, and a trove of treasures that celebrate it.

Wilson’s mural is one of three pieces of artwork the hall hosts, each salvaged from union halls that were sold or shut down.

For unions, these halls are places to gather, plan, celebrate and mourn. They host conferences, workshops, strategy sessions and sometimes funerals. And the Maritime Labour Centre is one of just two in Vancouver that still operates as an event space.

Today, the artworks it hosts are a reminder of the movement’s history — a living reminder of what was sacrificed and lost, and what’s been saved.

A union-organizing former Vancouver Sun cartoonist

Fraser Wilson was between jobs when he painted his ode to Vancouver’s working people.

Wilson had gotten into the art business as a young man. In the 1920s he took a job designing signs for an orange drink factory. He ended up taking a job at their Australian division, but the job was not to his liking. He complained the constant peeling of oranges caused his hands to swell.

He quit and found himself destitute. In 1985, he told a Vancouver magazine writer he’d spent six months living in Sydney’s Hyde Park. He claimed to have once survived 10 days on a few shillings’ worth of ginger snaps.

By 1947, Wilson was working as a cartoonist for the Vancouver Sun. But his union-organizing ways drew the ire of the paper’s management, and he got the axe.

That was the year Wilson was commissioned to do the mural at 339 W. Pender St., then the newly opened Boilermakers' union hall.

Wilson wanted his mural to be an ode to the industries and people that had built Vancouver — shipbuilding, logging, mining and maritime trade.

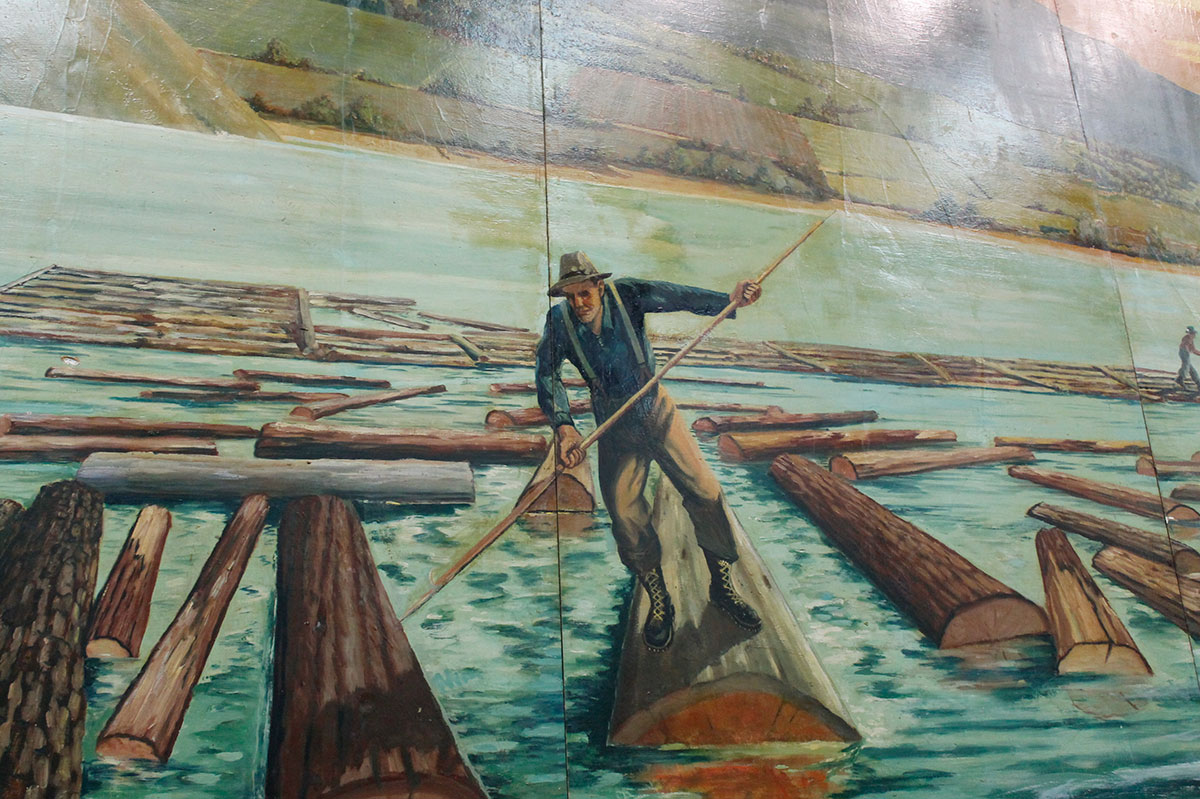

Mining carts ferry ore from the bowels of a mountain. Workers balance on felled logs. Shipwrights work in drydocks and a ship prowls the waters while the sun sets in the background. The artwork is a rare example of social realism, a style most associate with the works of artists like Diego Rivera or the famed murals of San Francisco.

Sean Griffin, a former writer for the labour paper the Pacific Tribune, whose father was a friend of Wilson’s, said the work was not meant to be nostalgic. But it did mean to honour working-class history in a way that often didn’t happen in public spaces.

“A lot of these guys weren’t about reminiscing. They were living in the present, working in the present and focusing on the politics of the day,” Griffin said.

Over time, the Boilermakers' hall became the Pender Auditorium. In 1966 it hosted the Grateful Dead. Boxing matches were common, too.

The mural became a symbol of what the labour movement had accomplished. One union member later wrote that the mural was their history and their heritage, a sign of how unions had helped improve the standard of living for countless working people in B.C.

But times changed. Strapped for cash, the Boilermakers who owned the Pender Auditorium sold the building. The Fraser Wilson mural was left behind. New owners planned to carve up the space into offices and paint over the art.

“They were just going to tear it down,” Griffin said.

To many labour leaders of the day, that was unacceptable. Dan Cole, then the president of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, wrote to officials at the time that tearing the mural down would mean “this valuable piece of Vancouver labour history will be lost forever.”

That sparked a rush to save it. Maritime unions, including locals of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union and the United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union, launched a last-minute bid to transplant the mural to their new space at the Maritime Labour Centre.

It was no easy task. Wilson had painted the mural in oils without using adhesive, and the piece was in bad shape. Transplanting it would require months of work, a careful hand and tens of thousands of dollars.

But the unions had the gift of timing: Vancouver’s centennial was approaching, and local politicians of the day were keen to spend cash on preserving and showcasing the city’s heritage.

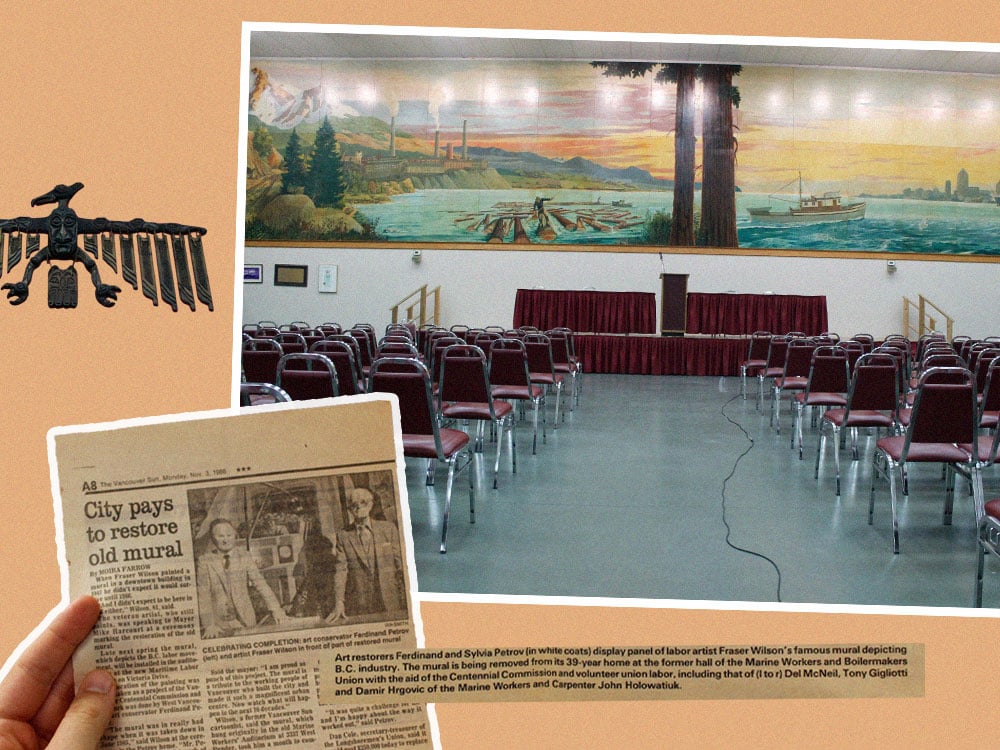

The city’s centennial commission committed $23,000 to the project, along with another $14,000 contributed by various unions in the way of money and labour.

Ferdinand Petrov, a Hungarian art restoration expert, meticulously removed the mural from the wall and glued it onto heavy canvas, which was then mounted onto 43 separate plywood panels.

It wasn’t perfect: the wall of the Maritime Labour Centre auditorium was five metres shorter than that of the Pender Auditorium, meaning several panels were discarded. Wilson had to repaint parts of his mural, and one of the other panels mysteriously went missing.

But the restored mural was eventually unveiled to great fanfare at the Maritime Labour Centre. Then-mayor Mike Harcourt said he was “proud as punch” of the project.

A jailhouse gift

The mural isn’t the only rescued piece of art in the centre. On the other side of the auditorium hangs a wooden carving of a bird in flight, with a face growing from its chest.

The legend goes that this carving was given to fisherman’s union leader Homer Stevens during an 11-month stint in prison in the 1960s. Stevens had been imprisoned for contempt of court after he defied a court order that would have compelled his members to work during a strike.

“It was traumatic in a sense, but he warned us it was coming,” said John Stevens, Homer’s son. John was 13 when his dad was sent to jail in Chilliwack. When Homer came back, John said, it wasn’t long before the carving appeared. John said his dad told him the artwork was a gift to thank him for his advocacy for Indigenous peoples, both as a union leader and when he was behind bars.

“He made a point of making friends and seeing what he could do to help,” Stevens said.

To this day, no one knows exactly who carved the bird, where they were from or what exactly the artwork depicts.

For decades it hung in the former fisherman’s union hall on Cordova Street.

Jim Sinclair, a longtime organizer with that union and a former president of the BC Federation of Labour, said such halls were not just for work. They hosted funerals, celebrations — any event to help its members. As time went on and the private sector union membership declined, many unions were forced to either consolidate or sell their halls entirely.

Eventually, in the 1980s, the fisherman’s union decided to join forces with other unions to open the Maritime Labour Centre.

The Cordova Street hall was sold to the Salvation Army. After the sale was announced, Sinclair remembers one fisherman getting a last crack in at the old hall: “He said, ‘At least the preaching won’t stop,’” Sinclair remembered.

When the Maritime Labour Centre opened, the carving came with it. So did a mosaic art piece showing fishing vessels doing their work on the water.

Raves and ‘close calls’

Even after consolidation, however, the unions that ran the Maritime Labour Centre struggled to keep its doors open. Two of them ended up selling their equity in the building.

One way the Maritime Labour Centre made money was by renting out the building’s auditorium to anyone who wanted it. In the 1990s and 2000s, that often meant dance music enthusiasts.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s the hall hosted dozens of raves, until building manager Alex Pyck said there was one close call too many with Fraser Wilson’s priceless mural.

“It’s just too risky with that piece of history on the wall,” Pyck said.

“Every time we had a rave there would be a close call. Nothing would come into contact with the mural, as far as I know, but there would be damages to the wall around the mural. So we said that’s that.”

For now, at least, the Maritime Labour Centre has stayed open, sometimes against the odds. Today, it hosts the Vancouver & District Labour Council. Other union locals rent its offices, too. On any given day, you might find a conference, a union workshop, a banquet, and a little piece of Vancouver’s history that would have otherwise been lost.

The existence of the centre gives the people in the community a sense that labour is bigger than one union, Sinclair said. “It’s a movement.” ![]()

Read more: Art, Labour + Industry, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: