“It looks like a plank,” Scott Galligos says, peering into a cavity just above the high tide mark on the shoreline of a sheltered bay in Desolation Sound. He gestures to Colleen Parsley, the group’s lead archaeologist, to come have a closer look.

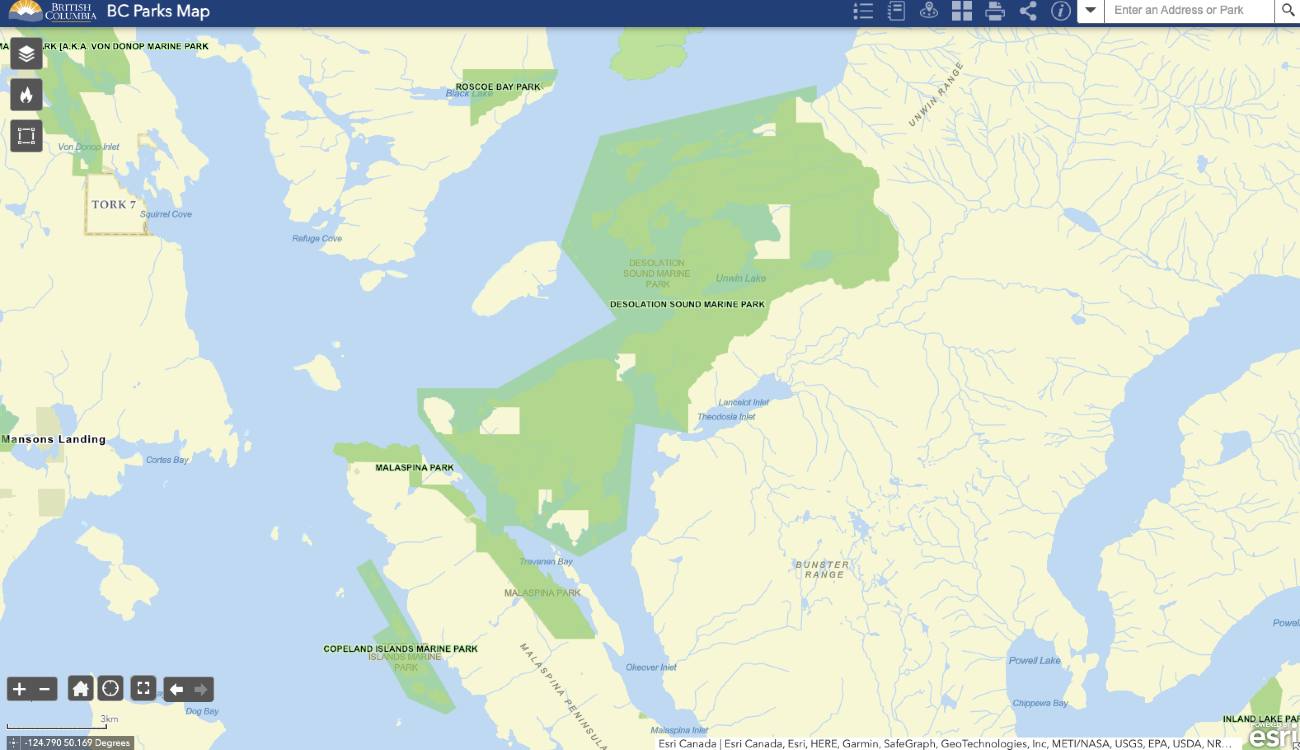

I am tagging along with the four-person group — Scott Galligos, a Tla’amin Nation culture and heritage field technician, Parsley, Alexis Rubletz, a Tla’amin Nation casual culture and heritage field technician, and Gerry Galligos, a Tla’amin Nation lands officer, who is captaining the boat — on the last day of the first phase of a project that will inventory, and ultimately protect, vulnerable archeological sites in Desolation Sound. The 8,449-hectare provincial marine park is north of B.C.’s Sunshine Coast and welcomes 250,000 annual visitors.

If what Galligos has spotted is in fact a cedar plank, it could be a burial box fragment. Coast Salish people recognized the preservative properties of cedar over 1,000 years ago, Parsley told me earlier. The dead were wrapped in cedar blankets and placed in cedar burial boxes; their bodies could be preserved this way for hundreds of years.

Parsley crouches down, then kneels. She aims a light towards the piece of wood Galligos identified.

“It’s a piece of two by four, Scotty!” she calls.

The solemn tension that had built up dissipates, and the group jokes about what the tide brings in. We make our way down the rocky beach, which is covered in invasive Pacific oysters and slippery bladderwrack.

Gerry Galligos pilots the group’s aluminum landing craft up to the rocks, and we hop back on, ready to travel to our next destination.

Over the past two weeks, the group has visited over 50 locations in Desolation Sound. They recorded new and updated information about 35 archeological sites, including four new burial sites, some of which could date back 1,200 years.

Desolation Sound Marine Park, which is in the territory of the Tla’amin and Klahoose nations, was established by the province in 1973 without the permission of those nations.

Archeological work done in the 1960s and '70s initially identified over 77 archeological sites. In the intervening years, 10 more sites have been identified. In addition to seeking out new sites, the current team will revisit some previously identified sites to assess them and add detail. The oldest known site in the immediate area, just outside the park, dates back 7,800 years.

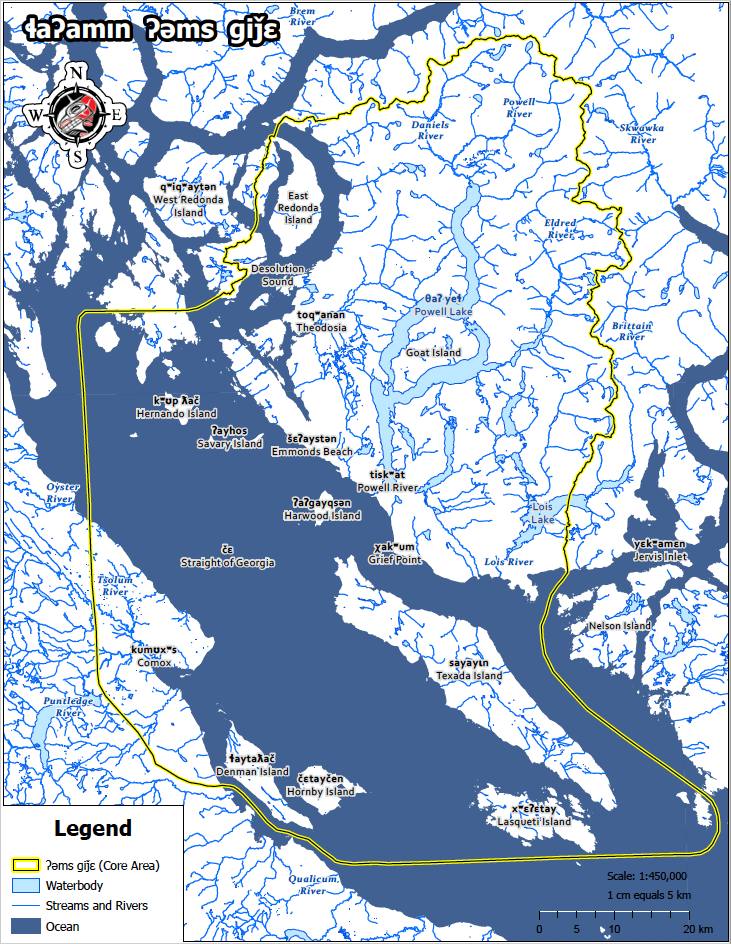

“Just like any other place within our territory, it was our home,” says Tla’amin council member Tiy’ap thote Erik Blaney. “It was full of resources that we use to survive. You know, we want to say the main village site was at tiskʷat, but we had main village sites all over the territory.”

Prideaux Haven, one of the most popular destinations for tourists visiting Desolation Sound, was also likely one of the most populated and significant spots Tla’amin people lived.

“You can really tell by the clam gardens that are in the area,” he says.

It is this overlap between the site’s popularity with tourists and its abundance of key archaeological sites — including village sites, fortification sites and mortuary sites — that makes this work so pressing, says Parsley.

Many significant sites are extremely vulnerable to incidental damage and vandalism, and some have even been excavated and looted by treasure hunters.

“Since 2010 alone, eight of our burial boxes have been desecrated,” Hegus John Hackett said in a press release.

Now that the team has done its first preliminary reconnaissance, Parsley says, they’ll be “prioritizing which are most significant and vulnerable to recreational impacts.” The team will then return in the shoulder season to do detailed mapping and assessment work, including radiocarbon dating using samples of charcoal and faunal bone.

“You can’t protect or manage something if you don’t know where it is,” Parsley says.

Attending to the dead

As Parsley and I sit in the cabin of the boat, she pages through three binders of locations tagged with Borden numbers — a national system used to track archeological sites and artifacts in Canada. The Tyee has agreed not to reveal the exact locations of any of the sites we visit, in accordance with archeological guidelines and to prevent desecration and looting. But Parsley shows me a few archeological records for illustrative purposes. The previous archeologists, she says, estimated the length and width of the sites based on surface visual cues. A description from one example reads, “site has been badly damaged from past logging.”

Outside, in the distance, there are jagged mountains, some still covered in snow, which resemble serrated teeth. High tide lines are visible on the craggy shores. Some cliffs are steep and bare; others are more gentle, covered in salal and Douglas fir.

This project will span two years, including approximately 83 days of archeological assessment. A $500,000 investment from the Ministry of Tourism, Arts, Culture and Sport’s Destination Development Fund, with additional investment from the Tla’amin Nation, is making it possible.

In the first stage of the project, the team has found new culturally modified trees, new intertidal features such as canoe skids, clam gardens and wuχoθɛn, or fish traps, three possible new pictograph sites and 20 artifacts.

The prime object, though, is to find the most sensitive sites — in other words, mortuary sites — and in particular, those likely to be hardest hit by tourism.

Midway through the day, the team takes me to visit one of the four new mortuary sites they identified this spring.

We disembark and bushwhack through a tangle of blackberries and salal. Parsley explains the protocol for visiting the dead. In short, it’s important not to joke or laugh while we’re here. We should be quiet, sombre and respectful. Parsley crouches, and I sit next to her.

Parsley shines her headlamp into the grave; it takes a moment, but when my eyes adjust, I make out the the top of a skull. Parsley narrates what I’m seeing: there’s the cranium, and the maxilla, which still contains two upper incisors. The sutures in the cranium are fused, meaning the person buried here is an adult; Parsley can see the right mastoid, and its size indicates this person is probably a woman.

The two incisors we can see are burned, and the dentine is exposed, Parsley says, which means this person’s descendants visited them and fed their spirit by burning food.

“Just because you’re not here in your body anymore, your spirit is still around. And spirits will go hungry if they are not fed, and they are not cared for,” Tiy’ap thote Erik Blaney tells me later, on a call. “The dead are laid to rest. They are fed. And every year we feed their spirit.”

“When you disturb spirits,” Blaney says, “our people believe they can attach to you, and they will ride along with you.”

This site is both culturally significant and quite physically vulnerable, as it’s close to a place where someone could land their kayak or go exploring. Finding it “is a really good example in terms of the rationale behind the study,” Parsley says.

The burial could have taken place anywhere from 300 to 1,200 years ago, Parsley says. There are several different kinds of mortuary features in Desolation Sound and across Coast Salish territories, reflecting changing burial practices through time, she says. In the more ancient past, she says, underground interments were the norm, followed by in-ground shell midden inhumation and in-ground rock cairns. Around 1,200 years ago, people shifted to above-ground interments such as rock shelter burials to make it easier to regularly attend to the dead.

As we prepare to leave, Scott Galligos harvests two boughs of cedar to brush the surrounding area and offer blessings.

What was lost to contact with colonizers

After we’re back on the boat, and as I’m thinking about the person we’ve just visited, I ask what, in retrospect, is a naive question — is there cultural knowledge, or familial knowledge, that persists as to who is buried where?

“Contact obliterated cultural transmission of knowledge,” Parsley says. She reminds me that the Tla’min people, like other people in this area, lost 70 to 90 per cent of their populations within a five-to-seven-year span because of post-contact pandemics — before being subjected to further pressures of colonization, including residential schooling.

“Can you imagine all the things we couldn’t do if we lost 70 to 90 per cent of our population?” she asks. “What Oral Tradition does survive, we’re very blessed to have.”

“Where I learned all my knowledge was from Elder Norman Gallagher,” Blaney says.

Gallagher was raised in Bliss Landing, in Desolation Sound, and he was also head of the research department for Tla’amin’s treaty society. When Blaney was developing the Tla’amin Guardian Program, which is meant to ensure active and effective stewardship of lands and waters in Tla’amin territories, including cultural sites and artifacts, he went out into the sound with Gallagher, whose parents and grandparents raised him on the land. Gallagher shared what he knew with Blaney.

“We don’t know who they were, but we know typically which village site they were living at, and when they would have been buried in a certain place, or laid to rest in a certain place,” Blaney says.

Blaney points out that the province’s Cemetery and Funeral Services Act does not protect burial grounds dating prior to 1846. Instead, these sites receive weaker protections under the province’s Heritage Conservation Act.

“There’s a huge market for our artifacts, and even our burial remains,” Blaney says. “People have been stealing them for over 100 years, and putting them on their mantles, or selling our artifacts or our human remains on eBay.”

The province “dropped the ball” when it excluded these burial sites from the Cemetery and Funeral Services Act, Blaney says. The act should be amended to include burials before 1846, he adds — an amendment First Nations leaders have advocating since at least 2014.

“There’s areas within the Desolation Sound Marine Park where we’ve had to move trails and shut down trails, but people just don't understand, or don’t get the reasons why,” Blaney says.

“You get a lot of pushback. People will say, ‘I've been coming here for 35 years, and it’s my right to walk that trail,’ not realizing that there are human remains six centimetres under their feet when they’re walking certain parts of that trail.”

‘A proper plan in place to protect these sites’

Back on the water, Parsley asks Gerry Galligos to pilot the boat to an area that contains an important occupation site, where we’ll float offshore and eat lunch.

“This is Flea Village,” Parsley says, gesturing towards the shore.

She shares the story: in 1792, when Captain George Vancouver came on a voyage of “discovery” to this area, a small expedition consisting of Peter Puget and a crew of eight men were sent to take a closer look at areas of the shoreline that couldn’t be accessed using Vancouver’s larger ships, the HMS Discovery and HMS Chatham.

They arrived here in a cutter, Parsley says, and discovered a palisaded village they estimated could support 300 inhabitants. Finding no one, they snooped around — but soon discovered they were covered in fleas. Puget and his crew submerged themselves in the waters of the sound, Parsley says, but it didn’t quite do the trick. They had to boil their clothes to rid themselves of the fleas.

Flea Village was first recorded in the 1960s as an archeological site by Donald Mitchell, who did a superficial survey of artifacts, Parsley says.

When archeological work was done in the sound in the 1960s and ’70s, around the time of the founding of the marine park, they couldn’t locate this site with certainty, Parsley says.

To find it for this project, the group lined up old black and white photos with the shoreline, until they were sure they recognized it.

“The hair on the back of my neck stood up,” says Scott Galligos. He immediately felt they’d relocated the village Puget had visited. It also underscored for him the presence of his ancestors on this land. “The footprint is everywhere,” he says.

As we leave Flea Village to revisit a few other documented sites and scan to find new ones, Galligos pulls out his drum, and begins to play the tribal journey landing song. “I’m going to reclaim this area through song,” he says.

Galligos, who was one of the last groups of youth to be sent through St. Mary’s Mission school, says his participation in this project has been good medicine.

“I am standing in sites thinking that our ancestors stood here,” he says. “They’re the whole reason I’m standing here today.”

Alexis Rubletz, who grew up in the city and moved back to the area fairly recently — and also recently found out Scott Galligos and Gerry Galligos are cousins of hers — says visiting these ancestral sites, and being out on the water learning from Parsley and Scott Galligos, has been very personally meaningful.

“It’s so interesting to think about how we survived as people here,” she tells me. “Everything was readily available. Our ancestors were so self-sufficient.”

Blaney echoes this sentiment as he describes the evidence of Tla’amin people on the landscape throughout the nation’s territory. The tiskʷat village site, for example, continues south past Grief Point, all the way to Myrtle Rocks, he says.

“Any flat spot, any flat surface, any place with some running water, our people were living,” he says.

Researchers from Simon Fraser University have estimated that anywhere from 30,000 to 60,000 people lived in Tla’amin territory pre-1400s, pre-contact, Blaney says — more people than live in the qathet region now.

In 2021, t̓išosəm, a village site whose name translates to “milky white waters from herring spawn,” was dated to 10,000 years ago, making it one of the oldest known sites on the south coast.

When contact brought disease, Blaney says, it changed burial practices. Cremation was adopted over above-ground burials and tree burials. In some cases, such as at šɛʔaystən, or Emmonds Beach, for example, Blaney says, which was recently desecrated by bulldozers and graders, a couple hundred people who had gotten very ill were left there, and were not able to be attended to in the way they normally would have been.

“Places like Emmonds Beach are so sacred to us because a lot of the people there didn't get a proper burial and there are human remains all along the creek,” he says.

‘We didn’t treat it as a park’

In addition to amending the province’s cemetery act, Blaney, who initially helped develop the Indigenous Guardian program in partnership with BC Parks, would like to see a return to provincial natural resource officers being proactive in the territory, rather than reactive. This would mean patrolling sensitive areas regularly to make sure that people aren’t damaging them.

He’d also like to see Tla’amin guardians receive more authority for enforcement when they witness infractions taking place — right now, their role is to observe, record and report, he says.

“I'm at a point now where BC Parks should stop inviting people to our territory until they have a proper plan in place to protect these sites,” Blaney says. “Quit advertising to come here if you don't have the resources, and you don't have the capabilities, to protect our sites within your park boundaries.”

“We didn't treat it as a park,” Blaney says of Desolation Sound. “It wasn't a place that we just went and camped out and hung out at. That was our home. Those are our village sites. Those are where our people are buried.”

“It's still very important to us. And it is still our home. It is still a place that we cherish and go to. It's important for us to protect it.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: