They put Ray Haynes in jail at 84, and he was only shocked it didn’t happen sooner.

For decades, Haynes led British Columbia’s unions in the days when striking workers were routinely jailed. He spent a lifetime at picket lines and protests, masterminding some of the biggest job actions in British Columbian history.

But Haynes didn’t end up behind bars until 2012, when he joined environmental activists in White Rock protesting coal shipments. “When they tried to get me in the police car, they had a terrible time. My legs were falling apart and all that kind of stuff,” Haynes later joked. Every other protester sat on the station floor; Haynes got a chair.

Haynes would relay that story to friends with a smile and a wink.

But the message was clear: at every job action, every protest, Ray Haynes had always been willing to go to jail for his principles, even if he only had to do it once.

Haynes, the former secretary-general of the BC Federation of Labour and its oldest living officer, died earlier this week at the age of 94.

Haynes rose from the night shift on the sawmill floor to become one of the most influential union leaders in B.C. history.

Under his leadership, B.C.’s unions became more militant, more organized and more united. Haynes went toe-to-toe with the Social Credit government of the day, challenging employers’ use of court injunctions to quash job actions and jail union workers.

“He’s the best leader they’ve ever had,” said Harold Steves, a former Richmond city councillor and labour activist. “We’ve never seen anyone like him since.”

Later, he would become a failed resort owner, a lifelong activist, a thorn in the side of NDP premier Dave Barrett and an elder stateman to countless union leaders.

The son of a detective and a nurse, Haynes grew up in Vancouver’s Point Grey neighbourhood and got his first union job in 1948 at a sawmill on the banks of the Fraser River. “Right off the bat I could see the difference in working in a union plant,” he told the Vancouver Province in 1977.

He later took a job mixing tea at the Hudson’s Bay department store in Vancouver and helped organize that shop under the banner of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union.

He took the helm of the BC Federation of Labour on June 15, 1966, his birthday. It was a time of turmoil. Under the Social Credit government of the day, businesses could rely on court injunctions to quash job actions. “They could just phone some judge in the middle of the night who would roll out of bed,” said Joey Hartman, the chair of the BC Labour Heritage Centre.

That meant union members routinely went to jail. “It was a great art form in the BC Fed to avoid injunction servers, because you wouldn’t want to get the injunction served on you if you’re defying the courts,” said Ron Johnson. Johnson, a longtime NDP member, met Haynes while canvassing together for the 1969 election.

In those days, the federation was one of the most militant labour movements in Canada. Haynes was constantly in the news, often battling with then-premier W.A.C. Bennett. The federation twice seriously discussed a general strike.

“It was an all-out, brutal war,” former B.C. attorney general Colin Gabelmann said. At one point, the Social Credit party introduced a new law that gave the province unprecedented powers to arbitrate private and public labour disputes. When they tried to use that law to force the BC Building Trades back to work, Haynes told those unions to defy it.

“There was a tremendous amount of pressure for us to go back to work because of the fines,” said Bill Zander, the former head of the carpenters’ union and a friend of Haynes. “The RCMP raided 10 of our locals, took our documents and arrested us.”

But Haynes wouldn’t budge. “If there was any position being taken by the trade union movement, Ray was very determined that we should abide by it,” Zander said.

To his enemies — and he had many — Haynes was a menace. “He used to joke and imagine that these people who called him a ‘labour boss’ thought he had a big button on his shirt that said ‘General Strike,’ and he could just press the button,” Johnson said.

But his friends knew Haynes as different man. He was unwavering, but not unreasonable; principled, but polite. If a small union needed help, he wouldn’t hesitate to put the federation’s resources behind them. “Some of the labour leaders of those days were big and blustery with hammer and tong speeches,” said Jef Keighley, a friend of Haynes. “Ray was one of those guys who spoke softly, but carried a big stick.”

To Johnson, a young man at the time, Haynes was an icon. “He was the leader of working people in B.C., put simply,” Johnson said. “He was the glue for the labour movement that everyone could rally around.”

Haynes was firm with friends as well as foes. Keighley said one of Haynes’ great accomplishments was getting unions to pledge to respect each other’s picket lines — in essence, meaning a fight with one union meant a fight with all of them.

When some unions didn’t respect that rule, Keighley said, Haynes would be diplomatic. Then, if they didn’t relent, he worked to kick them out of the federation, even though it cost the organization money. “Ray took the position that the dues are important, but they’re not as important as the principal of respecting the picket line,” Keighley said.

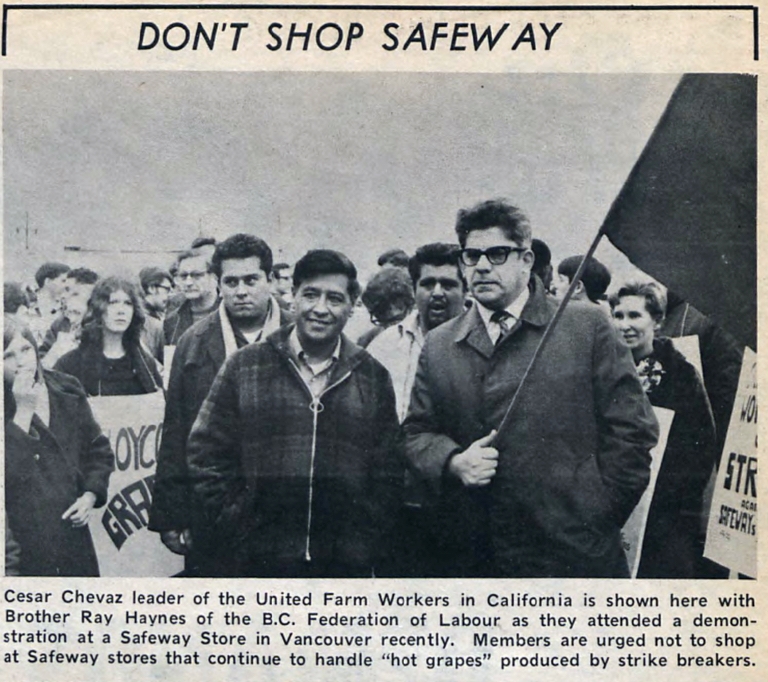

When the federation decided to support Cesar Chavez and the United Farmworkers in their boycott of California grapes in 1970, union members in B.C. didn’t just refuse to sell them. They refused to transport them at all, and even protested outside stores that sold the grapes.

It was not the only time Haynes would bring the federation into an international fight. Gabelmann, the former MLA, said Haynes viewed unions as a tool for social change. Under his leadership, the federation established committees for environmental protection and women’s equality. It opposed oil drilling in the Georgia Strait and the war in Vietnam. In 1971, for 30 minutes, workers across the province downed tools to protest American nuclear testing.

“He always, always, always saw the world from the point of view of the underdog, from the dispossessed, from the view of people whose life was tougher than his,” Gabelmann said.

Haynes wasn’t a gambler, but poker was his favourite hobby. He, Gabelmann, Zander and other union members would play games into the small hours of the morning. “There was almost always a poker game during federation conventions or during the two week-long labour schools, and many of the games would stretch through until 5 or 6 in the morning,” Gabelmann said. “And then people would go back and be bright and shiny for the convention receiving at 9 o’clock in the morning.”

Some players drank like fish and smoked like chimneys, but not Haynes. “It was diversionary. It enabled a kind of relaxation away from the rigours of tensions in labour relations, and the tensions within the labour movement for that matter,” Gabelmann said. He kept going to those games even in his older age.

His eldest daughter, Deborah Niewerth, said Haynes would stay with her and her husband whenever he was in the Lower Mainland to play. “We always joked it was like having a teenager because he would roll in at 1 or 2 in the morning,” Niewerth said.

One of Haynes’ great challenges came in 1972, when Dave Barrett’s NDP won power. Haynes, a former BC NDP president and longtime supporter, was elated. But he would have a contentious relationship with Barrett’s government.

Gabelmann, an MLA at the time, said Barrett wanted to distance the government from the labour movement; he saw it as a political incumbrance. Haynes and some MLAs, meanwhile, felt Barrett broke key commitments to union workers.

Haynes was critical of parts of the new Labour Code, for example, even if he agreed on the need for such a document. Steves, one of three NDP MLAs at the time who voted against that bill, said that brought him and Haynes into trouble. It also forged a friendship.

“It sort of brought us together,” Steves said.

Johnson said Barrett also didn’t uphold a promise he made to guarantee unfettered picketing rights for union workers. At one point, Haynes eyed running for the BC NDP in Vancouver, but backed out. “The tension of being in such significant conflict with your leader, if you’re a candidate, is too much,” Gabelmann said.

Haynes quit the top job at the federation in 1973. He told the media the job was responsible for the streaks of white and grey in his hair. “I’ve found each year taking as much out of me as two or three years in other jobs I have had,” he once told the Vancouver Sun.

Niewerth said her dad also wanted to spent more time with his kids. They would go on long road trips to Disneyland in California, where Haynes would sing all the way down — mostly Frank Sinatra, oldies and little made-up tunes.

Haynes bought a fishing resort on Quadra Island with his wife at the time. By most accounts he wasn’t good at it. Niewerth said it was a tough, seasonal gig. And her dad confessed his union sensibilities didn’t always jive with the bottom line. “I probably paid the highest wages on the island,” he told the Sun.

Haynes returned to union work. He worked at the BC Nurses’ Union, the BC Federation of Teachers and the Vancouver Municipal and Regional Employees Union, where he worked with Hartman.

This was a different era, the time of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, when unions across the world were losing members and influence. But Hartman said Haynes rejected the cynicism many labour unions felt. “He said ‘to hell with that,’” she recalls. Haynes often reminded his peers everything they did was for the workers they represented. He urged them to never settle for a moderate first contract and reminded them many workers had likely risked their careers to organize with the union. “They have expectations, they have fire in their belly, and you need to make that work,” Hartman remembers Haynes telling her.

Even after his retirement, Haynes kept busy. He built a miniature three-hole pitch-and-putt course at his home near Halfmoon Bay. He cooked fabulous meals, Hartman said, inspired by his mother’s Lebanese roots. And he kept playing poker with the old gang. When Johnson visited Haynes in the hospital, he said Haynes was anxious to get out in time for the February match. And Niewerth said her dad was always writing cards to friends for Christmas, a birthday or an anniversary.

In a statement, BC Federation of Labour president Sussanne Skidmore and secretary-treasurer Hermender Singh Kailey mourned Haynes’ passing.

“For seven decades, unions in B.C. have been able to count on Ray Haynes’ passion, leadership and courage — not to mention his warmth and humour. Many of us are hurting at the thought he won’t be here anymore to give us his advice and, at times, gentle prodding,” the two wrote in a joint statement.

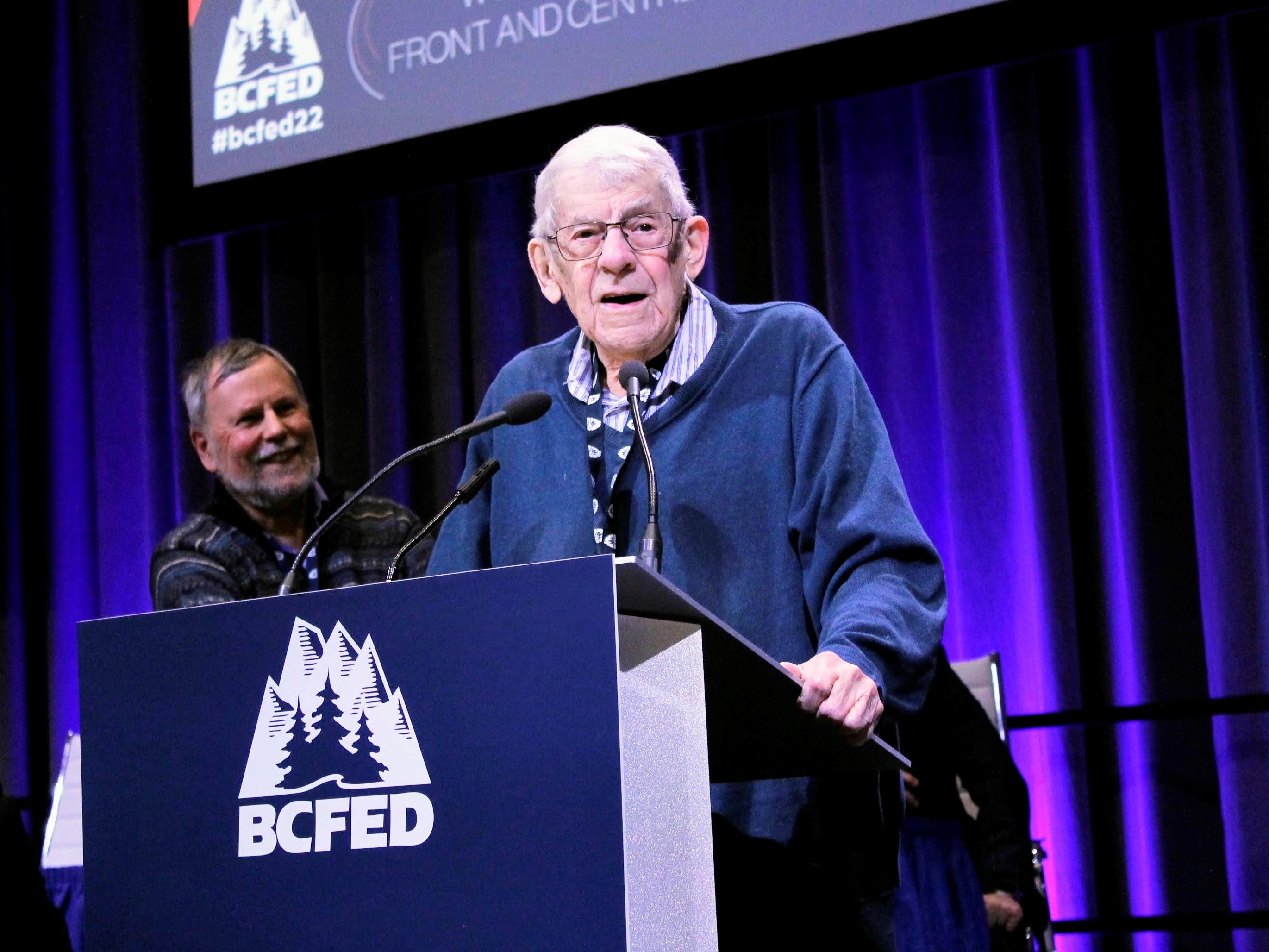

Haynes addressed the federation’s convention for the last time in November. At 94, he still insisted on driving right to the front of the Pan Pacific hotel.

“He said ‘if I don’t have to speak, I’ll come,’” Johnson said. But then hundreds of union members jumped to their feet to applaud him, and he conceded he had no choice. He spoke about the California grape boycott, his poker games and that day in White Rock in 2012, when he finally went to jail for what he believed. “I got a couple more years behind me,” he told them then. “So I’ll try and be with you.”

Ray Haynes died on Monday.

He leaves behind a wife, his brother, three children and a province he changed. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: