In March 2021, nearly three decades of living in her Calgary rental unit came to an abrupt end for Kate Lewis when she and other residents of Bridgeland Place received eviction notices.

Calgary Housing Co., a subsidiary of the City of Calgary in charge of managing the city’s affordable housing stock, promised tenants “a smooth transition to alternative homes.” But amid a landscape of burgeoning gentrification in Bridgeland-Riverside, anxiety ran high.

“The stress has been horrible,” Lewis said, pointing to the uncertainty of the relocation timeline — which is gradually taking place over 21 months.

When Lewis moved to Bridgeland-Riverside, an inner-city neighbourhood in Calgary’s northeast, it used to house the city’s working class.

It was once an enclave of German and Italian immigrants. Just over a decade ago, the earnings of most households were below the city’s median income of $83,220 (before taxes).

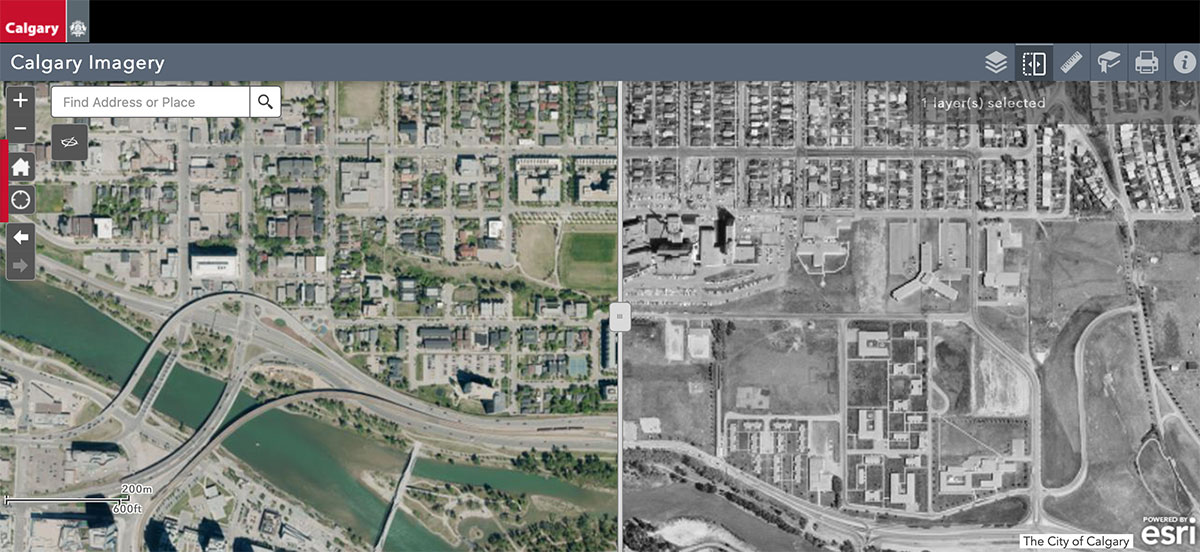

But since the city began the redevelopment of its former Calgary General Hospital lands in the early aughts, the neighbourhood’s reputation has changed. More than 1,500 homes have since been built in the area now branded as “the Bridges.”

Bridgeland-Riverside is often touted as an example of a successful revitalization strategy that’s attracting much-needed families back to the city’s core. Master-planned and strategically located within walking distance to downtown and a light rail station, the development leverages the neighbourhood’s character and a hilly topography that allows for panoramic views of the urban landscape.

The red brick façades of commercial buildings and turn-of-the-century homes wane among the proliferation of mid-rise buildings clad in glossy, contemporary finishes that, blending the old and the new, accommodate both residential and retail spaces.

Hip restaurants, pizza joints and ice cream parlours line First Avenue Northeast, the neighbourhood’s main drag, attracting patrons from all over the city. Visitors can enjoy a $5.50 scoop of salted caramel ice cream at Murdoch Park.

Bridgeland-Riverside continues to have a high concentration of low-income residents — 10 per cent of Calgary’s non-market housing stock is located there — but that’s changing.

Affordable units, more likely to exist in older buildings, were already becoming less available in the mid-2000s, according to data on the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. website. Non-market units were at risk too.

Then, in March 2021, the City of Calgary announced it would be closing Bridgeland Place, one of the largest city-owned buildings in Calgary that represents almost a tenth of the city-owned stock.

In Calgary, the renaissance of inner-city neighbourhoods is increasingly displacing lower-income residents to areas further away from the centre, in a process similar to that experienced in Toronto and Vancouver.

Calgary not only has the lowest rate of non-market units per 500 households in Canada, according to recent data compiled by UBC’s Housing Assessment Resource Tools project, there is also a deficit of 58,630 homes in Calgary renting for less than $2,000 per month.

Bridgeland Place’s 210 units were built by the provincial government in 1971 and since then have provided stable housing to many generations of low-income Calgarians who rely on the availability of deeply subsidized, rent-geared-to-income housing to stay out of homelessness.

In typical 1960s fashion, the brutalist façade of Bridgeland Place stretches its tan brick cladding along the length of 18 floors. Inside, modest white walls bound the long empty hallways leading to the one- and two-bedroom units that, until last year, accommodated more than 300 residents.

On the top floor, a common area unveils an expansive view of the city — an unexpected treat for an unassuming building. Once, tenants could also enjoy this view from a rooftop patio, but access to that outdoor space was eventually restricted by the building’s management.

While signs of wear and tear are evident throughout the building, only a few stains on the slate-coloured carpet hint at the people who used to call Bridgeland Place home. Behind the gleaming aluminum panels that clad the elevator’s walls, myriad issues inherent to a structure of that era are concealed.

According to documents obtained by The Tyee via Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy legislation, the City of Calgary conducted a lifecycle assessment in 2017 that described several of the building’s systems — heating and ventilation, water and plumbing, as well as the elevators — as in need of significant upgrades and repairs.

The cost could be upwards of $15 million over the next decade — a significant expense considering the building’s assessed value is roughly $1.5 million.

Despite these ongoing challenges, the closure of Bridgeland Place came as a surprise to its tenants.

Having 21 months to find alternative accommodation may sound like plenty of time — the eviction deadline is Dec. 31, 2022 — but in a municipality with a non-market shortfall of 43,000 units, multiple challenges would inevitably arise.

While families in need of larger homes were among the first ones to be successfully relocated, singles requiring one-bedroom apartments have had to wait longer, as the availability of this type of unit is limited in Calgary.

Even though Lewis had filed a relocation request in 2020, prior to the closure notice, it wasn’t until late October 2022 that Calgary Housing Co. was finally able to offer a suitable unit at an alternative location. She was given one month to move out of Bridgeland Place.

Lewis said the uncertainty around her living situation has been extremely distressing.

She was lucky to be offered a unit at a location of her choosing. In late November, she’ll be moving to Southview, in Calgary’s southeast, to live closer to her parents.

“It’s the only place in that area that has one-bedrooms,” she said.

As the eviction deadline looms, tenants who pass on the housing alternatives offered by Calgary Housing Co. risk losing their space in deeply subsidized housing and will be left on their own to find a place to live.

Although the future of Bridgeland Place won’t be determined until next year, it’s not hard to imagine what could come next, given its desirable location.

Last year, Calgary’s city council directed its staff to ensure that the future of Bridgeland Place aligned with local planning documents, and that the lost affordable units are replaced at a location where “the overall benefit to Calgarians is greater.”

The city administration soon produced a confidential report that resulted in the hiring of a third-party consultant to conduct a feasibility assessment and produce a range of future alternatives for the site.

The consultant’s work has not concluded, but proposals could include renovating the existing building, or the building’s demolition and subsequent redevelopment.

Just a handful of blocks east of Bridgeland Place, 14 hectares of Bridgeland-Riverside have already been “revitalized” as part of the Bridges’ master plan. The parcel of land the subsidized housing sits on — about one hectare — is roughly the same size as the now built-out section of the Bridges’ third and last phase.

This redeveloped one-hectare site includes the Dominion, a luxury rental building with an assessed value of $59,490,000, and Radius, a high-end condo being marketed to investors — both of which have been recently erected.

The Bridges, while successful in raising land values in the neighbourhood, could negatively affect the preservation of Bridgeland Place. Calgary Housing Co. could capitalize on the revenue potential the site represents and build more affordable units elsewhere, rather than incurring on the expense of renovating an aging building.

“When you have a very valuable asset but it’s a crappy building, a rational landowner would in fact redevelop that property… [and] optimize the use of that asset,” said Steve Pomeroy, an independent consultant and research fellow at Carleton’s Centre for Urban Research and Education.

Pomeroy said municipalities can use the revenue produced by the sale of publicly owned properties at desirable locations to build more affordable housing elsewhere.

“[Calgary Housing Co.] can utilize their assets to generate significant surpluses, and use the redevelopment proceeds to reinvest,” he said. “Because the province is not giving them any money, they have to figure out how to generate their own sources of revenue on this very attractive, very well-located property.”

Gentrification, a process wherein low-income residents are displaced by more affluent individuals, is one of the greatest challenges cities globally face today. And despite its relative affordability, Calgary is no exception.

Gentrification also increases land values, an incentive for governments to sell their assets in gentrifying areas for a profit.

A recent report authored by Pomeroy found that, in the last decade, Calgary lost more than 4,000 market rental units priced below a monthly rate of $750. In the meantime, over 20,000 units renting for $2,000 or more per month were created.

Not all of these losses and gains can be attributed to demolition and construction. The renovation and upgrading of formerly affordable units, to cater to a more affluent market, also plays a key role in affecting these numbers.

But the fate of Bridgeland Place is not inescapable.

As Leslie Kern put it in her most recent book, Gentrification Is Inevitable and Other Lies, “the story of gentrification being inevitable ignores the fact that governments are not powerless in the face of gentrification. Their refusal to intervene has been a choice.”

Indeed, according to Pomeroy, land ownership gives cities an upper hand when it comes to enacting policies that help mitigate gentrification, such as inclusionary zoning, rental replacement bylaws, or leasing lands to private developers on the condition of including non-market housing in new developments.

“Owning property gives you control,” he said. “Ideally, we want to have a blend of moderate, low-income housing in every neighbourhood.”

But in Calgary, half of neighbourhoods lack any affordable housing, and much of the new housing built in burgeoning neighbourhoods isn’t within reach for people of all incomes, exacerbating gentrification and displacement.

In the Dominion, the monthly rent for a one-bedroom unit starts at $1,900. By contrast, the average rent for a similar unit in Bridgeland-Riverside is $1,103.

Tim Ward, manager of housing solutions at the City of Calgary, said ensuring the preservation of affordable housing is a priority for the city. However, he told The Tyee in an interview, there is no commitment to replacing the units lost when a property is no longer viable, or to ensuring new units are created in the same neighbourhood where they have been lost. Instead, decisions are made in a case-by-case basis.

“It’s just a case of always monitoring the data and evaluating and weighing up the options,” Ward said. “So that you look at a situation on a specific property and then that guides a decision whether you renovate, redevelop or something like that… it’s about a constant process of understanding what we need to do on a building-by-building basis.”

The effects of gentrification in Bridgeland-Riverside will ultimately depend on what the city chooses to do.

“If they do intend to redevelop [Bridgeland Place] and bring back 200 units of moderately affordable housing, there’s no net loss,” Pomeroy said. “[But] if they take the proceeds somewhere else, you do have a gentrification issue in that neighbourhood.”

Having lived in Bridgeland-Riverside for close to three decades, Lewis is happy to be leaving because she no longer feels welcome in the neighbourhood.

“When I moved here it was a very nice place to live,” she said, noting that as new people moved to the area in recent years, negative perceptions towards the tenants of Bridgeland Place increased.

“I’m sure lots of people in the community think that there’s just a bunch of bums living here.”

As the city’s efforts to bring life back to Bridgeland have come to fruition, the affordable cafés, bakeries and shops Lewis used to frequent have been replaced by a new wave of businesses that cater to a more affluent demographic.

“You could go to the bakery and get a decent loaf of bread for cheap,” Lewis said. “Now the 7-Eleven is the cheapest place around here.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Housing, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: