[Editor’s note: This story contains information related to sexual harassment and the unresolved cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. It may be triggering to some readers.]

Photos of Traci Genereaux as a kid show a typical childhood. Her grandmother, Darcy Martin, has a photo album on her computer that contains hundreds — there’s a photo of Genereaux climbing a tree and standing beside a horse, one of her holding her tongue out to catch falling snowflakes, another of her dressed up in a costume and a bright-coloured wig. There’s one that Martin had printed and framed of Genereaux as a young teenager with long, curled auburn hair, wearing thick blue eyeliner and a red plaid shirt. She has her hands on her hips and she’s smiling, staring straight into the camera.

Speaking over the phone from her hometown of Vernon, B.C., Martin describes a granddaughter who was feisty and full of life.

“There was nothing that she was afraid to try,” she says. “If you asked her to do something you thought she might be afraid of, she’s going to show you she’s not afraid.”

Martin looks at the photographs on birthdays and anniversaries to remind herself of happy memories. She also shares a few on Facebook each year on the day her granddaughter’s body was discovered.

Genereaux was last seen in May 2017 when she was 18 years old. It was six months later, on Oct. 21, 2017, when her remains were discovered on a rural farm in the Salmon River Valley by the Vernon RCMP. It’s unclear when, exactly, she died.

“She did have some struggles with drug use that she was trying to overcome, and I believe that she was getting there with it,” Martin says. “She was moving in the right direction, [and] was hopefully going to beat it and carry on with her life.”

Photographs of Genereaux have now come to represent the call for attention to the Stolen Sisters campaign in the North Okanagan. They’ve been glued to countless posters at rallies over the past five years.

How her remains ended up on this remote farm remains a mystery. But the property is known in the area: it’s where Curtis Sagmoen, a man notorious for crimes of violence towards women, lives with his parents.

Sagmoen has a string of assault charges.

In 2013 he pled guilty to assaulting a woman with a hammer in Maple Ridge, B.C. In December 2019 he was found guilty of disguising himself and threatening a sex worker; she testified in court that she had arranged to meet Sagmoen at his property and when she arrived, he leapt from the bushes, terrifying her with a shotgun. For that, Sagmoen was sentenced to 36 months of probation.

In another incident he pled guilty to using a spike belt to deflate the tires of a woman’s vehicle on the dirt road by his property; he was given an absolute discharge. And in 2020, he was found guilty of hitting a woman with an ATV so hard that she flipped over the machine and landed on the ground. He was sentenced to five months of time already served in jail, a three-year term of probation and a long list of conditions — on top of being given a 10-year weapons ban, he was ordered not to have any contact with any sex worker, escort or anyone offering paid dating or companion services.

Police have called Genereaux’s death suspicious but despite a search of the Sagmoen property that took three long days, with machines brought in to dig up the earth, no one has been charged in connection with her death.

And while the news shocked this usually sleepy rural region, there is a bigger story: Genereaux is just one of five women who, in a span of about 18 months from 2016 to 2017, went missing from the Salmon River Valley and nearby small towns. The body of Ashley Simpson was found in November 2021 and her boyfriend at the time, Derek Favel, has since been charged with second-degree murder. They had been living together on Yankee Flats Road in the same valley where Genereaux’s remains were found. Deanna Wertz, Caitlin Potts and Nicole Bell also went missing from the area between 2016 and 2017.

Twice in the past few years, Vernon RCMP have issued public warnings to sex workers. They warned any person involved in the sex trade “not to respond to any requests for their services, and not engage in any activity in the Salmon River Road area.” In a statement to The Tyee, RCMP said investigations into the disappearances of the five women “remained under active investigation.”

Police will not comment on whether Sagmoen is a suspect in any of the disappearances. In a statement, Vernon RCMP told The Tyee that they would only confirm the identity of the “individual(s) involved” “in the event that an investigation results in the laying of criminal charges.” The lack of specific response raises concerns among some, including Lorimer Shenher, a former detective with the Vancouver Police Department who has been outspokenly critical of how police limit information in missing persons investigations.

As frustration that no one has been charged with Genereaux’s death grows in the community, protesters regularly gather to demand action from police, from the courts and for witnesses to come forward. The campaigns in the North Okanagan are mostly led by Indigenous women who have taken up the mantle to seek justice for the missing — whether they’re Indigenous or not.

‘No charges. No justice’

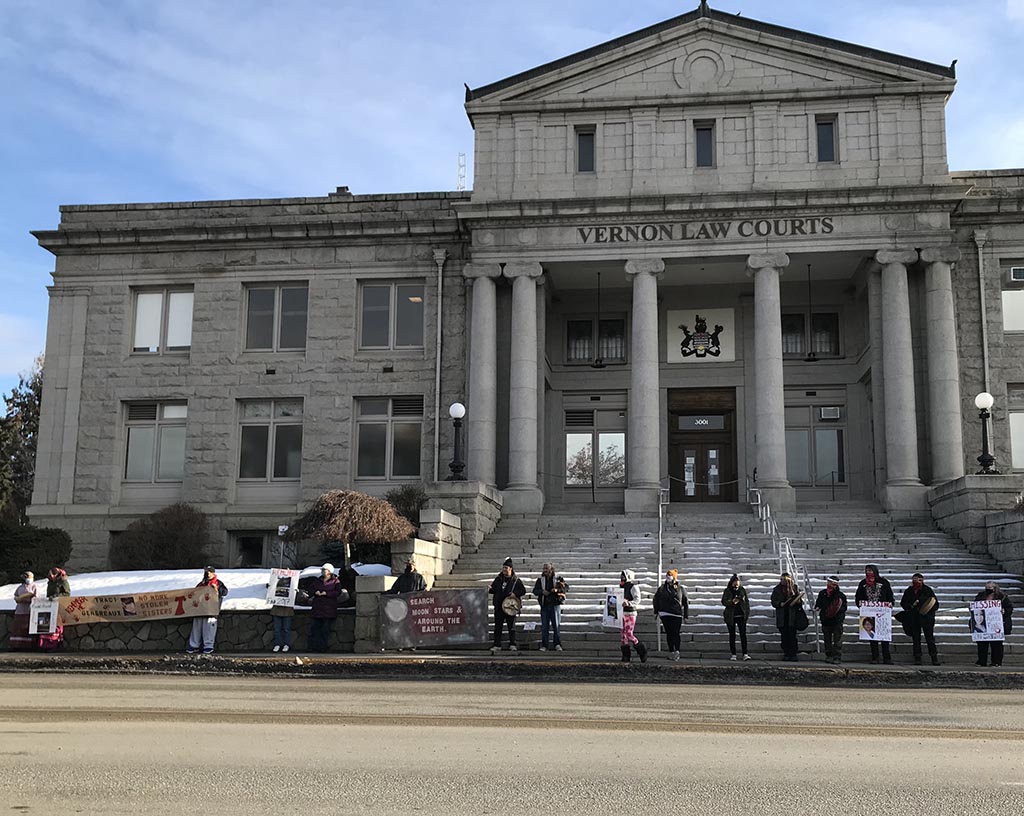

On a typically cold and dreary mid-January day in 2021, a group of protesters gathered at the Vernon Courthouse where Curtis Sagmoen was meant to appear for an arraignment hearing on a charge for allegedly assaulting a female peace officer who was conducting a search of the family property.

While Sagmoen did not show up and the charge was later stayed, dozens of youth, men and women from the community did.

Among them was a woman who grew up with Traci Genereaux who wished to remain anonymous for her own personal safety. She was bundled up in a duffel coat to brace herself from the bitter cold. Her mix of anger and sorrow was close to the surface as she explained why she was there.

“Eighteen-year-old girl was found buried. No charges. Nothing, no justice. She was a kid. She was deserving of a good life,” she said, shaking her head. “How she ended up, I don’t want that to be her legacy. And I feel like people are forgetting about it.”

“There is a feeling that something is going on amongst these women that are missing in the North Okanagan,” says Elaina Young. She and her teenage daughter Fiona live in the region. They took the day off to stand outside the courthouse, pacing up and down the sidewalk and waving their posters to keep warm.

Sex workers need more protection, Fiona Young said. Too often, she added, the media dehumanizes missing women who engaged in sex work before their disappearances.

“We’re here to show that this matters and it needs to be addressed and taken more seriously,” she said. “It makes me sad that we’re only paying attention to this because they found Traci’s remains.”

“Do they have to be white to matter? It doesn’t matter if they were sex workers or lived on the street or were homeless. They are people, they have family, and they matter,” Elaina Young added.

“It’s heavy, the weight of the responsibility,” said Palwícyaʔ, a Sylix and Secwepemc woman and one of the organizers of the January protest who goes by her traditional name for fear of being identified. For similar reasons, Palwícyaʔ wears a maroon-coloured floral scarf to cover her hair and a protective red face mask while protesting. “There is a very hopeless feeling in all of this. There’s no answers and it’s been years. There’s so much evidence brought forward that you think would provide something and it doesn’t.”

“It can come to a point where some of our women that come to these rallies or help lead them, they end up stepping down for a bit because of the amount of self-care you need to continue these things going,” she said.

And yet to this day, several times a year, the protesters continue to peacefully demonstrate. They light sacred fires, organize walks and marches, tack up missing person signs and hold candlelight vigils. Any time charges are laid against Sagmoen, or in any case related to the missing women, they buy gas cards so that family members can attend court hearings, then sit in the courthouse and listen to excruciatingly detailed accounts of assault, murder and rape.

They do all this for the families “because they need our strength,” said Palwícyaʔ. “Under no circumstances should the families be the only ones fighting this fight.”

‘He looked at me with a disgusted look, a smirk’

In many ways, the Salmon River Valley is the perfect place to hold secrets.

It’s a wildly beautiful landscape with meandering creeks and rivers crossing through tall stands of lodgepole pine, Douglas fir and trembling aspen. It’s quiet and secluded, the shallow slopes shape the valley in an isolating trench and the south ridge keeps the afternoon sun low in winter. The broad swath of land at the valley bottom is dotted with acreages and farms all connected by an entangled network of narrow roads. Many of the properties sit at the end of long, private driveways.

Priscilla Potts’ daughter Caitlin Potts, a member of the Samson Cree Nation, was last seen in the nearby small town of Enderby on Feb. 22, 2016, more than six years ago. She was 27 years old.

Priscilla still stays up late into the night, waiting for Caitlin to come home. Sitting in her darkened living room, she strains to hear sounds of her daughter pulling up in a car outside. She imagines that her daughter finally broke up with her on-again, off-again abusive boyfriend, that Caitlin is ready to come back home and start her life over.

Jason Hnatiuk, who has publicly denied being Caitlin’s boyfriend, was found guilty of assaulting her with a weapon in 2014. Priscilla watched surveillance footage of the assault, which was played in court a few years after the assault and after Caitlin’s disappearance.

Caitlin grew up in Alberta but had left the province to head west and ended up in Enderby, B.C., a few months before she disappeared. She was bubbly, smart and stubborn, Priscilla says. “But she seemed to always fall off the path and you know, stayed stuck out there I guess.”

For that, Priscilla faces a life sentence of regret that if only she’d been a “better mother,” her daughter may have gotten on a different path. Her daughter endured a lot of challenges growing up, she says, including that she was in foster care until she was 11 years old. Priscilla says she now lives for Caitlin’s memory, trying to be a better version of herself in her daughter’s honour “so that at least her death meant something.”

Priscilla Potts shares concerns about the RCMP’s approach to investigating the murders and disappearances of women in the area.

Her first and only RCMP interview about Caitlin’s disappearance with the RCMP did not go well, she says. She recalls sobbing inconsolably, struggling to put simple words together. In her grief, she kept repeating the same words to police, urging them to investigate her daughter’s boyfriend as a suspect.

She was crying and rocking, her heads in her hands, when she looked up towards the officers.

“I’m not sure which [officer] it was, but he looked at me with a disgusted look, a smirk,” she said.

When Potts raised it with the officer, he denied giving her a look or being in any way rude, but ever since, she’ll have nothing to do with the police. “What have they given me to trust them with? Not my daughter’s case, anyways. That’s what they’ve shown me,” she says.

Instead, to try to help move the case forward, a friend of Caitlin’s has launched a fundraiser campaign to hire a private investigator.

‘Our love is endless’

An hour into the winter protest outside the courthouse, a family of three generations exits a van and unfurls a large cloth banner that looks like a piece of art. It reads: “search moon, stars & around the earth.”

Miranda Dick is a Secwépmec matriarch and a stalwart supporter at gatherings concerning missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Onto the banner, she’s stencilled a brilliant white full moon and stars with blurred edges over a tie-dyed background that looks like a mottled universe. She arrived late — with her father and son by her side — because she worked through the night so she could give the banner to Traci Genereaux’s family.

“We have a saying that our love is endless, that we’d go to the moon and stars and around our world, that’s how much we love our children,” explained Dick.

“I won’t give up on these women, the ones who are both native and non-native, that are still missing,” she said. “In our Secwépmec way, we teach our children that if you are ever lost, to reconfigure yourself to the North Star to come home, it will declinate you.”

Dick sat through months of testimony during the trial of serial killer Robert Pickton in Vancouver. She has spearheaded searches for the missing across the province, travelled up and down the Highway of Tears in northern B.C. and now in her own nation, the Neskonlith Indian Band in Chase, B.C., she’s trying to bring attention to the missing and murdered women of the North Okanagan.

Dick, like Priscilla Potts, and other family members of the missing and murdered, is critical of the RCMP’s response.

A common concern is that the RCMP have not been adequately informing the family members of any updates in the investigations.

Critics and family members also allege that the RCMP has overlooked key pieces of evidence. For example, about a month after Ashley Simpson was reported missing, a hiker discovered some scattered clothing and belongings on a forest service road close to where Simpson was living that were later identified as Simpson’s. The woman who made the discovery left the items in place and notified the RCMP. Weeks later, when the hiker, who wishes to remain anonymous, revisited the site, she said the belongings were still there, sparking outrage on social media that police weren’t promptly following up on tips.

There are also widespread allegations of systemic racism that many believe tarnish missing women investigations to the point of being irreparably flawed.

Vernon RCMP denied The Tyee’s requests for interviews about any of the missing women’s cases. Instead, Staff Sgt. Janelle Shoihet offered a written statement.

“The disappearance of Deanna Wertz, Caitlin Potts, Nicole Bell and Traci Genereaux remain under active investigation and investigators will continue to meet regularly and share information,” the statement read in part. “We must refrain from providing specific information, so as not to compromise the integrity of any of these cases.”

Shoiet added that the investigation into the suspicious death of Traci Genereaux “remains active and ongoing and a priority for the team of investigators.”

In an updated statement made to The Tyee on Aug. 17, a new media liaison officer added, “It is important to note that any information provided and disclosed during an active investigation has a potential to positively or negatively impact the ongoing efforts to advance it.”

One person with intimate knowledge of how these kinds of cases are investigated is Lorimer Shenher, the former head of the missing persons unit of the Vancouver Police Department. He was at the centre of the investigation into serial killer Robert Pickton, who is currently serving a life sentence after being convicted of killing six women from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside — though he is suspected of killing dozens more.

Shenher wrote a book, called That Lonely Section of Hell: The Botched Investigation of a Serial Killer Who Almost Got Away, about the failures that hampered the Pickton investigation. He has been acutely critical of how missing women cases are handled, including the cases in the North Okanagan.

“[The RCMP] don’t seem sophisticated enough to discern what they can tell [the media] and what they shouldn’t,” he adds. Shenher wants to know what investigative steps the RCMP have undertaken to rule Curtis Sagmoen out as a suspect, whether major crime is involved and whether any of the cases have been elevated to the provincial homicide level and he doesn’t believe police would be in any legal jeopardy by answering.

“If they can’t tell you, it’s very problematic,” Shenher says. “It makes me suspect that RCMP are not actively investigating.”

“It’s unfortunate. The protests, the calls from the Indigenous community, [RCMP] will dismiss that. They’ll say it’s the haters. But to me, having five women missing in a small geographic area is 100 per cent a concern. It’s statistically an anomaly.” Shenher draws parallels with what’s happening in the North Okanagan to the Pickton case. There’s the demographic of women being affected — whether it’s the elements of poverty, marginalization, sex work or drug use. There’s a large rural property at the centre of the investigation; a character who, among sex workers, is known as a bad date; there’s the suggestion of police inactivity; and there’s fear in the community.

“I find it just so disheartening,” Shenher says. “[The Pickton investigation] seemed like the first case of its kind in Canada because it was such a large scope. We made the mistakes we made; but I never thought that other jurisdictions across Canada would continue to do the exact same things wrong that we did wrong, five, 10, 20 years later.”

“Where I really get frustrated is where we repeat the same mistakes without benefiting from the same experience,” he says.

‘We’re going to give voices to these women’

Seeing pictures of Traci in the news, or on the TV, still chokes Darcy Martin up. To return to better memories, she looks at the photos she has stored on her computer.

A couple of years ago, she also started a fundraiser, called Traci’s Gift, that compiles Christmas wish lists from families in need in her hometown of Vernon, B.C. To fulfil them, she collects money from the community by knocking on doors. “If [Traci] was still with us at Christmas time, this is something she would have loved to do. She had such a big heart and she loved helping people,” Martin said.

“That helped with the healing process a little bit,” she said.

Still, Martin holds out for answers and justice. She wants whoever was responsible for her granddaughter’s death to be held accountable.

This is what protesters are aiming for, too. In January 2021, once the group outside the Vernon courthouse got word that the day’s bail hearing had been further postponed, a number of protesters packed into trucks and drove the 30-minute distance to the Sagmoen farm.

“We don’t know that Curtis Sagmoen is involved with every woman that we speak for, but what we’re doing is bringing light to a bigger issue here. We’re not going to let this slide by silently,” said Palwícyaʔ. “We’re going to be loud and we’re going to give voices to these women so they know that even if they can’t speak for themselves, we’ll speak for them.”

The trucks pulled up on the edge of a gravel road that winds through the Salmon River Valley and the protesters quickly reassembled. Some of them wore ribbon skirts that waved like prayer flags against the piles of dirty snow.

“We want justice! We want answers!” they chanted. They took turns singing a Secwépmec Honour Song in strong, sure voices that boomed across the valley.

“Traci deserves answers!” Palwícyaʔ yelled through a megaphone.

The valley echoed back a deep silence, the stillness on the land stirred by a lone horse fenced up on the sprawling 27-acre farm below.

Undeterred by the emptiness of the valley and shuffling their boots in the hard packed mud and snow, the group broke into the Women’s Warrior Song, singing for Traci Genereaux and for all the women that have gone missing in this valley.

Above the Sagmoen farm, on the edge of the winding gravel road, someone has tacked a bright red dress to a telephone post — a reminder that Genereaux’s remains were found here and that the case remains open almost five years later, that so many questions have been left unanswered.

The group chanted a chorus with their drumsticks held up to the sky: “Caitlin deserves answers! Ashley deserves answers! Deanna deserves answers! Nicole deserves answers! Traci deserves answers!”

The tension broke when Palwícyaʔ shouted, “We’ll be back, you asshole!” which was followed by a roar of unexpected laughter. And then again in unspoken unison, they stopped for a minute of silence. A dog barked off in the distance; the trees creaked in the cold wind. There was almost a sense of peace as the memories of the missing, in that moment, were kept alive. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Gender + Sexuality

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: